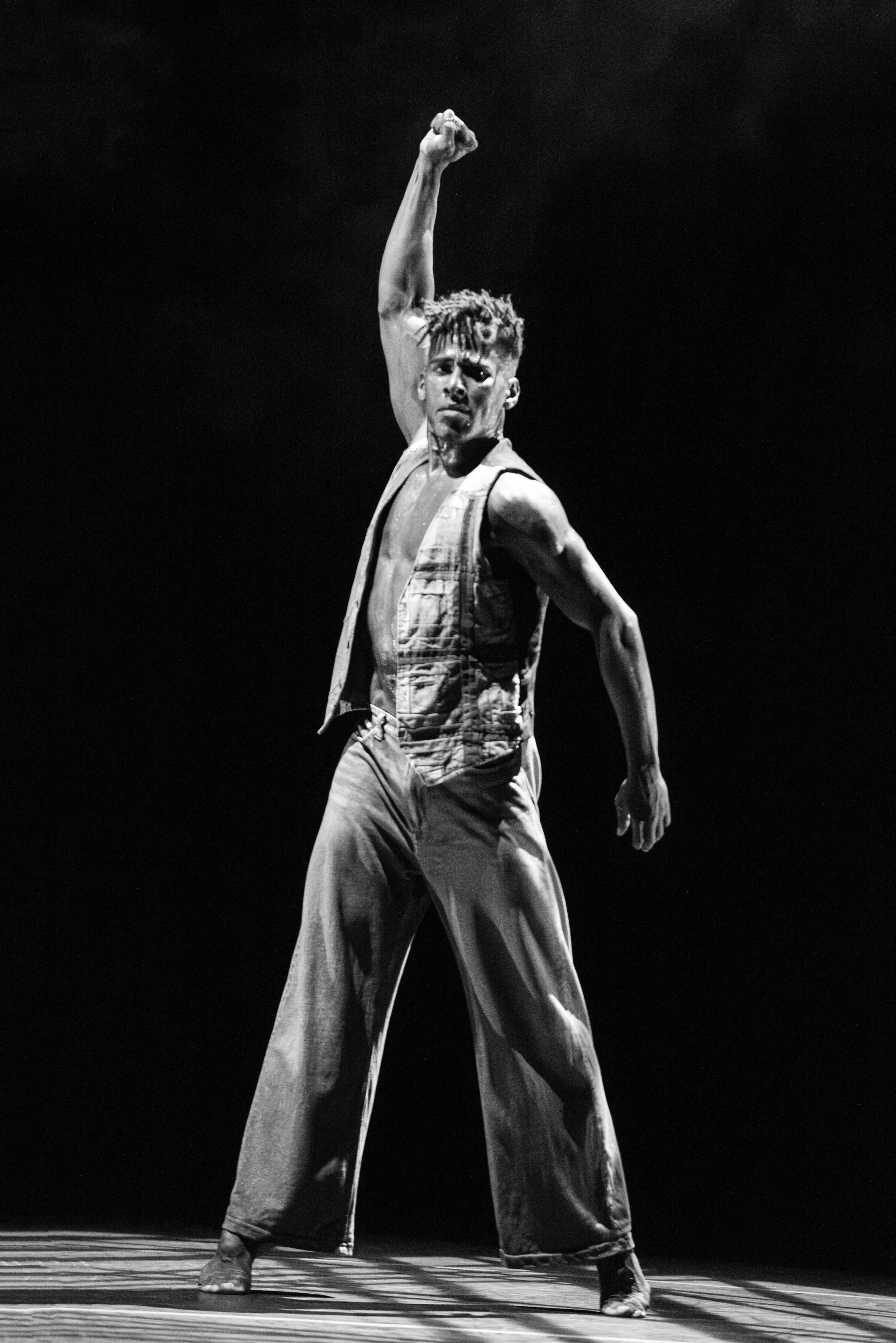

Dancer & choreographer MARK MORRIS reflects on his programming choices, artistic evolution, & what keeps him inspired

Photo by Beowulf Sheehan

Celebrating their 45th anniversary, the Mark Morris Dance Group has distinguished itself through Morris’ deep affinity for musical structure, wit, and formal invention. The legendary choreographer has long championed live music and musical rigor in dance.

