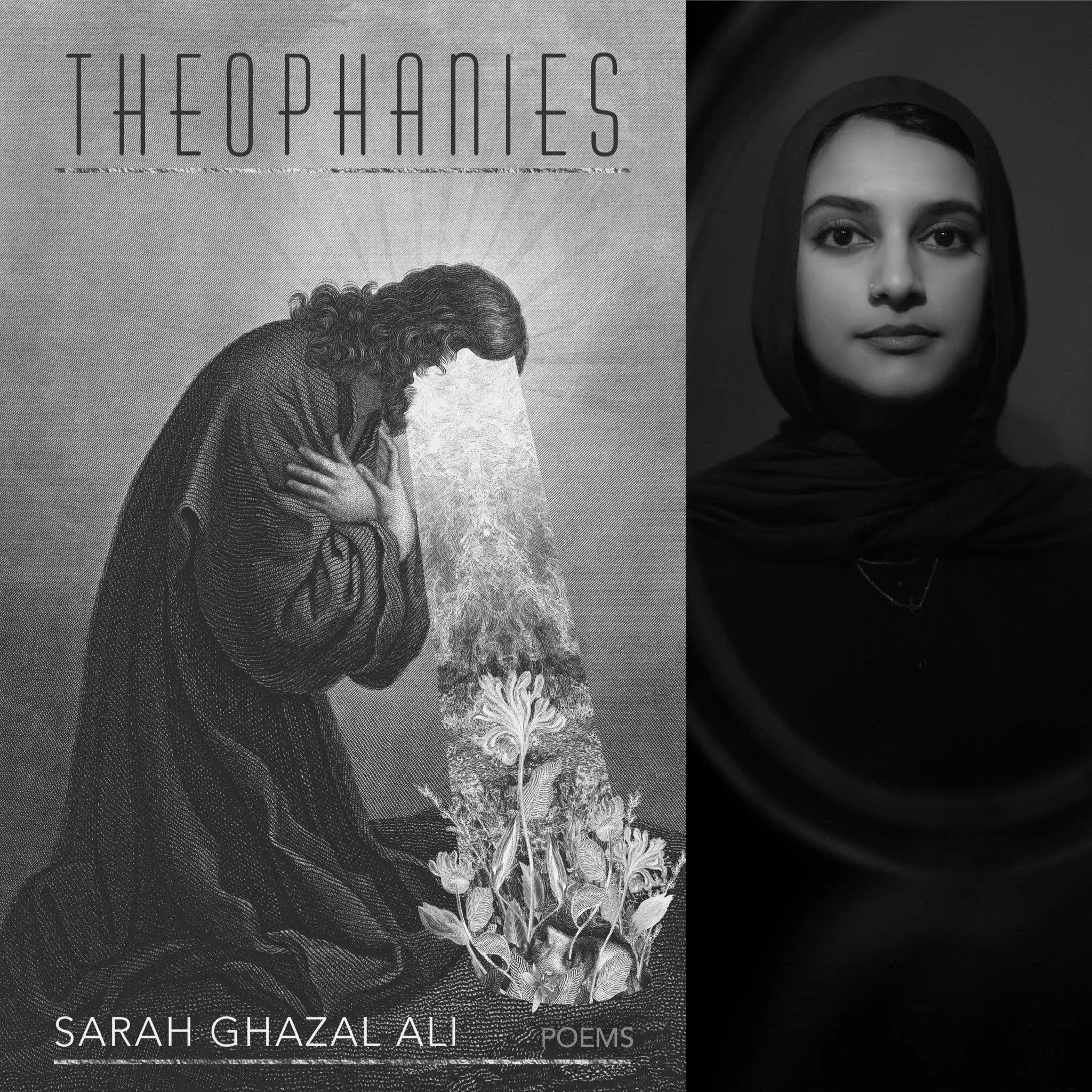

Sarah Ghazal Ali discusses THEOPHANIES

Photo by Beowulf Sheehan

Sarah Ghazal Ali is a poet, editor, and professor. Her debut poetry collection, Theophanies, published by Alice James Books, was named Editor’s Choice by the press in 2022. A Stadler and Kundiman fellow, she is an assistant professor of English at Macalester College.

