Ledia Xhoga discusses MISINTERPRETATION

Photo by Todd Estrin

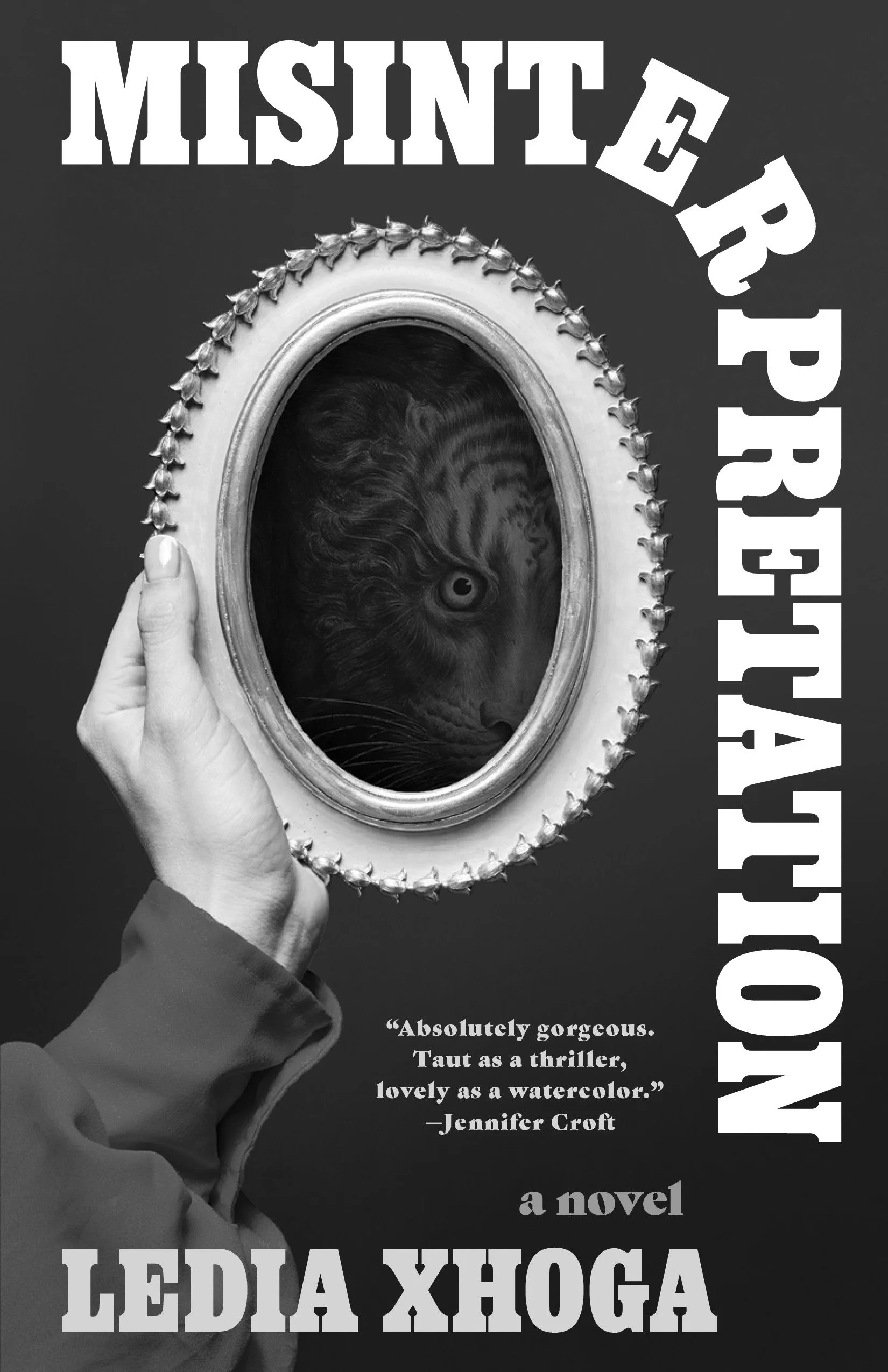

Ledia Xhoga (pronounced Joga) is a fiction writer and playwright. She was born and raised in Tirana, Albania, and currently lives in Brooklyn. Her debut novel, Misinterpretation, was published by Tin House Books. Her work has been published in Electric Literature, Lit Hub, Brooklyn Rail, Large Hearted Boy, Intrepid Times, Hobart, and other journals.

Interview by Nirica Srinivasan

The protagonist of Misinterpretation is a translator and an interpreter, and the book is (at least partly) deeply concerned with the effect of words — the protagonist at one point thinks, “Sometimes words affected me physically, causing as much nausea as motion sickness.” How do you think of the relationship between language and intimacy, especially as someone who, like the protagonist, lives between multiple languages? What initially drew you to write about that topic?

There are certain thoughts that only come to me in Albanian. Sometimes, it’s an old joke we used to say with my childhood friends — the sort of humor that is impossible to translate into English—or something relating to my family or close circles. In these situations, intimacy becomes enmeshed with the language. The alienation that all immigrants initially feel in another country is because of that undeniable connection. Assimilation is not only a survival mechanism but also an attempt to create a new kind of intimacy in a new land.

I didn’t set out to write about the topic; it came naturally after the story of the interpreter was on my radar, and I started contemplating her experiences. I also just remembered that during a real-life reading at the KGB Bar in Manhattan, where the scene you quoted takes place, the words of an author reading from her novel made me lightheaded for real, and I had to go outside to collect myself. It’s obviously possible to achieve an overwhelming degree of intimacy in a second or third language, too!

