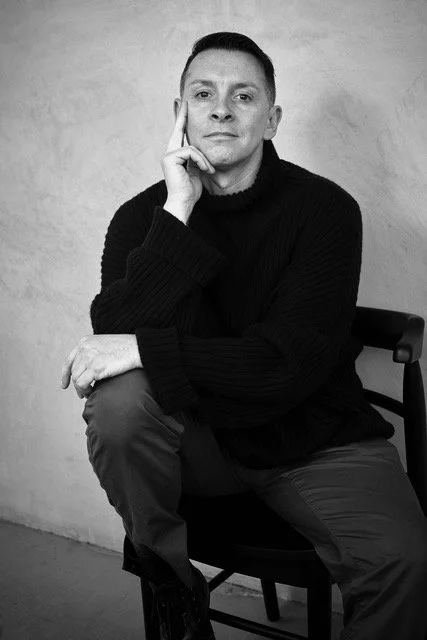

José Limón Dance Company Artistic Director DANTE PULEIO

In its 80th anniversary season at the Joyce Theater, opening this Tuesday, October 14, the José Limón Dance Company honors its historic legacy while charting new directions under Artistic Director Dante Puleio.

A former company dancer appointed in 2020, Puleio carries forward the physical and emotional principles of the Humphrey-Limón technique while inviting new choreographic voices into dialogue with the company’s enduring repertory.

Limón’s dances continue to reveal the depths of the human condition, its gravity, resilience, and grace. In this interview, Puleio reflects on his vision for balancing preservation and reinvention, and on the company’s evolving place within the contemporary dance landscape.

Interview by Catherine Tharin

Let’s begin by discussing the Limón technique, one that is recognized as a foundation of modern dance. The Limón technique grew out of José Limón’s experience dancing with Doris Humphrey and Charles Weidman, who developed a ‘flowing' way of moving that depended on the gravity of weighted falling and recovering. Their technique expressed emotion through the movement itself. In what ways did Limón further this technique?

The Humphrey - Limón technique centers around the body’s relationship to gravity. The understanding of our body continues to evolve over time, but the dedication to the principles of breath and weight remains a constant. That combination serves the artists of each generation - how they interpret the work and how they are able to make it their own while staying true to the intention of both the technique and repertory.

In Humphrey’s work, Two Ecstatic Themes (1931), for example, she is literally falling and recovering. Two Ecstatic Themes is the first dance that I learned, but the dance There Is a Time (Limón, 1956), feels like the birth of the ways José brought the Humphrey technique into his world. The use of momentum was incorporated more. The pieces were originally titled Themes and Variations. In the theme of Ecclesiastes, José was physically working through a very simple folk movement structure with this idea of fall and recovery. As you move the feet in a grapevine, you're feeling the momentum of the community moving together. Inside that movement, you feel the fall leading to the recovery and that recovery leading to the fall in this continual pendulum. That's how it found its way into what we know now as the Limón technique. This work is based on principles, and that's the beauty of it. We discover the principles resonating in our bodies. There's a sense of evolution.

How has the technique evolved over successive generations?

I can step into classes taught by different teachers over decades, and it all has this element of ‘coming home.’ An example: Dr. Daniel Lewis, José’s protégé, came as a guest artist to the University of Florida, where I was teaching. I hadn’t taken his class in years, and in the meantime, I developed my own approach. I watched him teach and coach students, and I thought, ‘Oh man, we say the exact same things.’ He learned from José, and I learned from others, but we were emphasizing the same principles, just phrased differently. How we embody it may shift because of who we are as dancers and how society evolves. The technique reflects the human experience - our hope, our despair, and the refinement of our physical articulation. The dancers today are so finely tuned, asking questions I wouldn’t have thought to ask.

Can you give an example of new questions dancers are asking about the technique?

For example, we were exploring a succession from the shoulder - an internal rotation that goes from inside the right shoulder socket all the way out, then retracts through the elbow, wrist, and hand. They asked, ‘Where is that feeling coming from?’ We figured out that you feel it at the base of your scapula. You initiate from inside your scapula for the shoulder to start. The minutiae become more important because the level of awareness in their bodies is heightened. That level of awareness is part of the journey. They walk in with so much more information than we did.

When you pass on a role to a younger dancer, what aspects of the technique do you emphasize first-physicality, emotion, or both?

