Suffer the Children - MS. RACHEL showcases drawings by Palestinian refugee children in COLORS THAT SURVIVED at Caelum Gallery

Ms. Rachel facetimes with the artists of Colors that Survived. Courtesy Artists Support. Photo: Olivia Wein

Almost anyone with children (or grandchildren, or young nieces and nephews) is intimately familiar with educator and advocate Rachel Anne Accurso, known professionally as Ms. Rachel. For anyone who cares for children, she’s a wholesome lifeline carrying on the legacy of figures like Fred Rogers and Sesame Street.

Horrified by grisly images from the Gaza Strip that we all watched on our social media feeds, Accurso began to use her platform to make simple, impassioned pleas that the massacre of children there end. Inviting a 3-year-old double amputee Palestinian child, Rahaf, onto Accurso’s massively popular YouTube channel served as a flashpoint. It garnered an outpouring of support from those sympathetic to Gaza, and death threats from those who favor Israel’s policies.

Accurso has bravely doubled and tripled down. Her support for young people from Palestine continued with a one-day pop-up art show she curated of drawings by Palestinian refugee children, which opened a week ago at Caelum Gallery in New York. Colors That Survived is a joint venture with Artists Support and the production company behind docudrama The Voice of Hind Rajab. The film blends real phone recordings with dramatization to tell the tragic story of a 5-year-old desperately calling for help while pinned down in the middle of heavy fire. She was brutally killed along with six members of her family, and two paramedics trying to save her. The other partner in the venture, Artists Support, is entering its sixth year of finding charitable uses for the work of artists such as Nan Goldin, Brian Calvin, and Camille Henrot to support humanitarian and environmental causes.

All proceeds of Colors That Survived will go to the young artists and their families, with the sale remaining open online through the end of the month (though it appears to have already sold out). This undeniably generous gesture was widely publicized, but the presentation should be read closely as well. Children deserve to be taken seriously. Not everything needs harsh scrutiny, but everything contains in itself the terms and stakes of what thinking critically about it might mean. These are my thoughts from the exhibition.

All of the available works are print editions and (to my eye) not especially well-produced ones, but not ones the buyer should feel cheated by purchasing for $200, which is the price everything is set at. Producing an edition is a sensible idea if the proceeds will help these kids (more items to sell means more potential sales and more potential money). It still, unfortunately, robs the works of something.

Art school graduates may shiver, cringe, or groan at the mention of Walter Benjamin’s famous essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” and it’s easy to overstate the intrinsic aura of a unique object as superior to its copy, but the simple fact of a singular piece of paper that a child put time and creativity into is poignant by itself. That’s before even thinking about everything these kids have lived through. Those love hours aren’t quite present in these reproductions.

Installation view, Colors That Survived. Courtesy Artists Support. Photo: Olivia Wein

The exhibition doesn’t let you forget the horrors, either. Printed statements next to the works on the wall, written by the artists themselves, about their struggles, are hard to read without tearing up a little. This can feel superfluous. Everyone who came to the show knows why they were there. This framing sometimes doesn’t allow the work’s own wild creativity to speak for itself—except for the bracing moments when the words are a heartbreaking foil to what we see.

A confident drawing by Ahmed has an immediately affecting clarity, lightness, and directness. It’s a presumable self-portrait showing a heavy load on his back shaped like a house. Ahmed uses the statement hung by his work to unpack the metaphor, talking about quickly filling a bag with as much of his life as could fit, not knowing he would never see his room again. The new blue soccer shoes under his bed are gone forever. It’s instantly as iconic an image as Handala, the grubby cartoon refugee child with patchy clothes standing with his hands behind his back, who has been a symbol of Palestinian oppression and resilience since 1969.

Ahmed, House On His Back, 2025. Digital Print, 11 x 14 in. (28 x 36 cm). Edition of 20, numbered. Printed by Press Friends, Los Angeles. Published by Artists Support. Courtesy the artist.

The words that cut deepest come from one of its youngest artists. Maha draws a guileless sunshine-kissed family portrait in They Are My Family, its title written in exuberant letters that squeeze together excitedly over a smiling family unit. Smoke rises from the chimney of a house, and fruit ripens on a tree beside it. “I wait for the war to end,” Maha says in her statement on the wall, “so I can go to the graves of my mom, dad, brothers, and sister to tell them to wake up, the war is over.” This picture could pass for any child’s fridge drawing if you didn’t know it was a memorial.

Maha, They Are My Family, 2025. Digital Print, 11 x 14 in. (28 x 36 cm). Edition of 20, numbered. Printed by Press Friends, Los Angeles. Published by Artists Support. Courtesy the artist.

