EMILY PETTIGREW

Emily Pettigrew paints subtle and sparse landscapes and visual narratives. In this interview, she discusses the scenery of Maine and its influence on her work, the narrative sources for some of her paintings, and the details of her recent “Earthworks” triptych.

Interview by Megan Farrell

The majority of your works are landscapes and outdoor scenes. Are the landscapes you create based on actual places you’ve traveled to, or are they from your imagination and memories from when you were younger?

They are a combination of memory and invention. I sometimes work from life or from my photographs to begin a piece, but I don't like to finish onsite or from an already existing image. This is because the paintings are a projection of my interior life and function as my correction to and revision of the universe. They are about longing and the creation of an enclave of conditions in the external world with which I am completely in harmony.

You’ve stated that you refined your minimalist style from your upbringing in Maine, which is an interesting choice for landscape pieces in general. What about your upbringing in such an outdoorsy place created this desire to paint such stark experiences?

I think the Spartanism of the Maine landscape and architecture leaves a mark on all its artists. People like Will Barnet, Alex Katz, Andrew Wyeth, and Fairfield Porter all have a cleanliness and clarity to their work that is very characteristic of New England. I see myself as part of that tradition of Maine painters.

The acrylic paintings that feature lone figures — or pairs of figures — among the landscapes, often give off a solitary or melancholy feeling. What draws you this feeling of isolation?

People often say they experience my paintings as lonely. It’s interesting to me because I almost don’t notice that effect. I think growing up in a remote place and without siblings of a similar age to me profoundly shaped my personality. I feel most alive and most like myself when I am alone. I also find my experience of the world when I am alone to be more meaningful and profound and my paintings reflect this predilection to isolation.

