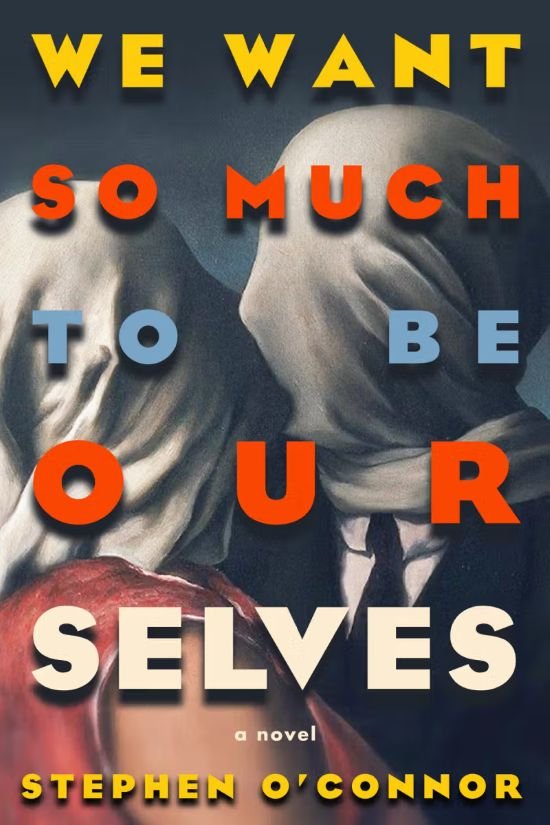

Complicity, resistance, & love in the face of evil: Stephen O'Connor on his forthcoming novel WE WANT SO MUCH TO BE OURSELVES

Photo by Angela Cappetta

STEPHEN O’CONNOR is the author of seven books, including two novels: We Want So Much to Be Ourselves, (forthcoming from Bellevue Press) and Thomas Jefferson Dreams of Sally Hemings; two short story collections: Here Comes Another Lesson and Rescue; Quasimode, a collection of poetry; Will My Name Be Shouted Out?, a memoir of his eight years teaching in a New York City public school, and Orphan Trains, a history of a controversial nineteenth century child welfare effort.

His fiction has appeared in The New Yorker, Harper’s, Best American Short Stories, and many other places. His story, “Ziggurat,” was read by Tim Curry on Selected Shorts. His poems have appeared in Poetry Magazine, Conjunctions, The Beloit Poetry Journal, and elsewhere, and his nonfiction has been in The New York Times, The Nation, Agni, and The Boston Globe. He teaches creative writing at Sarah Lawrence and lives in New York City.

Interview by Tyler Nesler

We Want So Much to Be Ourselves features so many clear parallels to what is happening in the U.S. today and the horrific political realities of what led to the rise of Nazism in 1930s Germany, which bolsters the book with an immediate timeliness. However, the book will not be officially released until June of 2026, and it's difficult to predict how much worse the situation could be here by then.

As an author of several traditionally published books, I'm sure you've learned to be patient through the often-lengthy process of publication, but in this case, is the urgency of the present situation testing that patience? Considering the pressing nature of these matters, do you feel especially impatient for this book to be out in the world compared to your past works, and if so, how are you dealing with it?

I am VERY impatient! But that said, Erika Goldman, my editor at Bellevue, feeling a similar impatience, has accelerated the publication schedule, so that the book will come out four months before the midterm elections, thus making it at least possible for the story it tells to have some effect on public sentiment. Every other book I have ever published has come out more than a year after being sold to a publisher. This one will be coming out ten and a half months after its sale, and Erika’s willingness to do that was part of what made me eager to go with her press. I would, of course, want the book to come out even sooner, but positioning a book so that it gets maximum attention from reviewers and the reading public simply requires a lot of time, and without such attention my book would be incapable of having any effect.

Despite my current sense of urgency, I began the book in the summer of 2016, at a point when I thought there was no chance of Trump’s being elected. Initially I was primarily interested in exploring how psychoanalysis (“the Jewish science”) fared during the Third Reich, especially since one of psychoanalysis’ central tenants—that all “truths” must be questioned, especially those deemed unquestionable—is radically opposed to any authoritarian regime’s absolute requirement that its own dogma, no matter how illogical or fact-free, be accepted as the one and only “truth.” The emotional core of the novel, as I first imagined it, would be my psychoanalyst protagonist Günter Zeitz’s struggle to maintain his virtue in a totalitarian state, his love for his brilliant, but psychologically damaged wife, Josine, and their daughter Hannah.

It was only once Trump was actually in office that I began to think about the deeply disturbing parallels between his policies and those of Hitler, although, even then, I didn’t think of my story as primarily a critique of Trump’s brand of fascism. Mainly I thought that, because WE WANT SO MUCH TO BE OURSELVES also chronicles, step by step, the process by which Hitler appealed to the very worst instincts of the German people through grotesque lies, and crushed his opponents by threatening, imprisoning and killing them, it would be impossible for readers not to see novel as a commentary on the worst possibilities of Trump administration, even if that was not the book’s primary focus. I finished the novel during the final summer of the Biden administration, at which point I very definitely feared that Trump would be reelected, but did not yet know how fiercely and rapidly he would pursue his fascist agenda.