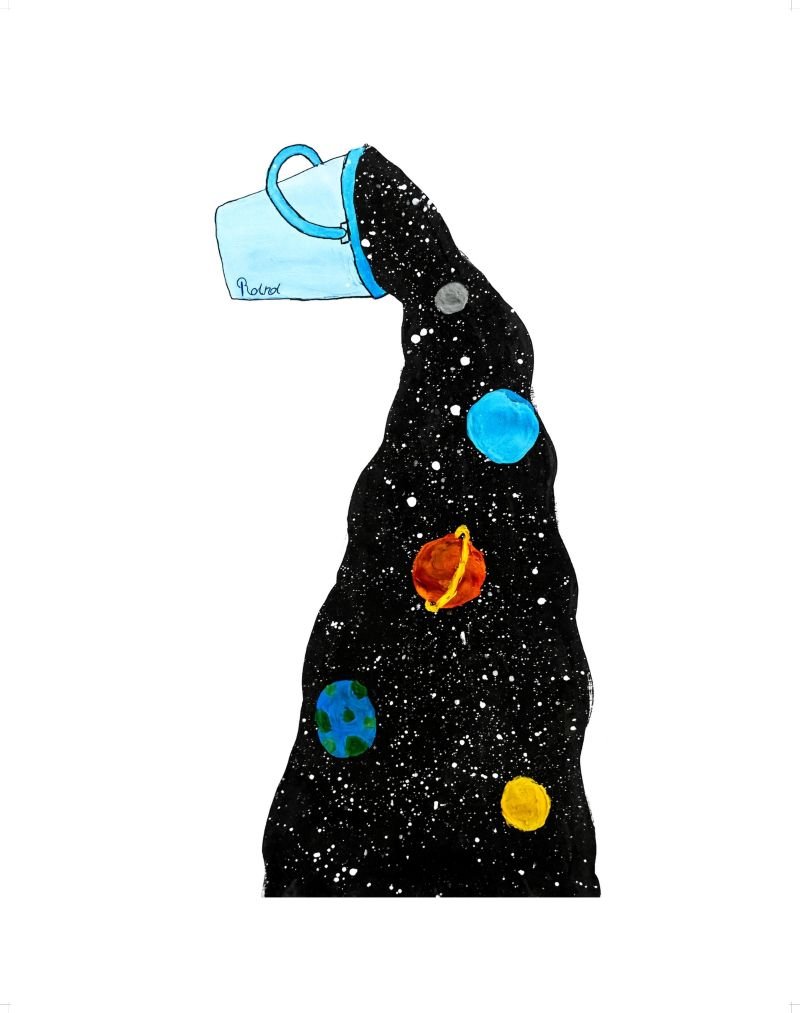

Ahmed and Maha stand out for the way their words and their artwork complement each other, but there are pleasures and depths in every picture on view: a rainstorm of patient, evenly spaced droplets falls on Hala’s It’s Raining. Yamen’s vivid Picasso Tree looks like a gorgeous batik work on fabric. Shahed, Luna, and Sarah play with the four colors of the Palestinian flag and the euphemistic device of the watermelon. The fruit became a popular symbol of support for Palestine between 1980 and 1993, when red, black, white, and green—all naturally found in a juicy slice of it—were forbidden to appear together by the Israeli government. Yara and Rafah’s Manga-inflected work shows great promise for careers in illustration, while Anne’s Peace Dove and Mohammed’s Yellow Doves are sanguine psychedelic visions like something out of Peter Max. Rama’s Walking to School adds a beautiful comic verve to an aspirational, untroubled commute. Finally, Rana’s Pouring the Universe is the most abstract and imaginative, showing a simple bucket able to contain and release a universe of stars and planets.

Rana, Pouring the Universe, 2025. Digital Print, 11 x 14 in. (28 x 36 cm). Edition of 20, numbered. Printed by Press Friends, Los Angeles. Published by Artists Support. Courtesy the artist.

Children’s art sits in an interesting place within Modern and Contemporary art. Arguably, Cubism owes it a debt. Artist Brian Belott’s long-standing engagement with children’s art and the thinking of Rhoda Kellogg, a theorist of children’s education and creativity, asks interesting questions about artistic ingenuity. Another artist, a friend of mine, Craig Hein, is a teacher himself who periodically mounts similar exhibitions of his students’ work in galleries like Caelum. They’re always beautiful. They show a great love and respect for the work and for the kids. I learned to see children’s art through those shows. It can be a challenge to bring your adult self to appreciate untrained smears of crayon, paint, marker, and pen, but it’s a rewarding one, and an important one.

The best argument for discussing this presentation with clear eyes comes not only from a love for the raw mark-making a child is born mastering, but from past epochal atrocities. Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, a student of the famous Bauhaus, secretly taught art lessons to over 600 children in a ghetto in Terezin. She was careful to have each of them sign their names to the works. Before transfer to Auschwitz-Birkenau, where she would be killed, Dicker-Brandeis smuggled out 4,500 of the drawings in two suitcases, which eventually came to the collection of the Jewish Museum in Prague. Only about 100 of the drawings’ young authors survived the Holocaust, but all of their names persist as a reproach to anyone who would do such violence at such a scale to children. Children’s art education has a heavy bearing on history, and educators deserve all of our support for what they do for our children and grandchildren. As we survey a present-day conflict that continues unabated by ceasefire, in which at least 64,000 children have been killed, “never again” must truly mean “Never again for anyone.” Especially the littlest of us.

Joshua Caleb Weibley is a writer based in Brooklyn, NY. He also acts as executor of the estate of Joshua Caleb Weibley, which has staged exhibitions at various venues in America, including Game Transfer Phenomena at CHART gallery early in 2025.

Did you like what you read here? Please support our aim of providing diverse, independent, and in-depth coverage of arts, culture, and activism.