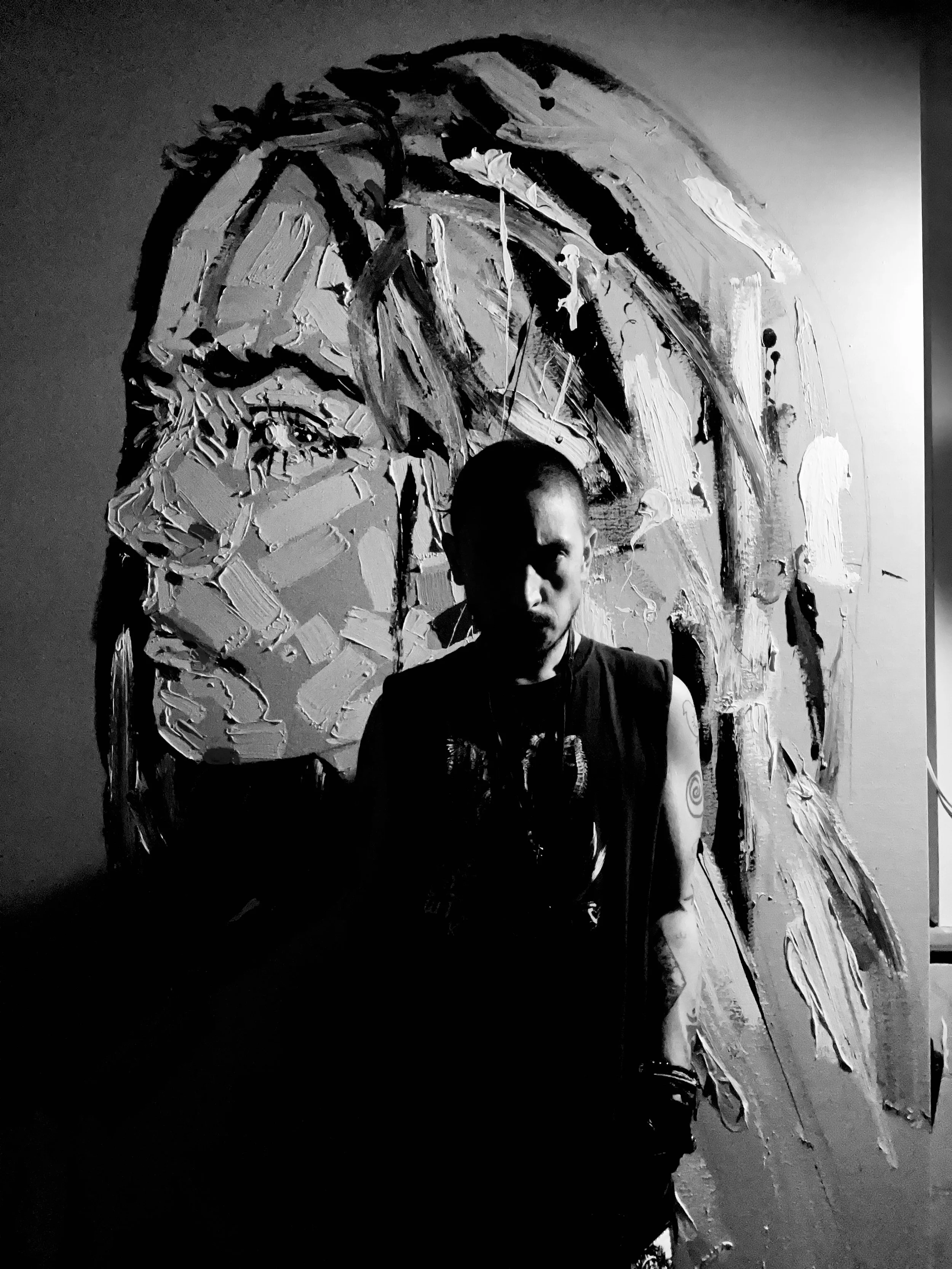

NICK BAUTISTA

“What We’ve Done To Each Other” - 2020 - acrylic and charcoal on canvas, 68-1/2 x 58-1/2 inches

In this interview, New York-based artist Nick Bautista talks about the risks of overthinking and over explaining art, his process of developing his works, what commercial success can mean to an artist, and the ways that the art world has radically changed since the start of the pandemic.

Interview by Liam Kelsey

How do you believe your formal training has influenced the development of your work?

Formal training is so important. I had the wonderful opportunity to work with some amazing artists when I was a student. They looked after me, one artist in particular, and he really challenged what I was doing or how I was seeing something. It provided me the foundation for my work so I know what I’m doing when I break certain rules or take certain liberties, in a way. I like to make sure each mark I make has a purpose behind it.

You’ve mentioned that your recent series "How The Fuck Did I Get Here?" was done without overthinking. What are particular qualities to this series that have freed you from overthinking the process?

The looseness of the forms. The mistakes – I enjoyed those qualities with this series. Overthinking can be a slippery slope. It’s good to have an idea, a solid composition, a direction – but obsessing about every detail can take away the magic of it. The little drips, or perhaps a too aggressive brush stroke gives the painting a life. It feels like it’s breathing. It looks like it has seen some shit. I had to let go of my own ego, stop thinking so much and just let the painting happen.

“An Inevitable Ending” - 2020 - acrylic and charcoal on canvas, 68-1/2 x 58-1/2 inches

You’ve also said that paintings should have visceral meaning. What do you think the challenges are of impacting others with the visceral nature of a work that is rooted in personal experience? How can those personal legacies similarly impact other viewers?

