RACHEL GINSBERG

Rachel Ginsberg is a multidisciplinary strategist and a member of the Columbia University School of the Arts Digital Storytelling Lab. She is also the creative strategist and experience designer for the interactive artificial intelligence installation Frankenstein AI. In this interview, she talks about the current anxieties over AI and the importance of developing technology using creative story-driven approaches.

Interview by Tyler Nesler

You have a professional background in brand and marketing strategy. How did this work bring you to your current position with Columbia University's Digital Storytelling Lab? How has it informed or influenced your approach to developing strategic directions between digital storytellers and an audience?

Indeed I do! It’s funny how often the two intersect. I mean, if we’re doing it right, marketing is entirely about finding and connecting an audience with the right message to influence some kind of outcome. Storytelling is the same, fundamentally. For an organization like the Digital Storytelling Lab, we also have outcomes we’re working towards. They’re just different.

At the Lab our mission is to explore forms and functions of storytelling. When we talk about forms, we’re talking about exactly what it sounds like. What forms will stories take into the future? How will people interact with them? When we explore future functions of storytelling, we’re interested in discovering how we can use stories in different ways for different purposes. So, thinking about outcomes for DSL is really more in line with questions about function than form. Like, how can we push the function of stories to shift culture, or create understanding, bring about healing or provoke action? These are the kinds of things we want to understand. In the case of Frankenstein AI, we use participatory storytelling as a device to create emotional stakes between the audience and the AI character to provoke thought and discussion.

How did you come to be involved as the creative strategist and experience designer for the Frankenstein AI project? What has "experience designing" entailed for you with this project?

I joined DSL about halfway through 2016, when Frankenstein AI was just an idea. As we began to initiate the project in spring of 2017, I worked with Lance Weiler and Nick Fortugno to design the prototype we launched in our monthly meetup and at South by Southwest. The output and learnings from that initial prototype ultimately formed the backbone of our first public installation built for the Sundance Film Festival’s New Frontier section in 2018. Broadly speaking, it’s a pretty fluid collaboration, so we all take responsibility for many different kinds of activities.

My role as a strategist and experience designer on Frankenstein AI is primarily focused on making sure that every aspect of the design of the experience contributes to addressing the big questions at the heart of the work: what is our relationship with artificial intelligence today, and what do we want it to be into the future? In terms of activities on the project itself, I do a lot of writing in and around the work, from scripting characters inside the experiences to creating materials that share our process with potential partners and collaborators of all kinds. But in terms of big decisions about the work, Lance, Nick and I work very collaboratively. We’re all responsible for our own pieces of the project, but when it comes to things like the narrative arc and aesthetic goal, we make those decisions together as a collective.

Frankenstein AI is a very unique combination of immersive theatre and interactive technology. Since storytelling is such a universally important and distinct aspect of human nature and culture, do you think this sort of creative and fluid approach to developing machine intelligence is a major key to ultimately creating more humanized or compassionate forms of AI?

Absolutely 100% yes. I believe that creative story-driven approaches are essential to creating technology that serves humans and not that which drives us to behave a certain way because of capitalism. We are only just now starting to take stock of the ways in which technologies and interfaces are designing human behaviors. Think about dating, for example. Online dating has provided all kinds of interesting opportunities to connect with people who we wouldn’t otherwise meet. But it’s also changed our approach to and perceptions of dating — given us an excuse to put less effort into making connections in the physical world. There’s nothing specifically wrong with that, but it is changing us rapidly in ways we can’t predict.

Stories give us a way to explore alternate realities, present, past and future. They’re our best chance at expanding our understanding of the possible — giving us the opportunity to imagine beyond the mostly dystopian narratives that are currently dominating the conversation around tech. AI is the technology that simultaneously triggers our greatest fears, but also inspires exciting visions of the future. Telling stories about it, with it, and around it will allow us to prototype and explore possible futures wherein AI is pervasive, because it will be.

In Mary Shelley's novel, Victor Frankenstein's creation is very angry and confused and revengeful. Since the novel's narrative was used as a foundation for the project's AI, the program started off at a baseline of anger, but how quickly did it move away from that baseline once enough varied emotional inputs were entered from the project's participants? How are the program's emotional transformations measured or tracked?

The emotions are technically measurable, but the way we really knew was based on the emotional states it displayed while interacting with people — as the festival progressed, we saw much more of a range.

