ADRIANA CIOCCI

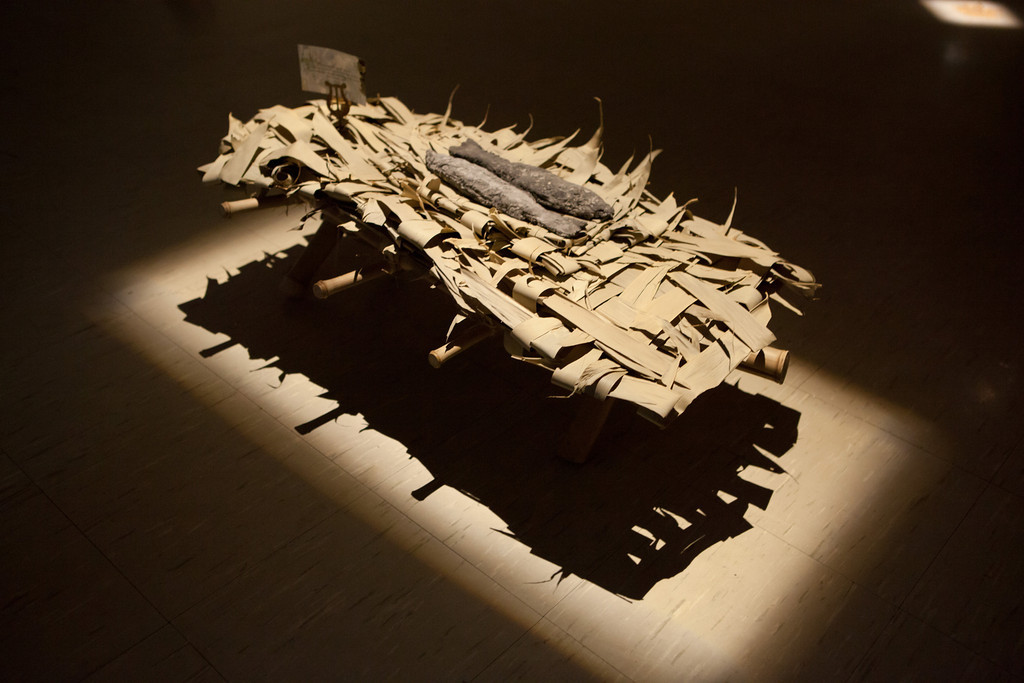

“The Blood That Runs Through Your Veins Is The Same That Runs Through Mine”

Sculptor Adriana Ciocci burns, melts, and breaks various discarded objects into new forms. In this interview, she talks about the importance of her relationship to the materials she uses for her art, along with her creative processes and inspirations.

Interview by Megan Farrell

All of the works on your website have a title card printed on pieces of a map. What does this symbolize and how does this detail impact the work they introduce?

The pieces on my website are from my graduate thesis show, Breath Beyond Breaking. I chose to use maps in order to make the work accessible for people from different parts of the world and to speak to diverse experiences, despite the fact that my work is usually based on my own personal experience. Since materials I use are integral to the meaning of my work, they must be expressed and understood in context, which is why I didn’t use the traditional method of listing the titles and materials.

In your artist’s statement you say that you are inspired by broken or discarded objects. Where do you find the materials for your work? Do you have an idea of what you want to create either in a physical sense or the metaphoric before locating the materials, or does the process of creation start after the materials are found and taken apart?

My inspiration is somewhat experiential. It can come from finding an object, reading a book, or hearing a song. I keep an ongoing list of titles, materials, and forms that I’m interested in. As I investigate the possibilities of each separately, my research overlaps. These overlaps are what I use to build a narrative and meaning. I collect materials from places I’ve lived or visited, nature, grocery stores, eBay, and Craigslist. The title for my piece, “The Blood That Runs Through Your Veins Is The Blood That Runs Through Mine,” came from a letter written by my father to my uncle. When I came across it, I was living in Italy during the period between undergrad and grad school. I was teaching myself Italian through reading letters and books of poetry, taking sewing classes, and watching the old movies playing on Rai Uno every Sunday. At the beginning, the idea of using the form of the violin was unconnected to the title. I wanted to create an instrument that would be a complicated mold-making project.

On some level, it was nostalgic because I played the violin when I was younger. I was also thinking of a book of poetry called Gardens of the World, by Radcliffe Squires. There is an excerpt that reads, ”...all music is a lost self, and the lost self returns to you only when your grief for him makes you kind.” I loved the idea of grief leading to humility and kindness as much as I loved seeing a visual symbol of music as a representation of grief. The materials came from a walk up the hill from my bus stop to my apartment. I had made the walk several times, but on one particular evening I noticed some cicada exoskeletons stuck in tree sap. At that moment, all the parts fell into place and I knew what the piece would be. The surprise was how it would behave in the gallery, under the lights slowly buckling and sagging and ultimately melting from the heat. Its slow progressive decline made it more tragic and alive.

