An interview with VANGELINE, artistic director of the Vangeline Theater/New York Butoh Institute

Vangeline - photo by Matthew Placek

Vangeline is a New York–based teacher, choreographer, and dancer specializing in Japanese Butoh. As the artistic director of the Vangeline Theater/New York Butoh Institute, a leader in the development of contemporary Butoh dance since its founding in 2002, the institute offers public Butoh classes, workshops and performances. Vangeline is widely recognized for her rigorous, research-driven approach to Butoh and for expanding the form’s relevance in the 21st century. She carries forward the legacy of Butoh while infusing it with contemporary relevance—through activism, research, and performance.

New York Butoh Institute Festival, which uplifts the work of women in Butoh, and Queer Butoh, a festival centering LGBTQ+ voices within the form were both founded by Vangeline. She is also the visionary behind The Dream a Dream Project, an award-winning program now in its 18th year that brings Butoh to incarcerated individuals in correctional facilities across New York State.

Vangeline is the author of the critically acclaimed book Butoh: Cradling Empty Space, which delves into the connection between Butoh and neuroscience. She led the first-ever scientific study measuring the effects of Butoh on the brain (The Slowest Wave) for which she received a 2022 National Endowment for the Arts Dance Award.

Vangeline’s choreography has been presented internationally in Chile, Germany, Italy, France, Finland, Denmark, the UK, Mexico, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan. Her work has been widely acclaimed, both nationally and internationally, with critics praising its power, precision, and emotional resonance. She is currently premiering MAN WOMAN, a new Butoh duet in collaboration with Akihito Ichihara of the world-renowned Butoh company Sankai Juku.

Interview by Catherine Tharin

Butoh emerged in post-war Japan and is often associated with darkness. How do you connect with its origins while making it resonate with contemporary audiences?

As a French artist who has trained extensively with Japanese masters and now works and lives in the United States, I see myself as a bridge—linking cultures, histories, and generations within Butoh. While I’ve trained for nearly two decades under Japanese teachers, the art form itself has always been the result of cultural cross-pollination.

From its very beginnings, Butoh was shaped by artistic encounters across continents. In the early 20th century, Hirobonu Oikawa traveled to France to study French corporal mime and ballet with Etienne Decroux. He brought these art forms back to Japan, influencing contemporaries like Kazuo Ohno and Tatsumi Hijikata—considered the founders of Butoh. Later, in the 1950s, Tatsumi Hijikata and Yoshito Ohno (Kazuo Ohno’s son) were profoundly impacted by Katherine Dunham’s performances when she visited Tokyo, and they were equally awe-struck by Marcel Marceau, the legendary French mime-poet who made the unseen visible. These encounters and exchanges permeated the foundations of Butoh, embedding cross-cultural dialogue into its DNA. Later on, in the late 70s, there was a Butoh exodus from Japan—many second-generation Butoh practitioners live in Europe today.

To make the art form resonate with contemporary audiences today, we only need to remain within this lineage—this traditional trajectory of cross-cultural encounters. Each practitioner brings their own heritage and embodied history to the art form. In my case, that includes my French roots, my early background in ballet and jazz dance, and my experience as a burlesque performer. Interestingly, many early Butoh dancers in Tokyo also had ties to erotic and burlesque dance—sometimes out of necessity, sometimes as artistic rebellion—so this influence has been embedded in the form since its inception.

I work with people in Chile, in Taiwan, in Latin America, in Europe, and everyone comes into this encounter with their cultural heritage, their DNA, their biographical history—but also beyond biography, with all we carry as human beings that extends far beyond our own individual lives. We are each a link in a much larger human chain. Butoh helps us embrace that bridge phenomenon, connecting across cultures, ancestries, and unconscious legacies that live within the body.

Butoh is not meant to stay frozen in time or preserved in a museum. It evolves when artists engage with their communities and the times they live in. That means the art form remains relevant when those who practice it redefine it in the making, while being embedded in a community and a specific moment in time—offering classes, workshops, and performances that truly engage with people. We remain relevant when we engage, quite simply, with our community and with the era we are living in.

How do you approach the global reach of Butoh while maintaining its lineage?

Every practitioner brings their own history, lineage, and heritage. My approach is to honor the lineage while adapting to the cultural context of each community I work with. This is a living, breathing practice.

I work globally, and each encounter is unique. Workshops in Chile are different from Taiwan, from Europe. People come with their cultural DNA, their body memory, and their life history. Butoh helps connect those threads, bridging across cultures and generations.

You’ve often placed Butoh in unexpected contexts, from nightclubs to site-specific performances. How does working in these spaces shape the art form?