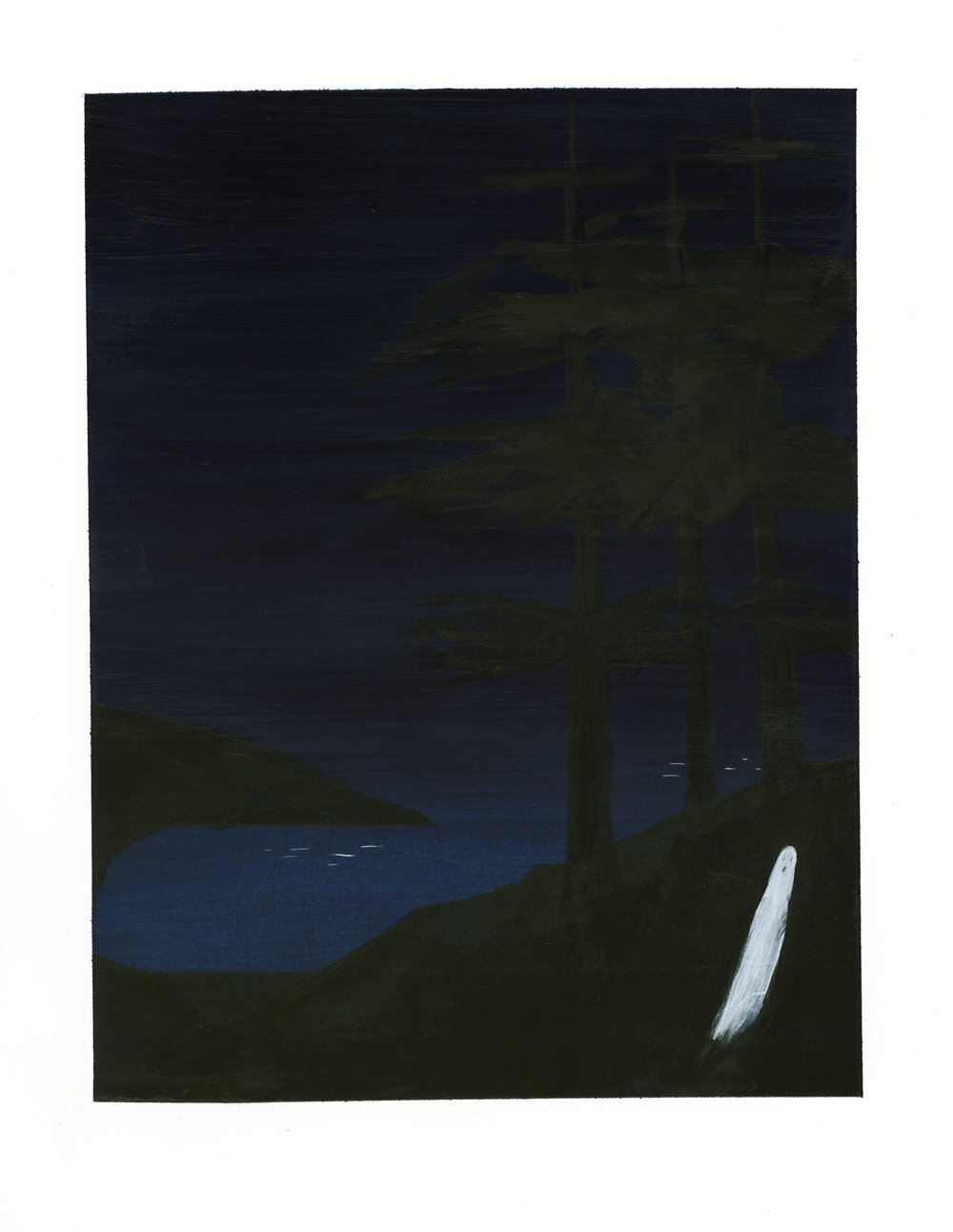

"Pilgrimage to Sacred Stones" - acrylic and graphite on wood, 2018

“Country of the Pointed Firs,” acrylic and graphite on wood, 2017 - piece based on the Sarah Orne Jewett book of the same title

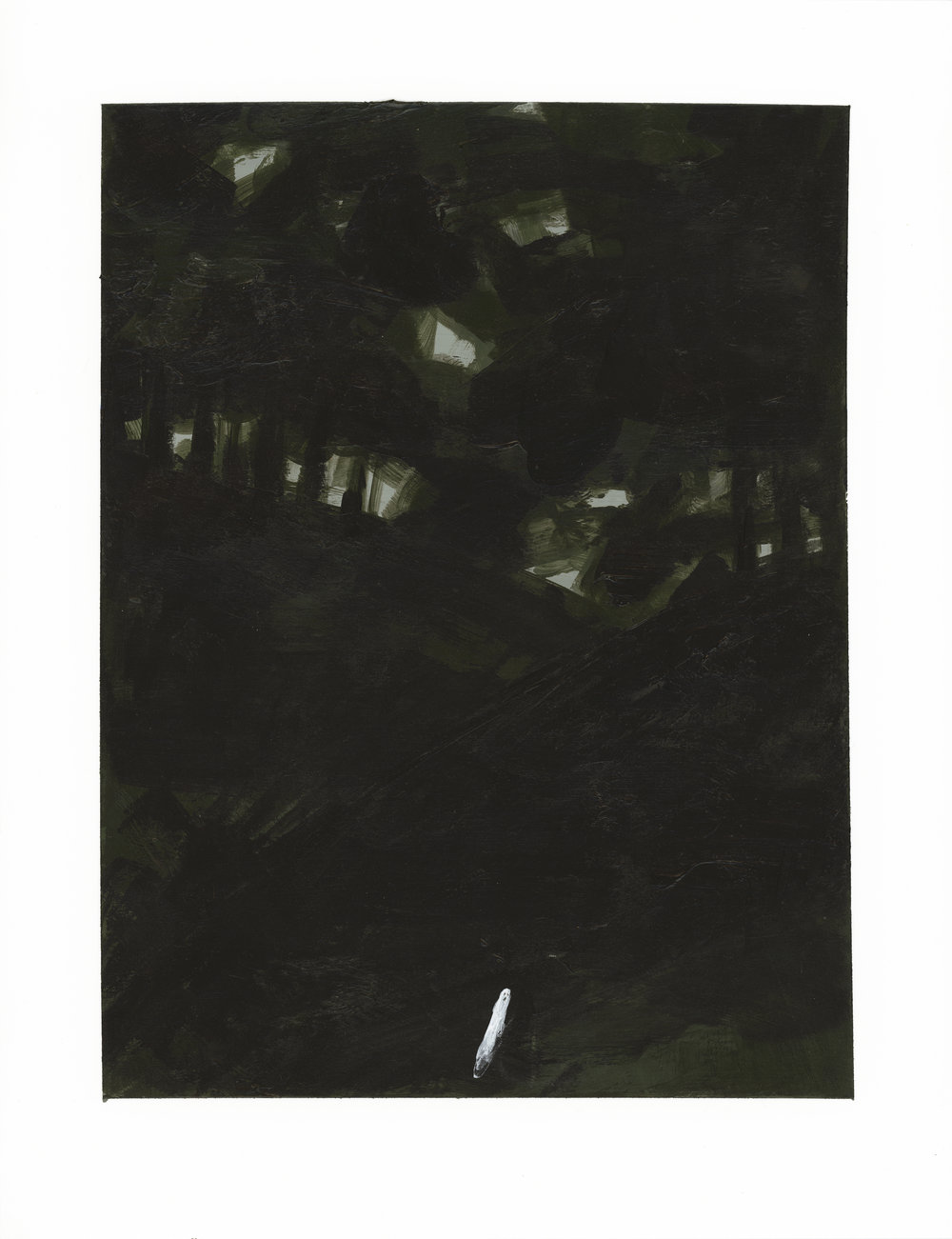

"Cill Rialaig" - acrylic on paper, 2019

You often name your paintings after specific moments in films or stories, such as “Sky West and Crooked,” based on the John Mills film, and “Opposite the House of Caryatids” from Doctor Zhivago. Are these interpretations of the films, or a representation of the overall tone that the paintings evoke?