That depends on the piece and the dancer. If I know that a dancer usually comes at it from a specific place, then I’ll meet them first, either anatomically or emotionally. Sometimes I challenge them to get there through physicality on their own, versus telling them how to approach it. Other times, I start with intention - what is this character feeling? It varies from piece to piece. Honestly, it’s astounding how differently each dancer connects. I encourage dancers to inhabit the emotional truth, balancing fidelity to the choreography with their personal interpretation.

What roles are most memorable for you as a performer?

Impossible to narrow down, but Iago from The Moor's Pavane (1951), Carla Maxwell (former Artistic Director) gave me so much room to play, it was one of the first times I truly felt unleashed inside a Limón work. The ‘Just Man’ in Psalm (1967) was a role that, despite the abstract nature of the work, there was such inherent drama that I was able to pour all of myself into each performance. The piece wrecked me emotionally, and I loved walking off stage each time completely drained – I was never more alive. And finally, The Traitor (1954), it was such an intense performing experience that I feel like every performance of it is etched into my memory.

How do you maintain a fresh emotional connection to a work you’ve performed many times?

No matter how many times I’ve come back to a work, I can find another level of connection because the questions are open-ended about our human experience. No matter how many times I laugh, I’ll still laugh when something is funny. When something is sad, I’m still going to cry. Just because I’ve cried 100 times doesn’t mean I’m going to stop at 101 if I’m open to what I’m experiencing in the role.

I bring that to life, whether I’m responding to the artists around me or manifesting something inside myself. The journey becomes a very real one - to access how I can inspire that emotion in the dancer I’m working with, or what I need to feel from them to respond in a way that makes sense for the piece.

How do you identify emotional capacity in new dancers?

During auditions, we’re aware of the dancer’s emotional landscape. It’s part of that research. In Choreographic Offering (1964), for instance, a very physical dance, if they’re not vulnerable enough to take the risk to fall, then I generally don’t think that dancer is the right fit for this company. Being able to experience risk is foremost. The technique is an embodiment of human experience, so the physical and emotional are intricately woven. I don’t even know how to separate them.

How do you balance the original style of Limón’s work with contemporary performance practices?

This style of acting is so different now than when José created these pieces. At that time, actors were coming from the stage to the movie screen. Most emulated English actors who performed on stage, performed for the last row, even on camera - we’re talking black-and-white films. It’s a very different style of acting now. What we look to then may seem like overacting, but those are our origins. We have those conversations: where do we find the balance in this work? We live inside of those emotions that are the foundation of a dance. They become so present, so real, so visceral - it doesn’t feel like overacting. It feels absolutely real. That’s why we have to tap into who the dancer is as a person so they can access those emotions. In this way, we allow the piece to breathe. We’re not keeping it dated because we have to act as the dancers acted when the dance was created. The intention - what’s important - is the same. How would a person respond today? The goal is visceral, present emotions, never dated reproductions.

Do you notice generational differences in approaching the same work?

In the past five years as director, I’ve seen different versions of The Moor’s Pavane. I danced different versions, and it’s the same vocabulary. You shifted from night to night, from performance to performance, from rehearsal to rehearsal. The ending was always the same, but how we got there, the relationships, the approach, the energy, differed and the relationship between the two characters was different. Each new dancer brings their own personal experience to these themes. Seeing that come alive helps Logan Francis Kruger (Associate Artistic Director) and me, this is who they are, and this is how they're approaching the role. This is what they're bringing, so we mold or encourage them based on this assessment. The rules, the parameters, stay true to the story but also stay true to the artist who is performing.

For instance, Eric Parra, a Moor I worked with for the past couple of years, in the scene where Desdemona lies over his knee, he’s rocking her back and forth, and he is so heartbroken. With Pablo Francisco Ruvalcaba as Moor, it was another kind of heartbreak. Every time I watched him, I would just lose it. Now I'm watching Johnson Guo, and his approach to that moment is totally different. I get really scared when Johnson walks downstairs in a way that I didn't get scared with Eric. All are totally relevant to the story and make complete sense to who they are and how they bring the role to life, but what I feel from each of them is pretty different. I find this fascinating. The dancers live in the realm of acting, but it's the movement and the emotion that bring it there. It changes from person to person.

How is repertory transmitted in your company?

It’s so much about live experience. When José would restage a work, he sometimes changed it a little to get more out of the dancer. There’s this one story with Exiles where he changed a whole section. Danny Lewis asked, ‘Why did you do that? It looked so beautiful.’ And José said, ‘I could tell the dancers needed something made for them.’ We look back and there are a variety of versions of the pieces. Each time we reconstruct a work, we revisit decades worth of material and create a version that honors the past and what makes sense for the artists in front of us. There’s a buffet of options. After the reconstructor- often a dancer who has performed the role -sets the version, a soloist might, after watching old footage, say, ‘I really love what this performer did in 1967.’ We look at that and play with it. Let’s see why you’re attracted to that and how this choice affects the work as a whole.