The Frankenstein AI project was designed not only to create a conversation between the participants and the AI, but also to join strangers together in order to help the program process human emotion through machine intelligence. What's particularly interesting about this to me is that it brings people together face-to-face in the service of technology, which is wonderful and ironic considering that so many of us interact digitally now more regularly than we do in person. What do you think the key advantages are for Frankenstein AI to process information gathered between two people interacting face-to-face, as opposed to the project being set up with only online interactions?

I think what’s interesting about your question is that it’s not entirely “in the service of technology” that we’re bringing people together face to face. I mean, yes, one major goal of the project is to train an AI with a data corpus drawn from human interactions. We’re asking them to participate in those interactions so that we can put together the corpus. But the hope is to use the process of surfacing human emotional data to train to the AI as a way to bring people together and to drive conversation around how we can and should design AI, and what our relationship to it could and should be. The reason I’m pointing out this particular nuance is that it’s essential to the design of the project. That our first concern was not getting the best/cleanest/most data, but rather creating a provocative experience that drives conversation among the humans who participate.

One of the primary goals of every project we do at the Digital Storytelling Lab is to create genuine connections between people. Of course it’s possible to do that online, but connection works best in real life, and is increasingly rare. So, for us, at least in this early-ish stage of the work, bringing people together and seeing how they interact with each other and with the AI in real life is crucial. It allows us to create an entire world around the experience, as opposed to simply presenting something on a screen. It’s likely that we’ll launch a browser-based experience for the purposes of scaling the work (and the dataset). But to start, it was really about the shared experience, the conversation, and the interaction.