As he returns to the Joyce Theater from July 15-26, with a repertory program that includes early work, lesser-seen gems and two New York premieres, Morris spoke about his programming choices, his artistic evolution, and what keeps him inspired.

Interview by Catherine Tharin

This anniversary program spans four and a half decades. How did you choose what to include?

I like contrast. Some pieces are old, some are new, and they look really different from each other so there is range and variety. I don’t like going to a program and everything seems like it could be the same piece.

We went over many possibilities of what pieces to include—some we left out, and others I decided to add at the last minute, meaning a couple of months ago. The biggest dance has ten people because that’s all there’s room for on the Joyce stage. We’re constrained by the limitations of the Joyce — no pit, no fly space, no crossover. So, I program accordingly. The music in this season is mostly chamber-sized: string quartets, solo piano, solo violin. That’s what fits, and I like it.

The programming is very carefully chosen - I almost said “curated,” but I’m glad I didn’t. It’s a variety pack. Two very different programs. Everybody has to see both of them.

You’re presenting two premieres. Please tell us about the first.

It’s a piece called Northwest, set to music by the renowned composer John Luther Adams. His music was a revelation to me the first time I heard one of his gigantic pieces. His thing is global - climate change - Anthropocene themes. The music he writes (thank God) doesn't sound political, but it is political. It is so, so complicated.

The piece that made me lose my mind was Inusksuit at the Armory in NYC with 100 musicians. You walked around like all the very skeptical New Yorkers, and I ended up like a lot of people just lying on the floor for an hour. And then I was sobbing. John Luther lived in Alaska for nearly 40 years and was friends with the people who lived there, a lot of whom were indigenous. He reverently learned the music. This is as close as you can get to writing it down.

I’ve choreographed five of his Yup’ik Dances and some of the Athabascan Dances. I’ve never heard of them being played in concert, so that’s one reason I want to do it. It’s like nobody’s heard of this. They’re based on games - juggling and skipping rope. They're like the theme songs of play and are a big part of the culture and they're really, really interesting musically, unpredictable and rhythmically fascinating and almost all the dances are done with feather fans. We use paper fans. It’s exciting and interesting and fun. It’s its own logic, this dance. And, played on the harp. It’s called Northwest because it’s from the Northwest.

For me John Luther’s work is magical. He really has something astounding. He always threatens it's gonna be his last piece but who doesn't do that?

Northwest - studio rehearsal, June 2025 - photos by Danica Paulos

And the other premiere.

In contrast, You’ve Got to Be Modernistic is set to this incredible James P. Johnson stride piano piece. It’s based on the left hand in 4/4 time - boom chick boom chick – that you're just throwing back and forth all night. And then on top of that is unbelievably complicated crazy gorgeous ornamented, confusing rhythms (with the right hand).

Johnson’s improvisation was so shockingly great. He never played the same way twice, and a lot of his stuff is just on piano rolls. Ethan Iverson transcribed it from a recording and he’s playing it live. He's been working on this for years and part of the reason is he wants other pianists to be able to play it. It’s super rhythmic and tricky—it really swings. The dance is fast and tight, but also kind of cheeky.

I’m not copying the music, but I’m absolutely working with its phrasing and accents. Working with Johnson is like, “wow,” you've set yourself up for something that's super difficult.

You've Got to Be Modernistic - studio rehearsal, June 2025 - photos by Danica Paulos

Ethan Iverson - photo by Beowulf Sheehan

You’ve always insisted on live music. Why is this essential for you?

If you’re dancing to music and the music is not there live, it’s not music. The air is dead. You’re faking it. I never use recorded music in live performance. Never have, except for Going Away Party (1990), we use a recording from the 1970s, the last recording that Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys made before he died.