What was the aesthetic journey for the commission by Kayla Farrish, a younger choreographer, for her new work created last year?

If there is a lost work and we don't have film footage, but writings, stories, and photos (we have plenty of that kind of ephemera for the lost works), then I will give the story, the photos, the research, and any writings to a new choreographer, and they'll create a work based on this archive.

José choreographed a dance on Mexican dancers in Mexico City and returned to the States to rechoreograph the dance that he then retitled. There’s no film footage. Last season, Kayla Farrish was given photos and the story, and we said, “Be inspired.” José was working through this idea of a community coming together despite obstacles. She worked from that and created a new dance titled, The Quake that Held Them All (2024). Contemporary choreographers can engage with José’s works that are lost by using the archives. It's very rich.

What is the company’s role in contemporary dance today?

We have a huge international platform. The company was the first to act as a U.S. ambassador for the arts in any medium, touring around the world. Those works continue to live, breathe, and make sense. We still reach people. We also commission choreographers early in their careers. I curate programs that support that premiere. For example, I wouldn’t put Missa Brevis (1958) next to a very young choreographer, but I might pair it with an Azure Barton work. There Is a Time could be put next to an Akram Khan work. That creates bridges across time. José’s lesser-known earlier works are put in dialogue with emerging voices, with someone like Kayla, a choreographer who has an incredible voice and will have a phenomenal career. I want to make sure that the Limón work supports a young choreographer’s work and that it isn’t compared to these humongous Limón works that have spanned 80 years. This approach creates a supportive platform for artists at different points in their career.

Can you speak about the 80th anniversary performances at the Joyce Theater?