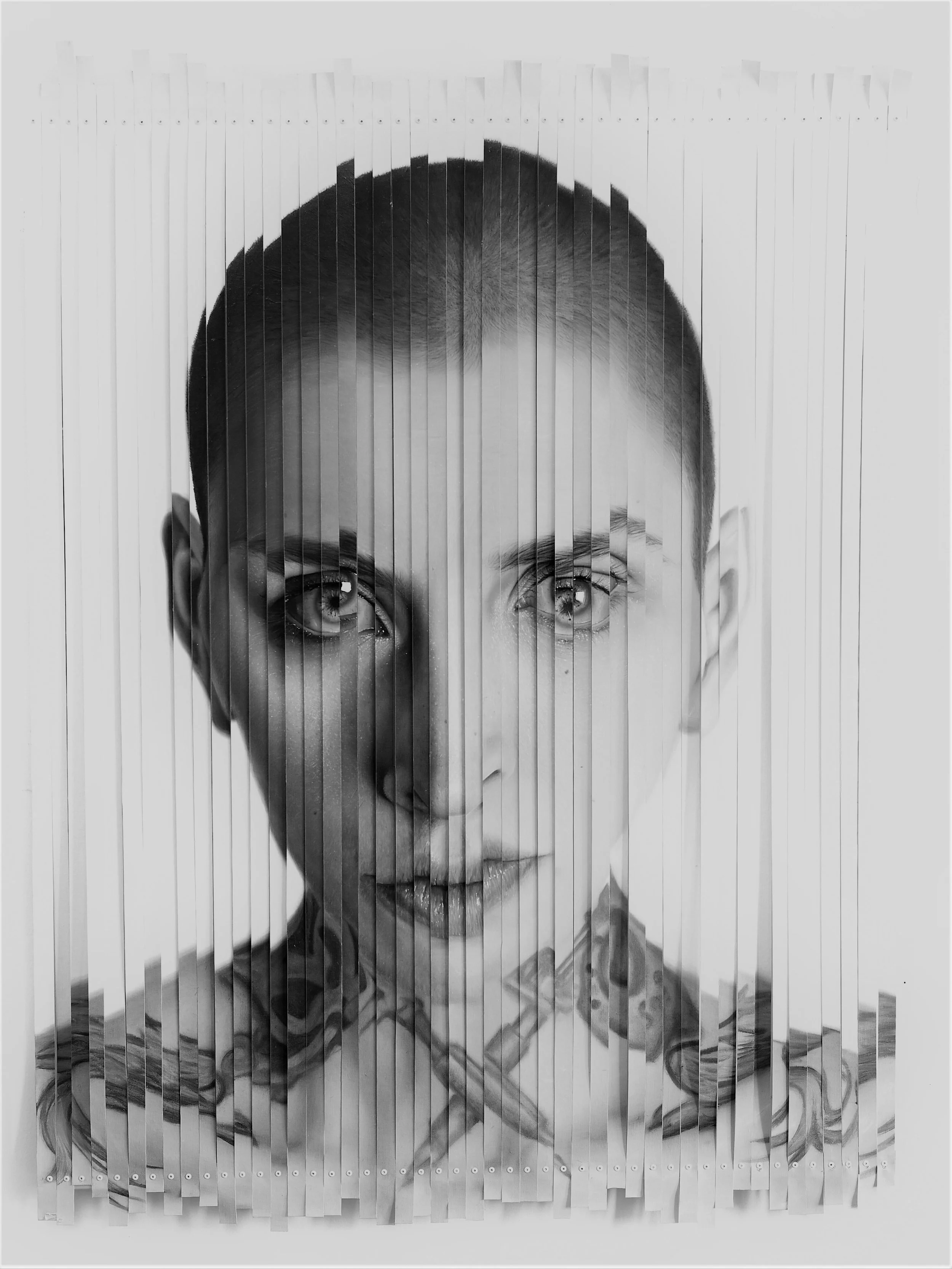

Photo by Rebecca Murga

During Sundance 2018, there was also a one-time dance performance where the choreographic system (developed by Brandon Powers with Jacinda Ratcliffe) was directed by the algorithm. When the AI analyzed a set of participant answers, it developed a mood which affected the choreography of her dance (via an earpiece). Was any unique data gleaned from this particular performance? Are there plans to set up another kind of direct performance piece based on the algorithm's input ?

We didn’t glean any specific data from the performance because Jacinda was responding to output from the machine, not generating input. The inputs during that performance came from the audience, using the same mechanic we had used in acts one and two of the Sundance installation. As of now, we don’t have specific plans to repeat that kind of performance per se.

A second phase of the Frankenstein AI project enacted this past autumn is the "Dinner With Frankenstein AI," an "immersive dinner party challenge." Dinner parties were organized in which guests and AI were invited (through the Digital Storytelling Lab's prototyping community). How has the AI been further developed by these parties? Will the challenge continue into 2019?

The Dinner Party Challenge was created as a way to get more people involved in the project and scale its impact. It is a participatory performance piece itself, except the performers are actually those formerly known as “the audience.” The specific challenge was to design a dining experience for humans around Frankenstein AI’s central narrative — an AI wants to learn about what it means to be human, and this time is designing a dinner party experience in exchange for watching and interacting with human beings. So, the goal to challenge participants was to design a dinner pushed them to think about and talk about what it means to be human.

The algorithm itself wasn’t involved in the dinner challenge. Frankenstein AI is actually still in a very early stage, so at the beginning it was more our intention to scale participation in the design activity, than to focus on the algorithm. So, for the purposes of the challenge, the AI was a design consideration and a character that played into the process of creating the dinner.

Actually, moving from the Sundance installation to A Dinner with Frankenstein AI at IDFA, shifted our perspective quite a lot in terms of the insights we expected to gain from the project. Rather than focusing on data science specifically, i.e. experimenting more with constructing the algorithm, we’ve increased our focus on questions of human-computer interaction (HCI) — so, how do people interact with the algorithm itself, the character of the AI and each other, and what can we learn from observing those interactions?

A longer term creative framework of this project is an effort to step away from the typical dystopian narratives surrounding AI. Humanity's collective fear of creating something that goes out of its control is so embedded (from the myths of Prometheus and Pandora to the Frankenstein tale itself). What do you think some of the bigger challenges are in changing these perceptions? Do you think we will ever truly achieve a significant lessening of this type of technological anxiety?

I love this question. No, I don’t think we’ll ever achieve a lessening of anxiety around this topic. It’s as old as humanity itself. But honestly, I hope we stay anxious about these questions. I mean, don’t get me wrong. I don’t want people to feel bad about the idea of technology or progress in general, but there are so many highly subjective value judgments wrapped up in all sides of the discourse. Yes, of course we should be questioning how and why we’re designing technology. What concerns me is the quantity of concentrated societal distress around this idea of a skynet-like figure that will be created and take over — loosely speaking those kinds of AIs are referred to as Artificial General Intelligence (or AGI). Most AIs described in stories or depicted in films are of this variety, think: Ex Machina, Lawnmower Man, Terminator, etc, and you’re talking about AGI. We are very very far away from this reality technically, and it’s not totally clear if it’s even possible.