I love that recording — it’s exquisite, full of the sound of those old guys singing. It’s alive and vibrant in a way you don’t get from earlier versions from the ’30s or ’40s. I worship country western music in general and western swing in particular, so it’s a perfect fit. Because of the practical limitations of the Joyce — we can’t have a live band of that size — we use this recording.

Going Away Party

Tell us about the other dances on the program.

One of the early ones is Ten Suggestions, from 1981. It was originally a solo for Peggy Baker and was performed by Misha (Mikhail Baryshnikov). It’s set to Tcherepnin and is very improvisational, so nobody does it the same way twice. Dallas McMurray has done it recently with us and it’s just a beautiful piece.

Then there’s Silhouettes (1999), a duet originally for two men, former San Francisco Ballet dancers, created for their ballet company in Florida. I allow ballet companies to do that piece if they buy it. There’s The Argument from 1999, and The Muir, set to Scottish folk songs.

Ten Suggestions - Gainesville, 2013 - photos by Ani Collier

Silhouettes - Gainesville, 2013 - photo by Ani Collier

The Argument - studio rehearsal, June 2025 - photo by Danica Paulos

How does a piece like The Muir (2010) come about?

That was a commission from the Edinburgh Festival, for Hogmanay—New Year’s Eve. It was supposed to be a celebration of all things Scottish. And I thought, well, I’m not Scottish, and neither was Beethoven, so I feel qualified. He didn’t speak English either.

Beethoven arranged a lot of British music—Scottish, Irish, English. So, I took the Scottish ones and made this piece. It’s not Scottish in any authentic way. But it’s beautiful, and I wanted some vocal music on the program. That’s as Scottish as I’m going to get.

The Muir - Dance Center, 2011 - photos by Richard Termine

What about Mosaic and United (1993)?

That’s one of my favorite dances. Like children, I’m not supposed to have favorites, but I do. It’s set to two distinct string quartets by Henry Cowell, who was a genius. I made it for my company and for White Oak back when they were only performing my work and included Misha, Rob Besserer, and Kate Johnson.

Either five people or ten people perform the work. Originally it had five of my dancers and five of theirs. We’re doing the ten-person version at The Joyce. It’s big and exciting and sounds amazing in that space. It’s always a revelation.

Mosaic and United - Philadelphia, 2018 - photos by Beowulf Sheehan

You teach company class regularly. What does that look like now?

I teach three times a week now. It used to be five. It was zero during COVID when I thought I was gonna lose my freaking mind. I lost the ability to cook or read or learn Italian. I was really stuck. It took me a while to come back. Now three days of class, and then we rehearse for a healthy four or five hours. More than that doesn’t work.

I teach a full ballet class every time — very anatomically appropriate and musical. My favorite teacher was Marjorie Mussman. I studied with her as a teenager in Seattle and then in New York. She taught at my building in Brooklyn until she died. I learned everything from her. That’s the legacy pedagogy as far as ballet technique goes. I agree with her placement entirely. I took Jocelyn Lorenz's class, too. That's how I knew people from ABT and Merce and Paul Taylor. Everybody took those classes.

Do your dancers always take your class?

They’re required to take my class. We have physical therapy on-site, and they’re taken care of very well. My dancers aren’t kids — they’re in their 20s through 40s — so it’s a different kind of maintenance to stay physically healthy and able to do this job.

What do you look for in a dancer?

They have to be smart. They don’t all have to read music, but they have to be able to hear it. I can teach them phrasing, but I can’t teach them how to think. They have to come in with that.

How long do dancers usually stay with your company?

I’ve had dancers who’ve stayed for 20 years. That’s rare. But when it happens, it’s wonderful. The work gets deeper. They know what I want before I say it.

Do you start with the music when you make a dance?

I start with the music. Always. I find it, I listen to it a million times, I learn it – I mean really learn it – and then I start making the dance. That’s the process.