Interview by Isabelle Sakelaris

Your poems are vivid—for example, in “Le viol, Rene Magritte, 1934,” you wrote: “I have seen a plum pucker in a man’s / tight grip, split sudden without protest / on the banks of the Sambre / vermillion sluicing his arm” (74). I love these lines because of the way you engage multiple senses—I can practically feel the plum juice in my own hands. What advice do you have for writers looking to expand on the sensorial aspects of language?

Slow down the way you consume language—try not to consume it at all, but to savor it, slowly, without skimming. Push yourself out of your own literary comfort zone as much as possible as an exercise. If you tend to reach for the image, try writing a poem that relies entirely on sound. Rewrite a poem you think is “done” and fill it with a sense you find uninteresting to work with. Always, always reach behind your first thought (or image, or metaphor…) for the more peculiar one, the one that you doubt or don’t understand.

A few other poets have written recently on similar themes that you take up in Theophanies, notably Leila Chatti (Deluge) and Mary Szybist (Incarnadine). Do you find comparisons based on content limiting? Which artists do you see your work in conversation or community with?

I don’t find these particular comparisons limiting in the slightest! They point to being read as part of a lineage. Mary Szybist’s work has been profoundly influential to me. Granted and Incarnadine are both lodestars for their strangeness and crystalline use of the image. Theophanies would not exist without Incarnadine as an example of what it means to engage with the mothers of faith, and to lean fully into obsession and repetition. My work is very much in conversation with both Deluge and Incarnadine; both Chatti and Szybist use form masterfully, and it is from their work that I first learned how much pleasure I find working in form myself. Some artists my work is in conversation with or owes much to include Agha Shahid Ali, Marie Howe, Brigit Pegeen Kelly, Etel Adnan, and Dan Hillier (whose art graces Theophanies’ cover).

Some of your poems consider dialectics, often in the context of faith, such as in “The Ideal,” which references immaculate conception. Similarly, in “My Faith Gets Grime Under Its Nails,” you write about the experience of “postur[ing] piety,” for example, becoming distracted by the fringe of a prayer rug instead of focusing on “God’s pristine names” (1). Do you find dialectics generative in poetry? How do you reconcile the limitations of the written word with conveying something “beyond the lattice of language,” as you call it?

Dialectics are the only way through the world that I trust, and ambivalence is my bread and butter. Poetry is where I turn to ask questions that lead to better questions. Answers that result in either/or rather than both/and in my opinion do not serve art. Language is all that I have to get closer to the truth of what I think. Poetry is language that tries to transcend language—I don't think this is an original thought of mine, but it is certainly the most capacious thought I hold to be true. Kaveh Akbar said “reject certainty, which exists only in the rhetoric of zealots and tyrants.” Staying permeable to the great overwhelm of the unknown is the wellspring of poetry for me.

In “Magdalene Diptych,” you write about witness and perception. On the verso, you write: “The one bright / gift of my life is that I was / witnessed” which opens the part of the poem on the recto, in two lines instead of three (70, 71). The poem ends with the personified painting telling the reader/viewer what happens when they become “tired of looking” and leave. Do you see poetry as an act of witness, reflection, or testimony? How are these modes of seeing (and perhaps writing) different?

I see poetry as a way to make the world I inhabit real to myself—to return to each specific tree I pass daily its each individual leaf, which I fail to see when I conjure instead the image I hold in my head of what a tree generally is. It’s a way to improve my ability to witness rather than itself a way to witness. Maybe those are the same thing, sometimes, but maybe, more often, they aren’t.

Many of your poems explore transformation, often in the context of the feminine— from comparing “spectacle” and “speculum” (in “Spectacle, 20-21), which share a root word, to depictions of matrilineage and musings on the transformation from girlhood to motherhood. Do you think transformation is a feminine process? Why or why not? What does femininity mean to you?

I think transformation can be a feminine process but it can’t only be feminine. To generalize about transformation would inhibit it. As a woman, I know it to be one feminine experience. But what is feminine to me is not uniquely feminine, so I struggle to say what femininity is, or was, or should be (the more I write out the word, the less real it looks—!).Today, it feels like being a vessel that never empties. Yesterday, it felt like performing congeniality. Maybe performance is what I’m circling. Femininity is, at least in my life, an ongoing negotiation of performance.

Check out our other recent author interviews

Isabelle Sakelaris is an art writer and aspiring poet who lives and works in New York City.

Did you like what you read here? Please support our aim of providing diverse, independent, and in-depth coverage of arts, culture, and activism.