Many of my paintings are encapsulations of narratives, either sourced from books I’ve read, personal mythology, autobiographical stories, or the stories of the old folk ballads that were once strongly embedded in our collective consciousness. I think the “Sky West and Crooked” painting was the only one that was more a representation of a movie than a book. I feel a little blasphemous saying this, but I thought John Mill’s movie was better than the original D.H. Lawrence book, which was called The Virgin and the Gypsy. “Opposite the House of Caryatids” is the title of the chapter in Doctor Zhivago in which the two main characters are reunited. I would say, my older work is more an interpretation of a story that I sourced from elsewhere. My current work has evolved into my own constructed narrative that I often associate with an existing title from the literary canon.

“Opposite the House of Caryatids” - piece based on Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago

“Skywest and Crooked” - piece based on the 1966 John Mills film of the same title

There’s a recurring theme of ascending ghosts over islands and houses in your acrylic narratives (“Ghost Scared From a Bush,” “Maid on the Shore,” “All For a Young Fellow Who Lately Deserted Me,” “A Maid Making Great Lamentation,” “A Blacksmith Courted Me”). What is it that draws you to such a subject? Are they all part of the same narrative story, and if so, would you say that the narrative has the optimistic view of the ghost finally being free, or is it a tragedy because the subject ended up as a ghost?

I found people really responded to the ghost paintings! To me, the ghosts are both tragic and funny. They are powerful because they are an archetypal symbol of pathos and mortality but at the same time can be interpreted as something more petty and ephemeral like the “ghosting” phenomenon in modern dating. Most of the titles of those pieces come from folk ballads about a young woman who is abandoned by her lover. I’d say, the theme of the whole series is female abandonment. I like that they indicate familiar folkloric stories, but no, they don’t depict any single one.

When you’re not painting, you work in a rare books store in New York. Is there an element of inspiration that you get from being surrounded by books?

Absolutely! Literature and history strongly inform my paintings. I am a bibliophile and I read and collect old and rare books. I often draw inspiration from what I read, and I am constantly learning from the breadth of historical book illustration I work with on a daily basis. The type of material I usually get to handle ranges in date from the 1400s up until the mid-1900s. I am currently reading Laxdæla Saga, which is one of the Icelandic epics, written sometime in the 1200s. It’s fascinating, and I’m sure it will end up informing some future paintings.

Some of the smaller works on your website are created on MetroCards for the Single Fare Show, which is an interesting presentation. Did you find working within the limitations of such a format restricting and rigorous, or more freeing experience?

As a painter, I usually get to follow my own dictates and am totally in control of my work. When working on a project like the MetroCard paintings, where someone else has specified a limitation, I am forced to adapt and end up surprising myself with the result. Painting is a very solitary activity and so it is sometimes beneficial to interact with someone else’s requirements or themes for a piece.

"Earthworks" triptych - "Chalk Circle", "Standing Stone", and "Ceremonial Pool," 2019

There was a series of “Earthworks” triptychs recently displayed on your Instagram account, which is quite a divergence from the outdoor paintings that you feature on your site. What are these pieces made of, and how did you reconcile a new medium like three-dimensional structures with your signature style?

The bases are painted wood, like most of my paintings, and then the sculptural element is applied architectural model foliage and a rock I picked up from a painting residency I did in a restored, pre-famine village in Ireland. I see them as somewhere between paintings and sculptures because they are still quite flat, rectilinear, and could be hung on the wall. I think this idea was definitely influenced by Ryan Steadman’s book stacks, which are both paintings and sculptures at the same time. The pieces are intended to be reminiscent of ancient and archaeological sites in the British landscape that have taken on mystical meaning, like standing stones, chalk figures, and ring ditches. I have always been interested in the British Isles because of the abundant and tangible presence of human history in the landscape. This interest has been reflecting itself more in my work since returning from my artist residency in Ireland.

View more of Emily’s work on her site and on Instagram.

You might also like our interviews with these artists:

Megan Farrell is a twenty-two year old writer and filmmaker who lives in New Jersey. She has recently graduated from the University of Alabama with a dual degree in Telecommunication/Film and Economics. In her spare time, Megan enjoys amateur photography and playing tennis.