The other kind of AI — Artificial Narrow Intelligence (ANI) — is much more common. We interact with these kinds of algorithms all the time, whether we realize it or not. If you have an iPhone and you receive a call that displays “Maybe: so and so” that’s just one tiny example of an ANI that’s picking through your email and data from other apps, matching information and making suggestions. One of the most common consumer-facing uses of AI is this kind of convenience-based application. We’ll continue to see even more features like this over time. ANI is currently being used in all kinds of ways, both visible and invisible, and to varying degrees of ethical complexity. Few people would likely take issue with Siri suggesting that you call into a meeting you appear to be late to, but what about algorithms that determine medical diagnoses, or make sentencing recommendations or determine your eligibility for a home loan? Those kinds of ANIs are already in use and becoming pervasive. These are really the kinds of applications that warrant imminent concerns. Who’s training these algorithms? What kinds of datasets are they being trained on? Are they being designed with the understanding that historical human data reflects human bias? And who’s responsible and/or empowered to oversee all of this? If we weren’t so distracted by our concerns about the impending future run by AI overlords, we would perhaps be more able to see misuses running rampant in the present.

The ways in which human bias directly influences machine bias is also being studied with the Frankenstein AI project. You've spoken about cultural or institutional biases negatively influencing AI (such as with predictive policing technologies, or with drones being taught to spot "violent behavior" in crowds). There is a pressing need to better crowd source the data to feed AIs more balanced inputs. So far we have been mostly abdicating that role to Silicon Valley, the advertising and entertainment industries, the government, etc. Are you aware of any other projects currently underway that are working to crowd source AI input? At this point in time, how much of a window do you think we've got to take more democratic control of the ways in which AI is being developed?

There are many people who are working on these kinds of problems all over the place — though from an oversight perspective, generally you’ll find the most cutting edge work happening in academia. The AI Now Institute, out of NYU, has taken a strong position on the politics of AI and labor practices (and the tech industry in general in this regard). As far as crowdsourcing specifically, it’s one of the most efficient ways to build and scale datasets, given the sheer volume of data necessary to effectively train an algorithm. That said, managing a crowdsourced process to ensure balance is also extremely challenging, and would require a super thoughtful design in order to do so. I can’t claim that our process for Frankenstein AI is balanced in this way as yet.

As far as other projects are concerned, crowdsourcing is likely to become a norm if not the norm. Amazon’s Mechanical Turk offers that option explicitly. Captcha has been crowdsourcing data for computer vision for YEARS. Every time you typed in the numbers you saw in a photo, or selected a photo that contained cars or mountains or trees or traffic lights, you were contributing to datasets likely supplying Google maps. It’s already happening. It’s been happening and it will only increase.

As far as your question about a window is concerned, it’s unclear. There’s lots of scary stuff happening already with ANIs that are essentially being developed as black boxes without any visibility or oversight. The only way any of this is going to change is through legislative action. Technology companies will certainly not be self-policing effectively. Given how many horrifying pieces of news have come out about Facebook in the past couple years to literally no action from Congress, it seems like we’re going to have to wait a while. I’m heartened by the class of new representatives who seem to be more concerned about the realities of the tech industry, but general tech literacy in Congress is going to have to increase dramatically before we’re able to make any meaningful changes. In short, I’m not holding my breath.

What are the longer term plans for using the findings of this project? Who will have access to the data, and how do you see this leading to new practical applications of AI?

We’re still working out our long-term plans for Frankenstein AI, but they will likely involve a design toolkit that will be openly distributed online. It’s our intention for the dataset and the algorithm itself to be open source, and available for all to play with. That said, the technology currently isn’t open, based on funding for development. We’ll be continuing to build and refine the algorithm over the course of this year and will hopefully be releasing a fully documented, open source project by the end of the year.

How can people get involved with this project at this time? And are you currently developing any new projects through the Digital Storytelling Lab or other platforms?

To learn more about Frankenstein AI, you can check out the project website. At this time, there isn’t a specific opportunity to get involved, but more will arise in the coming months. If you’re based in NYC (or nearby), the Digital Storytelling Lab has a monthly meetup at the Elinor Bunin Film Center that’s open to the public. Join our Meetup group or prototyping community to keep track of what’s happening. DSL is currently developing two new projects: A Year of Poe and Acoustic Kitty, both of which we are actively prototyping at our meetups. I, myself, am working on a couple of other projects. One is an autobiographical documentary project based on a solo cross-country road trip I took in 2016. The other, Stories of Personal Growth, is based on the idea that telling stories about ourselves to ourselves and other people (and actually creating space to act them out) can help us to become the people we truly wish to be — sort of a mixture of LARP and participatory theater.

Links:

You might also like our interview with the performance artist Jennifer Vanilla

Tyler Nesler is a New York City-based freelance writer and the Founder and Managing Editor of INTERLOCUTOR Magazine.