Misinterpretation features a range of characters, many immigrants, and there’s a real range in their experiences. I was also struck by the protagonist and her husband, Billy, who share a complicated relationship that felt vivid and real to me as a reader. How do you approach character creation in your writing? What was essential for you to avoid clichés or perhaps more black-and-white explorations of character, especially in a novel that features so many?

The other day I heard someone use the word titration. I found out it came from the French to denote the proportion of gold or silver in coins. It now means the concentration of a substance in a sample. When it comes to characters you have to think about titration, by which I mean the intensity or lack of a certain quality.

There are plenty of cliches that happen in the earlier drafts, I’m sure, but then you eliminate them during revisions. You add an unexpected sweet gesture, a dash of rudeness, a sudden bout of anger maybe, to create more complexity and make it interesting.

This is a literary novel with thriller elements (I found it so suspenseful!). What was it like to balance the suspense and the dread with the more literary or reflective elements? Did you have the plot planned out entirely at the beginning? Were there other books that blended the two genres you were looking toward for inspiration?

The balancing act came pretty naturally. After I wrote the scene where the interpreter follows Rakan to the shoe store, the novel took on a thriller vibe, and I went with it. I didn’t plan the plot from the beginning. There wasn’t a particular book I used as an example. However, I love literary thrillers and writers like Patricia Highsmith, Gillian Flynn, and Truman Capote. It’s true that I was reading a lot of mysteries and thrillers back then.

There’s a surreal, almost mystical quality to moments in Misinterpretation that I loved — a Bashō poem (“There is nothing you can see that is not a flower; there is nothing you can think that is not the moon”) becomes important to the protagonist; there are these surreal moments and conversations where the protagonist is either actually dreaming or is on shrooms; characters recur in the periphery of her life.

I was so intrigued to read in your essay in LitHub that Misinterpretation began as a dual narrative and that many of these very arresting details and characters actually originated in the narrative you removed from the book — you write, “that other story is present, although only visible from a special vantage point.” I would love to hear more about that process and, specifically, what it meant for you to lean into that kind of fantastical, strange, unknown world that we catch only in glimpses.

The narrative that didn’t make it to the novel had perhaps more in common with my past life in New York City than the interpreter’s life. In the years I was attempting to fictionalize, I had started to feel more comfortable in the US than ever before and realized that the crowds I gravitated towards were the artsy, unconventional kind, which threw parties similar to the ones I described in the novel. I felt like I fit in.

The other story’s function in the novel, at a subconscious level, was perhaps to illustrate that new, acquired type of intimacy. The fragments that remained in the novel worked well with the duality theme, I thought, becoming a potential way the interpreter could also engage with reality. The duality, of course, became more prevalent as the novel went along.

This is kind of related! There’s a playfulness in how you approach the idea of interpretation/reinterpretation/misinterpretation. One of the ways that’s explored is that Misinterpretation contains several film references, either directly named or obliquely referenced, and most of these movies seem to involve a reinterpretation of some sort.

Dirty Dancing remade as a Bollywood film; movies made in black-and-white and remade in color; and both a Polish and a Korean movie that present the viewer with dual/bifurcated narratives (the former reminded me of Kieślowski and the latter of Right Now, Wrong Then!). I wonder how you thought of duality in the book in general and how these references and the initial plan to write it as a dual narrative contributed to that.

It was exactly Right Now, Wrong Then I was referring to! And isn’t that a great title, by the way? If only it were that easy to get it right later. Yes, I’m a Hong Sang-Soo fan, and he inspired Anna’s boyfriend. Kim Min-hee won’t mind. But you’re the first person to notice it. The Polish movie referred to a film I once happened to see at a public library in Austin, TX, whose title or director I can’t remember.

The Indian Dirty Dancing also exists and is as similar to the American version as I described in the novel. Believe it or not, I was unaware of how much duality had turned up in the novel until I finished it. It was a subconscious process that perhaps originated from the structure I had tried to implement but that ultimately suited the main character who is trying to reconcile her Albanian life with her current reality and whose marriage could certainly use a do-over.

Specifically, what was the process of getting into the protagonist’s mind? We see her world through her eyes, which makes her a kind of unreliable narrator (insofar as everyone is the unreliable narrator of their own lives). Her relationship with her husband, Billy, is so complex, and her drive to help often leads her into pretty bad situations. Did you leave her unnamed for a reason? What was the most challenging part of writing her?

I first saw the interpreter as someone giving, but her generosity was targeted toward her community only, which I see people do. They help someone from the same country, even if that person might not need as much help as someone else, let's say. Her relationship with Helen illustrated that. She doesn't try to get to know Helen and automatically assumes she is rich because of appearances.

Then, I had to show this targeted obliviousness in her most private relationship, which is with Billy. She doesn't see him either, even though they live together. Of course, she assumes she does; that's part of it. I think I had the interpreter right from the beginning, but it was Billy who proved more of a challenge. How does a character remain likable while asserting their needs in front of someone intent on saving the world? And I wanted to name the interpreter in the beginning, but none of the names I was coming up with stuck and then I grew to like her anonymity as a contrast to how much we get to know about her.

Check out our other recent author interviews

Nirica Srinivasan is a writer and illustrator from India. She likes stories with ambiguous endings and unreliable narrators.

Did you like what you read here? Please support our aim of providing diverse, independent, and in-depth coverage of arts, culture, and activism.