This is why I’ve always sought to place Butoh in vibrant, unexpected contexts. For example, we do a show called Night of a Thousand Stevies once a year—a Stevie Nicks tribute held at Irving Plaza with the iconic company Jackie Factory. Stevie Nicks and Butoh—that’s not a pairing people expect, and it certainly raises eyebrows. But it has worked for the past 20 years. It’s in these unlikely juxtapositions that the art form stays relevant and alive. My deep ties to New York’s nightclub and cabaret scene opened doors to collaborations with artists like Machine Dazzle, who is now widely celebrated for his visionary costume work. We’re still collaborating—he’s designing the costumes for my upcoming show MAN WOMAN with Akihito Ichihara.

I’ve always been fascinated by the border between entertainment and art. What’s considered “low art”—a woman dancing in a cabaret or stripping nude—is, for me, still art, even if it’s rarely recognized as such. Then there’s the theater stage, deemed “high art.” I’m interested in everything that exists in between. Site-specific work, clubs, unconventional venues—they create a kind of shock, a fresh encounter between cultures and subcultures. That’s where I believe evolution happens, where the art form truly grows.

Bringing Butoh into these colorful, unconventional spaces blurs the line between entertainment and art, challenging perceptions and allowing the form to evolve in dialogue with subcultures and contemporary communities.

Night of a Thousand Stevies - Photo by Loro E. Seid

I’m curious about how you connect high art and low art, especially through burlesque. How does revealing the body and the sexuality of the body in burlesque relate to your practice of Butoh?

Maybe I can speak on two levels—one is the history of the art form and how it intersected historically, and also how it intersected for me.

At some point in the late 60s Hijikata Tatsumi started working with women only. He had a very influential collaborator, Yoko Ashikawa, and also people like Nakajima, who just passed away. They were very poor and needed money to finance performances, which are expensive. So, they worked in clubs—essentially strip clubs, the 60s version in Japan. The women would work all night long, generating income for the company. Hijikata would collect the money and use it to pay expenses.

That sounds creepy to me—like pimping.

Yes, exactly. I believe the correct term is “proxenet,” but yeah—it’s like pimping. Even some of my male teachers are angry about this looking back, reflecting on the way it was organized. But we have to understand Japanese culture—there’s hierarchy, different norms. Still, they were dancing nude, dancing sexually, and he used the money for the collective.

Butoh at the time was called the “Dirty Avant-Garde” in Japan. It came out of the underground—where sexuality, darkness, the realm of death and sex and everything in between—lived.

Interestingly, Ashikawa was the most talented dancer. Hijikata would lock himself in a room with her, throw images at her, and she would respond. The dances that were born from this improvisation were later codified and taught to other dancers. But this was happening in the body of someone who danced all night in a strip club.

I worked as an exotic dancer and stripper in New York to make money. The proceeds went to me—I had agency. That pimping element was removed. Once I realized the similarities with my Butoh path, I understood the cross-pollination. You work long shifts, eight hours in heels. You have to find more with minimum effort. But it comes from a feminine and sensual source. It’s the same energetic place—the root chakra, the first two chakras, Kundalini energy. Through Butoh, it gets distilled and organized differently, but the source is the same.

I also worked as a ballet dancer. Almost everybody I knew in the 90s who was a dancer was also stripping in New York to make a living. We all had to pay for school or to live. It was a great way to make money—three nights a week, a big chunk of income.

I was not a stripper, but I imagine if I were, I’d put my “dearest” self somewhere else. I wouldn’t want to reveal that self to anyone’s gaze.

For me—and I can’t speak for others—it was always performative. Mask work. Layers. I considered it a role—archetypal. I never felt like it was me on stage. It came from me, but I put filters in place to protect what you describe as your private self. Especially in Butoh, you go so deep—into the unconscious, your body memory, your ancestry. You’re far removed from personality or persona. You go to a deeper place.

So, the woman who taught you in France used stripping as a framework to teach movement?

Yes, to survive as a dancer. I interviewed her for my book. She said one day she looked around at everyone smoking and drinking in the strip club and realized if she stayed, she would die. But when she left, she was able to rescue aspects of movement that could support Butoh—feminine energy, organic movement, the heaviness of the body.

Noguchi Taiso is a release technique where you use minimal effort and the weight of the body. One of my teachers, Yumiko Yoshioka, who worked as a stripper in Europe in the 80s and 90s, teaches movement that’s basically burlesque. Softness, heaviness, letting go—there’s crossover.

You’ve spoken about expanding representation within Butoh, particularly for women and queer artists. How has that focus shaped your work?

Early on, I noticed that in the West, the art form was often framed as sacred, pristine, and dominated by the image of male Japanese bodies. As a feminist, I questioned this narrow lens. Where were the women teachers, the female founders, the diverse practitioners?

But we all know what happens when we leave things to an algorithm and to the internet: patriarchy wins. Male bodies are often seen as more important, more recognized, more talked about. Men end up having better opportunities, making more money, and being ascribed a higher value than women.