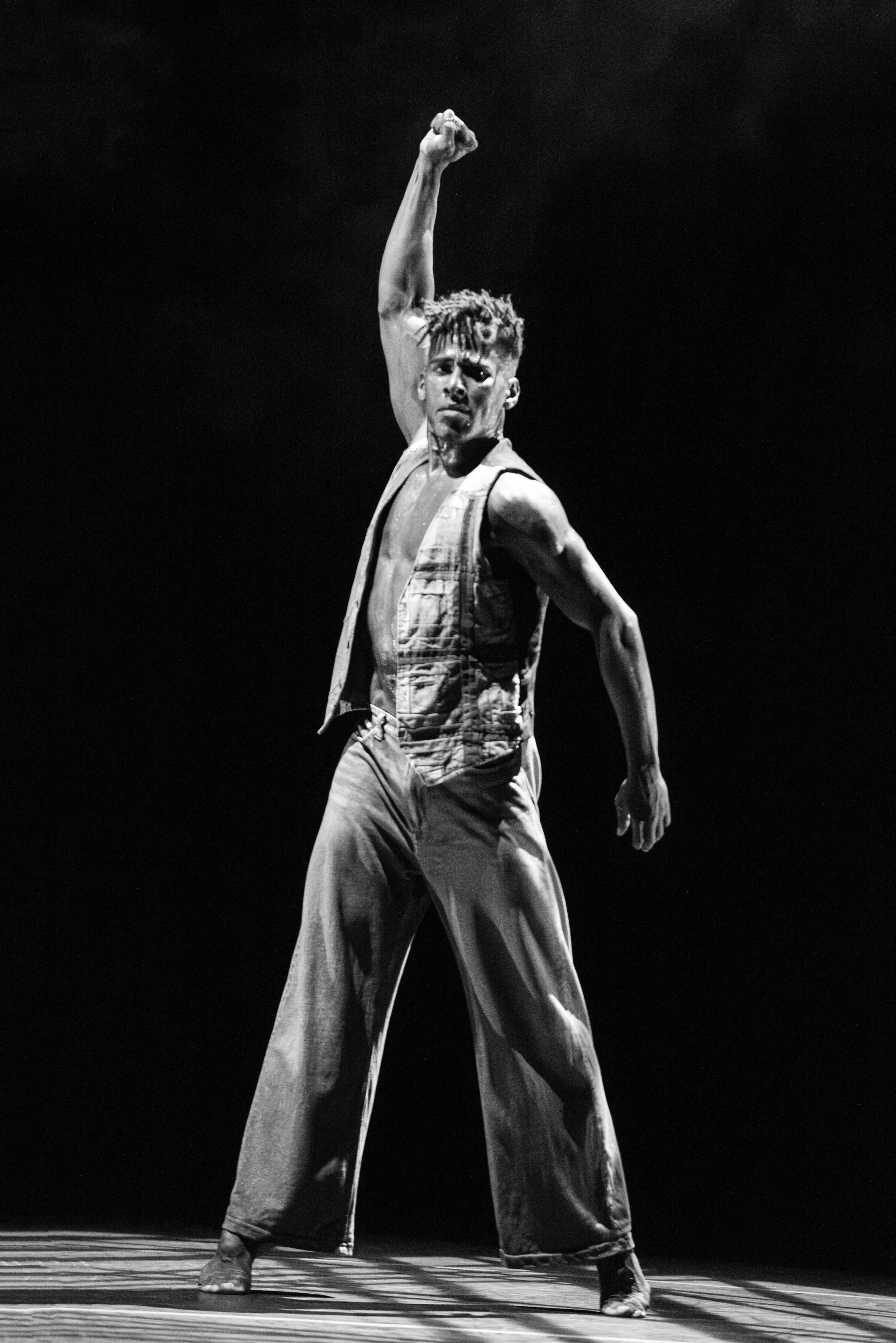

We’ll perform Chaconne, one of José’s earliest and most iconic solos, created to show that men could dance and had a place in modern dance. That was a big deal in the 1930s and 40s. Men belong in modern dance, and it’s still important to show that visibility and power on stage. For the 80th anniversary, we're presenting a multi-generational group version of Chaconne with 20–25 dancers, from people who danced with José himself to students from LaGuardia Performing Arts High School experiencing Limón for the first time. We’re handing the baton from generation to generation. It’s a moment of family and community.

We’re taking The Emperor Jones off a Caribbean island in the early 1900s and putting the dance squarely in Manhattan, 2025. Instead of the jungle, now it’s our city. New intentions underlie each section. The choreography remains the same, but costumes, lighting, and set offer a contemporary reframing, exploring capitalism and current power dynamics. I’m looking at where we are in the world today. There’s an undercurrent of commentary about leadership. There’s also homoeroticism between the two main characters, which leads me to a commission by Diego Vega Solorza. For the 80th anniversary, it feels right to honor a Mexican choreographer. Diego is from the same area of Mexico as Jose, so bringing the two artists on the same stage, who had similar upbringings but respond to the world in strikingly different ways, feels like an important moment at the 80th anniversary. Vega Solorza brings the dance, Jamelgos, that explores male identity and queerness.

Please comment on the veiled queerness in Limón’s works.

I'm really interested in what we don't know about Jose, or what has been kind of open but not talked about. José had all of these works with two men as male protagonists and male antagonists. Dances are autobiographical, whether you intend them to be or not, so I'm wondering why he was working with this constant resurgence of male power. It’s subtle, but it’s there.

How are you honoring Carla Maxwell during this season?

This season is dedicated to Carla Maxwell, who was artistic director for 40 years. She was the director when I was a dancer. She took the company from a time when all the modern dance legacy companies still had their founders—Paul Taylor, Martha Graham, Merce Cunningham. They were still alive, still networking, having Halston make their dresses. They were building their names. José died before networking. Carla made a road map for how this (bringing a company forward) can be done after the founder dies, and every company has followed her lead. She laid the groundwork for what I can do now. She managed to lead the company while being a dancer decade after decade. There’s no better way to honor her than by dedicating this season to her.

You seem like the ideal person for this time in the company’s history.

I hope that when I hand it off, the company is healthier than I found it. My goal is to honor the past, support the present, and set the stage for future generations. Then I will have done my job.

All photographs by Kelly Puleio

Did you like what you read here? Please support our aim of providing diverse, independent, and in-depth coverage of arts, culture, and activism.

CATHERINE THARIN choreographs, curates, teaches, and writes. She danced in the Erick Hawkins Dance Company in the 1980s and '90s, was the Dance and Performance Curator at 92NY, NYC, for 15 years, and was a senior adjunct professor at Iona College, New Rochelle, NY, for 20 years. She writes dance reviews and articles for The Dance Enthusiast and Side of Culture, reports on dance for WAMC/Northeast Public Radio and writes about performance for the New Pine Plains Herald. She has contributed to the Boston Globe. She programs dance at Stissing Center, Pine Plains, NY and dance movies at the Millerton (NY) Moviehouse. Says Fjord Magazine of her work: 2023 - "The evening was consistently charming, well-crafted and paced." 2025: "Her witty series of dances explores romance and its complications.”