“La Storia Dell’Uomo e Legata al Mare”

“La Storia Dell’Uomo e Legata al Mare” is an interesting work because you physically put yourself into it. The piece is composed of a violin bow suspended from the air with your own hair coiled down from It. What drove your desire to use your own physicality in it? This also is cited as perhaps not fully finished on the title card reading “2010-present.” Does this mean that you are still adding to the project?

The title for this piece came first. It is from a children’s book illustration depicting a man on a boat with a net with the caption, “La storia dell’uomo e legata al mare,” meaning, the history of man is tied to the sea. I had found the book in my family’s home in Italy, and I thought it was so poetic and poignant. I’ve always been attracted to bodies of water even though I’ve never lived near one. I kept the clipping on my studio wall when I was in grad school. I had a critique in the first half of my first semester and a criticism was brought up, that my desire to use only personal materials, which were finite, made the viewer less likely to build a relationship with the works, and limited my creative scope. After returning to my studio, I was thinking about this criticism, when I noticed an image of a mummy, found in the mountains of Peru, from research for my Latin American art history class. She was frozen with even her intricate small braids intact. I noticed this and thought about using a personal infinite material source: my own shedding hair. So, I started braiding, then building braid upon braid. As the length grew I considered the shape it could take. Noticing the photo of the man with the net and the caption, the work made sense. I loved the idea of putting myself into that history of the fisherman and the sea, and the implications of the connectedness of all things; all fisherman, bodies of water, peoples, and histories, both personal and collective. I am still working on this piece periodically. It’s outgrown the violin bow and now hangs in my studio from hooks. My hope is that it will grow larger and grey into my old age.

Many of the works on your site use musical instruments or parts of the instruments to create a larger sentiment or statement. What is it about these discarded instruments that is so appealing to you?

It started with the quote from Gardens of the World. I put up a Craigslist ad and sourced instrument parts from some interesting people. The owner of the violin said it was his first, which he had used when he was younger. It still had the tapes he had placed as reminders of the chords. The brass parts and spit pads came from different sources, one of which was a man who was a career musician and musical instrument restorer. His house was full of birds, which seemed fitting. The connections I made with these people made the process more exciting. I liked the idea of being tied to the musicians that played the instruments, and that I was figuratively breathing new life into them by turning them into something new and whole.

I filled my studio with the hoarded musical instrument parts and thought about what I could do. Slowly, the spit pads and brass parts became candelabra and sconces, and the violin bow, the hanging apparatus for the net. The music holders became a way of linking the materials to the artwork, as well as making the show more cohesive. I loved the element of implied sound. As you walked in the room it was silent, but when you looked at the piece with the violin and cicadas, or the brass instruments, you could imagine the sounds they would make. To me, it felt more meaningful because it was engaging the viewer differently; more like reading a novel, where you build your idea of characters and places based on your own understanding. The mental work of the viewer mining their own experience creates more of a connection, taking longer to digest, and making the work more relatable to personal experiences.

“Breaking in the Field”

“Because It Brings Me Back To You”

“Fallen Figs”

Works like “Breaking the Field” and “Because It Brings Me Back You” are displayed on the floor rather than a podium or another elevated surface. Others like “Fallen Figs” are showed both above the viewer’s head as well as below them. How do you feel that having the work lower than the viewer’s eye level change the perspective on each piece?

I wanted the viewer to engage with the work differently than the standard gallery or museum method of a meeting at eye level. I did this in my thesis show by bringing the viewer to the work’s level instead. By bringing the viewer down to the floor or directing their focus above their heads, my hope was that it would create more of an intimate space and also would be reminiscent of experiences in the real world. My goal was for the work to remind of real things, like horse tack hanging in a barn, pots and pans in kitchens, meat hanging from hooks in butcher shops windows, fallen fruit in an orchard, or shells along a beach.

“Because It Brings Me Back To You” is a work that is time sensitive to view, as part of its component is a mold of shoes made with frozen wine that melts the longer it sits under showcase lights. What is it like creating a piece that you can watch fade away? As each element contributing to the overall work once belonged to your father, would you consider this a tribute to him?

Yes, it was a tribute to my father. He passed a few months before the piece was finished. I had already put in the research for making and freezing the lilac wine and chosen the form of the shoes. The title came from the song “Lilac Wine” which I loved because it was so sad. The narrator is longing for someone, making the lilac wine to bring them back, and then progressively becoming inebriated and hallucinating their return. I was introduced to the song by an ex, and I originally thought the piece would be about him. When I considered the form, shoes where my choice because they could stand in for the absence of him in a tangible and relatable way. When my dad passed, it made sense to use him as the subject since his loss was so much more profound. As I sorted through my father’s clothes, deciding what to keep, I took a pair of his shoes and shirt I remembered him wearing. I realized I could use an outfit of his to make an element of the piece. I made a mold of the shoes, froze the wine in an on-campus creamery deep freezer, and wove stripes of his pants, undershirt, and shirt. I wove them so tightly, the rag rug became a basket, which physically and symbolically showed my desire to hold onto to a piece of him.

