GABRIEL BARRETO BENTIN'S Peruvian portraits

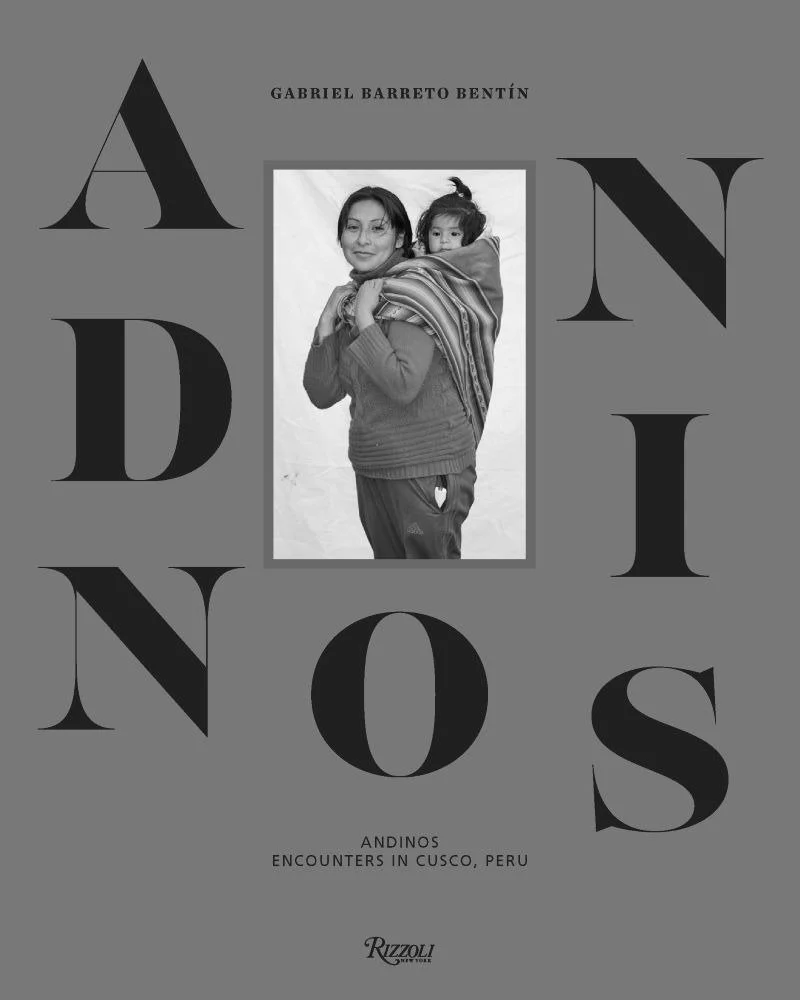

Peruvian photographer Gabriel Barreto Bentín is pleased to announce the release of his first photo book, titled Andinos: Encounters in Cusco, Peru, published by Rizzoli and with a forward by Ruven Afanador. Barreto collaborated with Peruvian anthropologist Francesco D’Angelo to create a socio-anthropological, photographic study that offers a unique perspective on the Andino people, exploring narratives of spatial modernity and social hierarchies, and challenging the commonly portrayed cliché romantic versions of indigenous people pictured against breathtaking landscapes devoid of social context.

Much like the Humans of New York for the people and indigenous culture of Peru, Barreto traveled to Cusco and the Sacred Valley to photograph locals against white backgrounds, focusing on how they dress for different types of work and occasions. The images portray the diversity of the Andean people through their faces and attire, irrespective of the landscape. The portraits are accompanied by observations by neighbors from nearby communities – interviews that explicitly guide the reader through the articulation of modernity in the Andean society of Cusco.

Purchase a copy of the book online at the Rizzoli website.

Interview by Interlocutor Magazine

What were some initial inspirations that sparked this project - any particular photography books or portraiture series that gave you a creative framework and set the idea into motion?

Right after I finished high school, in 2016, my uncle and I went on a road trip from Lima to Cusco for a month. Inspired by the kindness of the people and their authenticity, I began to work on what would become Andinos: Encounters in Cusco, Peru. As soon as I came back from this trip I started looking for different ways that I could approach the project, Richard Avedon’s In The American West instantly jumped out. I was especially interested in the way he decontextualized his subjects from their surroundings to empathize the importance of their individuality by using a simple white cloth.

Evelyn Choquepata, Oropesa, 2019

How did the Peruvian anthropologist Francesco D’Angelo become involved? Have you worked with him before, or is this your first time collaborating?