The challenge is that everyone has their own history. My personal experiences don’t have to be everyone else’s experiences. I can’t make a painting, worrying about whether someone understands it or not. I can’t make a painting for someone else’s sake – it has to be for me first. But perhaps someone does connect with it. Maybe they get it, or it reminds them of something in their life. If that has an impact on someone, then great, I can feel good about that – that’s an intimate connection.

Many of your works depict individuals in a very stylized and expressive manner. Why do you feel you're attracted to depicting abstracted figures as opposed to other types of imagery?

I have always been fascinated by the human figure. It’s a beautiful thing we all have – these bodies. It can take on endless forms, express a multitude of emotions with just a simple movement – that’s everything. When I was a kid and in art school, I was entranced with what de Kooning had done with the figure, what Bacon had done, even Lester Johnson. There was so much emotion, aggression, and pain in those paintings. That was my outlet growing up – painting and drawing. I had a difficult time expressing how I was feeling or what I was feeling. But I could get it out, visually, on paper and canvas. Using the human figure as a basis was how I could articulate those feelings.

“The Past Tastes Like Scrambled Eggs” - 2020 - acrylic and charcoal on canvas, 40x40 inches

“A Paradox Walks Into a Bar...” - 2020 - acrylic and charcoal on canvas, 50x92 inches (Diptych)

On the other hand, your recent series "Mountain Mantras" differ from much of your output in that they seem more like pure abstract expressionism, with no obvious figures. How is your approach to these pieces different from the more directly personal inspirations of your "How The Fuck Did I Get Here?" series?

Yes, this is my first series of non-objective work; almost landscapes if you will. Although there is a lot of ambiguity with these paintings, they are still very personal – perhaps more so than anything I had done previously. They reflect on this four year journey I took, culminating in a ten day event in the mountains. It took me six years to process that journey and put paint to canvas. There was no way I could express what I wanted to with the human form – not in this instance. The events that make up this series involved physical pain, starvation, sleep deprivation, hallucinations, life threatening injuries…there were experiences that transcended what the the human figure could do for me - it was madness. I decided I needed to address this experience with pure emotion and just paint. I forced myself to relive those experiences in a sort of meditative state and just let go in the studio. I did these as more of a cathartic process than anything, but I have received a lot of wonderful messages from people. These paintings are quite large and I only have four of them completed, but there are about five more I need to paint.

The Final Climb - 2020 - acrylic and charcoal on canvas, 70 x 80 inches

“The Spirit Breaker (5 hour loop)” - 2020 - acrylic and charcoal on canvas, 70 x 80 inches

Where does a work usually begin for you? When you start, do you always have an idea of where you’re going, or is it more a dynamic process of discovery?

I draw in a notebook on a daily basis, so that’s where a painting begins. I’ll draw from life or rework from photo references I’ve taken. There is always an idea of where I am going with a series. I do my best to research my ideas, make countless sketches and studies and write about what I’ve discovered. From there, I just let the painting happen. That’s where the fun is – seeing where an idea goes from where I started. It’s like road map – you’re following a route on a map towards a specific destination, but you make a wrong turn. And then another wrong turn. At some point you say “fuck it,” throw away the map and see what happens.

Do you think that using words to explain the intent behind a work automatically minimizes its visual impact? Are paintings and drawings essentially working in their own language that is by necessity purely visual and not well translated into words?

I do believe it minimizes the visual impact. I got into some trouble with this in grad school, when all of my professors required “the artist statement.” I was so against writing one. If I needed a statement to explain my paintings and intent, then what was the point of painting at all? For sure, it is its own language. I was definitely the outcast in my MFA program, because the artist statement is just a given in the art world – but I never believed in it. I have my mentor to blame for that. He was a professor of mine all through art school, and my dear friend years after - a well known and celebrated artist in his time. He passed away in April. I remember years ago, he and I talking in my studio when I was student, and he said, “When looking at a painting, if you can’t pull from your own intelligence and your own personal history and experiences, and form an opinion or conclusion about what you’re looking at, then you don’t fucking deserve to know what it’s about.” I always loved that, and it always stuck with me.

What has commercial success been like for you? Is it validating, or do you see serious risks with seeking validation from external sources?

Commercial success is not my, nor should it be the goal, of any artist. That’s just how I feel. Sure, I can sell a painting and it results in money, but money doesn’t last. I paint because I love painting. I love being able to make images for myself and being able to have an outlet for what I am feeling. If someone connects with that, then I am happy to have painted it. Any artist who makes what they are making for the purpose of monetary gain or approval from the masses, especially in the social media age, is just bullshit. I’m sure I will get shit for that comment, but, that’s what I believe. The art you’re making needs to be for you first. I feel that if art is made to please everyone else or shocking for the sake of being shocking or made to get social media hits, it becomes this watered down and dishonest dribble.

How do you think the commercial art world will change as a result of the pandemic and the ensuing economic crisis? Do you foresee more serious, structural changes to the way business is done?

I just got signed by a gallery in Chelsea (Agora Gallery) right before the pandemic; my first NYC gallery. Typically it’s straight forward business when a gallery represents you. But with everyone having to be isolated, businesses closing, folks losing their jobs, etc…everything has to change. I have seen galleries adopt virtual platforms, my own gallery included, to allow people to experience an exhibition in their own homes. It’s great, so the work can be seen, but it’s just not the same. You can’t experience the size of a painting, the texture, the smell of paint through a computer or phone screen. I have no idea what will come in the next few months or years. But things will change. People’s health and safety definitely have to take precedence.

See more of Nick’s work on Instagram and his site

You might also like our interviews with these artists:

Liam Kelsey is a writer from Minneapolis, MN. His fiction, science fiction, and criticism have appeared or are forthcoming in Silver Needle Press and other independent publications. He would like you to read Break it Down by Lydia Davis and The Weird and the Erie by Mark Fisher. He would like you to listen to the band Pile.