I’ve engaged with the art form in New York with a deliberate focus on revisiting that imbalance—creating space for women to be acknowledged within Butoh. And not just Japanese women, but women who don’t necessarily fit the stereotypical image of Butoh: women of color, women from Latin America, trans women.

In response, I founded festivals and curatorial platforms to give visibility to women, artists of color, and queer voices—not only in Japan but globally. I even launched a Queer Butoh festival, because at its heart, Butoh is a queer, subversive art form that resists norms and embraces difference.

Butoh often involves slowness, stillness, and transformation. What happens in your body and mind during those moments of extreme stillness?

It’s important to say that Butoh doesn’t always involve slowness—this is more of a common trope. Some performers, like Sankai Juku and my dance partner Akihito Ichihara, move incredibly fast. That said, my own work often explores slowness and stillness because they’re powerful tools for focus and transformation.

Moving slowly allows me to redirect my attention inward, meticulously scanning and organizing what’s happening inside the body—almost like controlling water through a dam, irrigating the unconscious with precision. This is not just a metaphorical experience; in 2023, I collaborated with neuroscientists at the University of Houston who measured the brainwave activity of myself and four dancers during my piece The Slowest Wave. We discovered that Butoh dancers can reach delta brainwave states—the kind usually associated with deep, dreamless sleep—while still performing complex, controlled movements. It was a breakthrough: achieving a state where, under normal circumstances, humans can’t even move, yet we maintained full motor control.

What’s significant about Butoh is not just the physical movement itself, but the way it engages the nervous system. Motor behavior—the relationship between the brain, the nervous system, the bones, and the muscles—is at the heart of the art form. Butoh dancers learn to navigate this internal landscape with precision, shifting effortlessly between sympathetic (“fight or flight”) and parasympathetic (“rest and digest”) states.

Typically, when the body is aroused—say, running from danger—stress hormones circulate for about 20 minutes before calming down. But Butoh dancers train to move between these states almost instantaneously. This unique ability creates an unpredictable, dynamic presence on stage and allows for a deep, almost meditative state of transformation within.

Ultimately, what the audience witnesses in those still moments is not simply “slowness,” but a heightened internal orchestration of mind, body, and nervous system—a rare state where the unconscious becomes visible through movement.

The Slowest Wave - photos by Michael Blase

Can you describe your process for entering a Butoh state? What rituals, preparations, or internal work lead you there?

For me, the preparation is the 25 years of training and practice I’ve already lived. At this stage, I don’t need any special rituals to enter a Butoh state—the neural pathways and networks that allow me to access it are fully built. It’s like having a bridge already in place; I can cross into that state naturally and almost instantly.

This is very different from the experience of a beginner. When someone is just starting out, they often need very specific conditions: a safe environment, certain music, and usually a guide who can lead them through shifts in attention and states of consciousness. Beginners are learning to navigate between conscious awareness and the deeper, more unconscious layers of the body, while also developing the ability to regulate the nervous system—moving between calm and heightened states at will.

With years of dedicated practice, all that external preparation becomes internalized. The body and mind learn the pathways, and eventually, entering the Butoh state is as natural as breathing.

How do you think Butoh helps us confront mortality in ways other art forms do not?

Butoh naturally alters how we experience time and space. In daily life, we tend to move with purpose: point A to point B, already anticipating the future. Our bodies strive for efficiency. In performance, audiences are accustomed to this rhythm too—a beginning, middle, and end, like in most contemporary dance.

Butoh disrupts that. Instead of moving forward to reach a goal, we drop inward, like lowering a ladder into ourselves. Time becomes suspended. There’s no linear arc, no “next.” We may stay in one moment, repeat an action, or dissolve any sense of a destination. This changes everything—for both the dancer and the audience. Transformation happens not by arriving somewhere, but by fully inhabiting the present.

When you enter this state, you inevitably encounter what we usually avoid: loss, memory, discomfort, the rawness of being alive. There’s no escape into the next task or movement. Butoh asks us not to use movement as an escape mechanism—not to fall into “next, next, next.” Because ultimately, “next” just brings you closer to death. Butoh transcends that impulse. It demands that we become deeply human—whatever that means, whatever arises in the body—without rushing away from it.

It’s not philosophical or abstract; it’s experienced through sensation, through the union of mind, body, energy, and feeling. Something profoundly spiritual happens when all these aspects of ourselves remember one another and come into union. In yoga, the word itself means “union,” and Butoh, in its own way, reaches that same depth of integration.

Many people who join workshops describe it as therapeutic because Butoh doesn’t let you bypass trauma or buried emotions. The body “keeps the score,” and Butoh demands that you move inward and through these hidden layers rather than around them.