Ironically, one of the points my title alludes to is how the advent of a pernicious political regime can change one’s sense of one’s own character. Günter is compassionate, wants to help people, and is always willing to see the other person’s point of view, traits that are clear virtues under normal circumstances, but that were the road to Hell in Nazi Germany. In a similar way, practically since day one of Trump’s second term, I have come to feel that the political commentary of my novel has become its most important element, though it is still very much about my characters’ struggles to love and be loved.

Bellevue Literary Press

An excerpt version of the novel, The Interpretation of Dreams, was published in Harper's in 2020. Could you discuss how this story introduces the book's central themes and characters? How do its elements now differ from the completed novel, and what makes it a good "appetizer" for readers interested in reading the whole book?

The Interpretation of Dreams is a compilation of excerpts from the first third of the novel. My goal when I put it together was simply to create an intriguing and emotionally engaging story that would work in its own right, though, of course, I did hope that its appeal might stimulate interest in the novel when it finally appeared. The story opens with what is now the beginning of the second chapter, when Günter accosts Sigmund Freud on the street in Vienna in the hope of being invited to study with him. Although the story also includes Günter’s first meeting with Josine, a patient of Freud’s, it is primarily about a philosophical disagreement between Günter and his mentor. Near the end of the story, Freud tells Günter about an argument he had with Rilke about the nature of “the Eternal,” which Rilke saw as a manifestation of the Divine, whereas to Freud, an atheist, the Eternal was, as he explains to Günter, simply the universe’s absolute indifference to humanity and human values, a state of being that makes the Eternal so “unconditionally itself, and so magnificently heedless of any idea we might have about it that it feels like pure freedom. And so, it is awe-inspiring and profoundly beautiful—the only thing in all of creation that we can truly love. But still,” Freud continues, “the most important thing about the Eternal, is that we can’t help but perceive it as cruelty. And so the love it inspires in most people takes one of two forms: either we make ourselves abject before the Eternal, in the hope that it will not destroy us—which is to say that we worship it. Or we attempt to take the eternal into ourselves—which is to say that we make ourselves the agents of its cruelty.”

In this speech, Freud renders both the novel’s moral universe and two ways of responding to that universe that are, I hope, clearly germane to the philosophical and emotional predispositions of the Third Reich and Trump’s second term. Immediately after this discussion, Günter has a dream in which a third way of responding to the universe’s indifference is suggested: that, as implacable as it may be, we can also resist it by asserting the value of our humanity and the necessity for compassion and justice. While the philosophical argument conducted in WE WANT SO MUCH TO BE OURSELVES is much more complex, these three responses animate the whole novel, and they are what I most hoped my Harper’s excerpt would suggest to readers.

Freudian psychoanalysis is a foundational element of the novel, exploring, as you've written, the "nature of the self and of self-deception, love as both a source of strength and weakness, and, maybe most important of all, Freud’s notions of the life and death drives as they relate both to love and to fascism."

Freud's work has a complex legacy, with many of his ideas still influential but now also apparently considered unscientific or untestable. However, what do you think are some of his core foundational concepts that are still relevant, especially within the context of what is unfolding in America today?

Perhaps I should begin by saying that my father was a Freudian psychoanalyst, and so I grew up in a home where Freudianism infiltrated almost every idea I had of myself and the world in which I lived—and far from always in ways that benefited my mental health!

For more than half of my childhood, I had no idea what my father did for a living. Initially he told me that he was a “head doctor,” which I interpreted as meaning he put bandages on people’s skulls. Later he told me that he helped people with their emotional problems, but I couldn’t figure out what an “emotional problem” might be, nor how a doctor might “cure” such a thing. But then one day, when I told my father about a middle school friend whose behavior had upset me, he said, “Most people don’t know why they do what they do. So, if you want to know who your friends really are, don’t listen to what they say about themselves, just pay attention to what they do.” That explanation had a revolutionary effect upon me. Not only did it suggest that my father “cured” his patients by getting their image of who they were closer to who they actually were, it made me a lifelong skeptic of people’s rendition of themselves, including my own. That skepticism is founded, of course, upon the Freudian notion of the disconnect between the conscious and unconscious minds, a notion whose validity still seems self-evident to me and very important. But the notion that has turned out to be most significant in regard to my novel and my understanding of both Nazi Germany and contemporary America is the concept of the death drive.

Before I say anything more on this topic, I want to make clear that the Sigmund Freud in my novel is a fictional character, who should not be confused with the historical Freud. Likewise, though I express ideas drawn from Freud’s work, they primarily serve the needs of my narrative and so reflect my own ideas at least as much or maybe even more than his. So: Freud sees the life and death drives as antithetical, with the former consisting of all the instincts impelling us to seek pleasure and do everything necessary for the propagation and survival of our species, while the latter serve to correct the excesses of our pleasure-seeking.