Francesco and I have known each other for a very long time, our families have always been close, but we had never worked together. After my initial experience in the Andes in 2016 I had thousands of questions, crazy ideas in mind, and a lot of energy, so my first thought was to speak with Francesco. At the time, Francesco was living in a community in Maras, Cusco as the anthropologist for a restaurant that was opening nearby. He helped me settle on the first community I visited, Kaccllaracay, and we spoke about many of the ideas from the project. Francesco became officially involved in 2019, after I had spent many months living with and photographing the Andes, when I started to question how we could use these portraits to create a dialogue between Andinos.

Gilbert Feria de Tiobamba, Maras, 2018

Photographing your subjects against simple white backgrounds is a unique approach - why did this method appeal to you over the more common and romanticized landscape settings that are the typical backgrounds for images of Andean people?

Many of us who are not familiar with the realities surrounding the Andean society of Cusco view them through a problematic dichotomy. On the one hand, “The Perfect Postcard” shows the Andes as a magical, lost-in-time place, and the Andinos as pure and almost magical people who are a static version of old folkloric tales. On the other hand, in “The Image of the Poor,” we can observe an insensitive and antiquated postcolonial narrative elaborated by the people of the capital to project a sense of superiority over those who did not inhabit the economic center of the country.

The white fabric allowed me to place the focus on the person being photographed rather than on the breathtaking landscapes often pictured by photographers who have hitherto attempted to replicate the Andean environment. In doing so, I hoped to portray the diversity of the Andean people through their faces and dress, irrespective of the landscape. The intent was not to deny the importance of the environment, but to draw closer to the people rather than to the romanticized versions of Andinos often depicted in photography, in which the subjects tend to fade and the backdrop shines.

Jordi and Messi Choquecancha, Lares, 2019

Observations accompany the portraits by neighbors from nearby communities. What were some surprising insights you gained from these interviews, and why did you feel these observations were important to include with the photographs?

Using the portraits I had taken during my travels, Francesco devised the methodology to interview neighbors from nearby communities about who they thought the people photographed were, where they thought they lived, and what they thought they did for work, among other questions. By doing so, we meant to break through the stereotypes often associated with Andinos and see how the people themselves see each other based on the perspectives of local people about other Andinos.

Through these captions, we are able to see how Cusqueños relate the traditional to the rural and the modern to the urban; progress and modernity are understood as the distance a person stands from the “dirt.” One can see this interplay in the interviews with local Andinos, as they note the dichotomy between themes such as: open shoes versus closed shoes, high altitude versus low altitude, uneducated versus educated, and agricultural versus nonagricultural. At the same time, symbols of modernity stand out to people, such as a laptop representing a good education, a paid job, and a home in the city. These interviews show the complexity of defining modernity in simple terms, as well as the social logic at play in local Andean perspectives.

The book includes a forward by celebrated Colombian photographer Ruven Afanado. What do you most admire about his work, and what is it about his voice and perspective that you thought would make an ideal introduction to this photo series?

I have been a huge admirer of Ruven’s work for many years now; when I was starting as a photographer in Lima, Peru, he was invited by a magazine to shoot their cover, and I had the amazing opportunity of being on set to see him work. His affinity for lighting a scene and his ability to pose his subjects like a naturally formed sculpture was something incredible to witness. I then came upon his fine artwork, Mil Besos & Angel Gitano are two of my favorite photobooks in my collection. His interest in photographing Hispanic culture and exploring where we come from was always an important inspiration for me. Hijas del Agua, Ruven’s latest publication where he photographs indigenous communities in his home country of Colombia, shows us the importance of his voice and perspective when thinking about Latin American art.

Ruven introduces my photo book through his own personal experience with the Andes, his connection with Peruvian photographer Martin Chambi, and how Irving Penn opened this world up for him. The generosity of his words and how he connects my work to this incredible line of photographers, including himself, left me completely speechless.

Luz Marina Cuyo Grande, Písac, 2019

You have also done commercial fashion, beauty, and design photography. How do you think this work may have informed your approach to more fine arts-oriented documentary/portrait photography, especially regarding this project?

When I started out as a photographer, I was marveled by many of the technical aspects of the craft. Lighting a scene with six different strobes all meticulously hitting different parts of the frame to create a perfect composition was one of my favorite parts of being a photographer. Throughout the years doing commercial photography, I was able to explore these lighting techniques in ways I never thought possible. For this project, I wanted to get rid of the exquisite lighting, the apparently perfect compositions I often came back to, the exaggerated poses I directed, and even the idea of telling a story, so that I could concentrate on my subjects. I was able to strip away everything I had learned to amplify the importance of the person in front of my lens and what was happening between us.

Purchase a copy of the book online at the Rizzoli website.

Gabriel Barreto Bentín is a New York City–based Peruvian fashion and portrait photographer. He recently graduated from the School of Visual Arts, Class of 2020, with a Bachelor of Fine Arts in Photography & Video. Ruven Afanador is a Colombian-born photographer best known for his photographic portraits in Torero (2001) and Mil Besos (Rizzoli, 2009)