In this way, Butoh brushes against mortality differently than most art forms. It suspends the rush toward the inevitable end and instead opens a space where we can fully feel our humanity—sensation, memory, energy, spirit—all in union. It’s a rare experience of presence that feels, to me, like a glimpse of what happens beyond life itself.

You’re working on a duet, MAN WOMAN. Why is the title all caps?

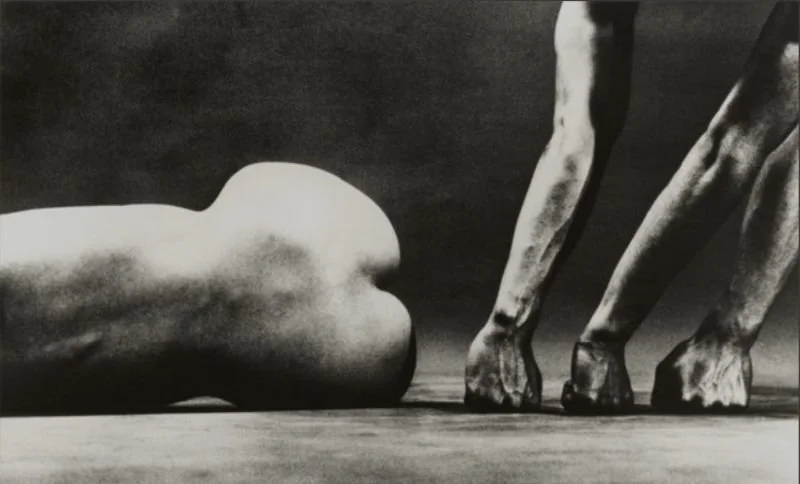

It’s inspired by the book Man and Woman by photographer Eikoh Hosoe. He was a key figure in promoting Hijikata, photographing him alongside famous figures like Mishima. Those sculptural, black-and-white images of gendered relationship inspired us.

When Itchi (Akihito Ichihara) proposed a collaboration, it felt perfect. We’re redefining the legacy—not a man in power and a submissive woman. What does gender mean today? What does it mean to relate? I’m perceived as a woman but feel a strong masculine side. Itchi is androgynous. The all-caps title is a way to say: look at this, pay attention.

Man and Woman #24 (1960) © Estate of Eikoh Hosoe

MAN WOMAN - photos by Michael Blase

When and where is it premiering?

We premiered September 4–5 at Oxford University Performing Arts Center. The New York premiere will be presented in a soon-to-be-announced venue in April 2026.

When we look at all these elements—cross-cultural lineage, unconventional spaces, burlesque, gender, queerness, slowness, and mortality—what is the core of Butoh for you today?

Butoh helps us embrace the bridge phenomenon, connecting across cultures, ancestries, and unconscious legacies that live within the body.

Butoh is not meant to stay frozen in time or preserved in a museum. It evolves when artists engage with their communities and the times they live in. The art form remains relevant when those who practice it redefine it in the making, while being embedded in a community and a specific moment in time—offering classes, workshops, and performances that truly engage with people.

It’s about encounters—between bodies, histories, cultures, and unconscious ancestry. It’s about being present, about suspending time, about inhabiting the moment fully. Through Butoh, the unconscious becomes visible, the body tells stories that words cannot, and transformation happens both internally and in the shared space with the audience.

For me, Butoh is about fluidity—fluidity of gender, identity, cultural lineage, and artistic form. It allows for play between the masculine and feminine, between high art and low art, between structured technique and intuitive improvisation. It embraces the contradictions, the tensions, and the complexity of human experience.

Ultimately, Butoh is a living, breathing, evolving practice. It’s an art form that is continually reborn with each performer, each audience, and each encounter. My work—through teaching, performing, curating, and collaborating—aims to honor that living tradition, while expanding its horizons, making space for those who have historically been marginalized, and ensuring that Butoh remains vibrant, inclusive, and deeply human.

Did you like what you read here? Please support our aim of providing diverse, independent, and in-depth coverage of arts, culture, and activism.

CATHERINE THARIN choreographs, curates, teaches, and writes. She danced in the Erick Hawkins Dance Company in the 1980s and '90s, was the Dance and Performance Curator at 92NY, NYC, for 15 years, and was a senior adjunct professor at Iona College, New Rochelle, NY, for 20 years. She writes dance reviews and articles for The Dance Enthusiast and Side of Culture, reports on dance for WAMC/Northeast Public Radio and writes about performance for the New Pine Plains Herald. She has contributed to the Boston Globe. She programs dance at Stissing Center, Pine Plains, NY and dance movies at the Millerton (NY) Moviehouse. Says Fjord Magazine of her work: 2023 - "The evening was consistently charming, well-crafted and paced." 2025: "Her witty series of dances explores romance and its complications.”