Freud often refers to the death drive in his discussions of guilt, and that has always made sense to me, though the notion of guilt as a drive toward literal death has always seemed over the top. But the more I researched, thought and wrote about the German people’s state of mind during the Third Reich, the more I came to feel that my rejection of the death drive had been naïve and that Freud’s rendition of the drive’s most excessive manifestations shed considerable light on both Nazi Germany and the Trump era.

During Freud’s cranky and ill-received toast at Günter and Josine’s wedding, I have him first celebrate their love as a manifestation of life drive, then go on to explain that, “while pain may be an inevitable consequence of seeking pleasure, it is always inadvertent and unwitting. Whereas pain is a primary mode of the death drive, as are hate, fear, anger and shame.” His speech concludes with his assertion that there is a good reason for the death drive being called by this name, "one that is, perhaps, particularly obvious during the present era, when an ever-growing number of people, inspired by a fanatic, are animated only by hate, fear, anger and shame. We are fortunate that, thus far, these would-be agents of the death drive seem unable to take their collective neurosis to its logical conclusion. But we would be fools to imagine them incapable of doing so. And I fear, gravely, that our ability to avert such a catastrophe may be rapidly diminishing.”

You are striving for complexity with both psychology and personal identity in this book, rather than presenting "heroic resistance fighters or camp survivors who overwhelmingly predominate Holocaust literature." What were some of the challenges you faced in going against the grain of this genre? Was it difficult to sell a story of nuance compared to a more black and white, good/evil binary thinking dominating the current political and social discourse in the U.S.? How do you hope it will help readers better understand the resentments and grievances currently brewing on all sides of the spectrum?

One reason that the stories of camp survivors and resistance fighters so predominate Holocaust literature is simply that the stories of those who did not survive or resist are so depressing. The problem with this obvious fact is that the Holocaust stories that leave us with a sense of redemption tend to concern only a tiny sliver of the total population caught up in that grim era.

When I first started working on my novel, I felt that it was essential to explore the hearts and minds of the vast majority whose lives had no redemptive conclusion, as, without doing so, we could neither grasp the true nature of the Holocaust nor be able to protect ourselves against its recurrence. In the end, my desire for my book to help avert such a recurrence was my most productive source of inspiration, which is not to say that I was fully aware of the nature and implications of scenes and ideas that flooded my brain. All I knew was that I wanted to explore the motivations and experiences of a fundamentally “good” German who would nevertheless become morally implicated in the Nazi horror, a moral territory that has long had a hold upon my imagination. For reasons that I don’t entirely understand almost all of my fiction concerns people who are simultaneously good and evil—with Thomas Jefferson, one of the two protagonists of my last novel, THOMAS JEFFERSON DREAMS OF SALLY HEMINGS, being the most extreme example.

As I started taking Günter Zeitz year by year, event by event, from Hitler’s rise to prominence in the mid-1920s through most of the Third Reich, I began to understand how, a mix of selective attention and self-deception in conjunction with the Nazis’ significantly dog-whistled rendition of their intentions, the fact that no one knew the Holocaust was even possible and the multiple forms of terror that Hitler evoked in everybody under his influence had made it possible for Germans to, in fact, simultaneously know and not know of the evil in which they were all complicit. This state of mind absolutely fascinated me and so, alas, dominated my presentation of Günter in the draft of the novel that my agent first submitted to publishers. It wasn’t until that draft had accumulated several rejections that I realized I had created everybody’s nightmare of who they might have been in Nazi Germany, and so had written a book that only masochists would want to read. Clearly, if my book was ever to get published, I would have to revise it substantially.

I was determined not to ameliorate Günter’s character by turning him into a courageous resistance fighter, though I had already had him inadvertently resist the Nazis twice. But then, after much thought, it occurred to me that, although I believed Günter to have many redeeming characteristics, I had given them scant attention in the draft I had submitted to publishers. Not only did this mean that my original incarnation of Günter did not evoke remotely the sympathy in readers that I felt for him, but, more importantly, it meant that my book did not render an essential truth of the Holocaust, which was that it occurred in the midst of ordinary life, that as the evil we now associate with Nazi Germany loomed and intensified, people fell in love, had babies, went to work and school, suffered losses, enjoyed triumphs and were generally preoccupied with the sometimes trivial and sometimes monumental incidents of their quotidian lives.

Once I understood both these lacunae in my original version of the novel, it was clear that I had to render more of Günter’s troubled love for Josine and of his tranquil love for their daughter, Hannah, and more of his relationships with his patients and colleagues, including with Elke Weber, who would become his second wife. If I could pull this off, not only would Günter become more sympathetic and my rendition of Nazi Germany more authentic, but as my readers found themselves identifying with Günter even as they condemned him, they would be experiencing something very like his own moral challenges, and would have to work hard to arrive at a just evaluation of his character—exactly the sort of thinking I most want to inspire in readers. The revision seems to have worked well enough to have found a publisher. Now we will see what readers decide.

WE WANT SO MUCH TO BE OURSELVES will be available June 9, 2026.

Check out our other recent author interviews

Tyler Nesler is a New York City-based writer, editor, and podcaster. He is the Founder and Editorial Director of INTERLOCUTOR Magazine.

Did you like what you read here? Please support our aim of providing diverse, independent, and in-depth coverage of arts, culture, and activism.