You’ve worked with a range of composers. How do those collaborations unfold?

When I work with composers, I don’t ask for anything specific. I just say, write what you want. And when it’s done, I’ll choreograph to it. I don’t work with pieces-in-progress and MIDI files or anything like that. I need the whole piece. Finished.

Does revisiting your early choreography feel like confronting a younger version of yourself?

Sure, it’s like a time capsule. I look at it and I think, oh, that’s what I was working out then. But I don’t feel nostalgic or anything and I still agree with a lot of those choices.

Your choreography is often described as musical, witty, and formally rigorous. Would you say that’s accurate?

I like formality. I like counterpoint and repetition and canon and all those things. I like rules. I’m not making it up as I go along. I work within a structure. But it’s not a math problem; it has to be fun to watch. I’m funny, okay? That’s just how I am. If you don’t like that, you’re not going to like my work.

Do you still attend performances?

I go out a lot. I consume culture and I produce it, so that's my job. I go to see stuff if it looks good. I’m not going just because I’m supposed to. I go to a lot of opera. I like going to something where I might be surprised.

There’s some dancing that’s really good that’s going on—there’s just not a lot of it and hard to find sometimes. I saw Ephrat Asherie’s piece DiaGenesis. Ten musicians onstage, fabulous music. It was the best dance I’ve seen from her, and she danced in it. It was just great.

I'm going to ABT to see Gillian Murphy's retirement performance because she's a genius.

You’ve been outspoken about dance trends. What do you think of the current scene?

Too much boring dance. People pretending to be profound. Everyone seems to be making the same piece – slow, vague, full of heavy breathing. It’s exhausting. Some people make work that’s just deliberately obscure, and you’re supposed to admire it because you don’t understand it. I think that’s nonsense. Everybody wants to make work that’s important. I’m not interested in important. I’m interested in good.

What should dance be instead?

Dance should be alive. It should mean something. That doesn’t mean it has to have a political message or a story. But it should be clear and intentional and have something to say - through form, through movement, through sound.

And other trends?

A lot of the foundations aren't giving money to performing arts, and it's very, very rough. It always has been. It’s true that not too many people are interested in (contemporary dance) so we've been fighting for that and trying to put on good shows because that's the job. Really, I'm an entertainer.

How do you stay inspired?

There’s always another piece of music to get excited about. I still love rehearsal. That’s the best part – figuring it out with the dancers, building it up. I’m not tired of it. The audience is important, but I don’t make work for them. I make it for rehearsal. If it’s still interesting after 400 rehearsals, then we show it to people.

Do you ever think about legacy?

I don’t think about legacy much. I want my company to keep going after I’m gone. I want the dances to be done right. But I’m not planning a museum.

Any advice for young choreographers?

Learn music. Learn how dance came to be what it is. And don’t be so precious. Make things. Lots of things. That’s how you learn. And if the audience doesn’t like it, maybe fix it. Or make the next one better.

The Mark Morris Dance Group’s 45th anniversary season program runs from July 15 to July 26 at the Joyce Theater in New York. Click here for tickets and full program details.

Did you like what you read here? Please support our aim of providing diverse, independent, and in-depth coverage of arts, culture, and activism.

CATHERINE THARIN choreographs, curates, teaches, and writes. She danced in the Erick Hawkins Dance Company in the 1980s and '90s, was the Dance and Performance Curator at 92NY, NYC, for 15 years, and was a senior adjunct professor at Iona College, New Rochelle, NY, for 20 years. She writes dance reviews and articles for The Dance Enthusiast and Side of Culture, reports on dance for WAMC/Northeast Public Radio and writes about performance for the New Pine Plains Herald. She has contributed to the Boston Globe. She programs dance at Stissing Center, Pine Plains, NY and dance movies at the Millerton (NY) Moviehouse. Says Fjord Magazine of her work: 2023 - "The evening was consistently charming, well-crafted and paced." 2025: "Her witty series of dances explores romance and its complications.”