It was so strange to see the piece melt. I was reliving his passing, but more cathartically since it was somewhat on my terms, even though I couldn’t control the rate of melting. I could only watch and have it documented. Letting go made the process more meaningful since I couldn’t predict how the work would behave, nor can I predict how the viewer will see it. This is mostly true of all artwork, but artwork made knowing it will fade gives up much more control. For that reason, it is more enriched with the possibility of interpretation. I want the viewer to see themselves in it; to feel that the process of deterioration is in some way reaching them and their own experiences of loss.

Light and lighting fixtures are an integral part of the display of your creations and greatly alter the way that the art is experienced by the viewer. When you put together your sculptures, are you thinking of lighting in any specific way? Do you feel that the shadows of the sculptures also have an impact on the story told or the feelings they evoke from the viewer?

I don’t think a work is complete until it’s installed and lit, so it is the final part of the process, but not something I design while I make the work. I make with the expectation that the environment around it will conform to it or disappear. Once it’s in a space where it will be viewed, I want the work to be the focus. Anything I can do to control the lighting is done to highlight the work itself. I do play with shadow and shapes of lighting, but not until the work is in its intended space.

You label your works as being “full of tension frustration and doubt.” What is it about these feelings that make them to appealing to you as an artist?

The appeal comes from how I see my materials and the resulting completed artworks as stand-ins for relationships. Even if I’m not basing an artwork on a specific person or experience, I’m still building a relationship with the material itself, finding the best attributes, and testing boundaries. Literally bringing materials beyond their breaking point gives me a sense of what the materials can do, and creating this stress reminds me of close relationships to loved ones. Most relationships are complicated, frustrating, layered, and full of dualities that lead to self-reflection and personal growth. These experiences are potentially enriching but can also cause the deepest emotional wounds. Building with materials makes me think of this duality; the beauty in the pleasure and the pain of relationships, that both inform who you are and constantly challenge you to evolve. My sculptures are highly imperfect. They have been bent, burned, broken and melted into a shape that will often unravel under the right temperature or over time. I see them as monuments to change and the beauty of imperfection, which is the biggest part of being human.

“The Echo of Great Spaces Traveled”

“The Echo of Great Spaces Traversed” includes a burned copy of Swann’s Way by Proust turned to ash and reformed to resemble fish. What in this book resonated with you enough over other stories to make it a centerpiece in the work? Do you find that books regularly inspire your art or give ideas into new projects?

Yes, I’m often inspired by books. For this particular piece I chose Swann’s Way. It’s the best piece of writing to describe what I’m trying to achieve visually. I would say that I’m trying to capture the fleeting essence of loss and nostalgia. It’s particularly relevant because tastes and smells can transport you back to a memory so vivid it feels like you’re actually reliving it. The distance between the memory and the reality are both heartwarming and heartbreaking. The words were such a powerful inspiration that I felt I needed them to be a physical part of it. So, I burned them, mixed them with bookbinding glue, laid them in a mold of a branzino, backed them with kelp, stuffed them with salt and sewed them into wholeness. I loved that the symbol of the fish because it could be from South America as easily as Asia or Africa. It could also represent the fisherman or the consumer.

The form of the fish was also partially based on a memory my dad recounted to me of an experience he had in Vietnam. I remember him telling me about going to a shack on a beach which had become a restaurant serving freshly caught fish, cooked over an open fire. It was one of the simplest and most delicious meals of his life. The story made me feel a longing and a sort of transferred nostalgia for travel I wanted to experience. I think reading is often similar. We read to escape and daydream of experiences we wish to have. I like the idea that my work can be seen as a narrative. I think being inspired by writing will always be part of how I create.

“Iron Casting of a Lion’s Head”

Your more recent works all revolve around more solitary objects, like the “Iron Casting of a Lion’s Head,” which will become the centerpiece of the final project. How do projects like these change the perspective of the audience, having a singular focus rather than a piece in motion, like “The Blood That Runs Through Your Veins Is The Same Blood That Runs Through Mine”?

The recent pieces are unfinished but I can already tell they are moving in a new direction. Since graduate school, my studio practice has evolved to accommodate my changing schedule and lack of access to work space. I collected materials as a way of continuing my studio practice. Eventually, this evolved into forms that were more singular and solid. They are just starts to ideas; tangible configurations to correspond to my lists of materials and forms. I’d like to see the lion heads and other in-progress sculptures completed. I’m still in the process of imagining what that might be. The right materials haven’t presented themselves yet. I believe I’ll introduce more transient elements into the display in the future. Hopefully, the audience will respond to the contrast between the solid abutted against the ephemeral, seeing in it their own experiences of steadfastness and impermanence flowing into one another.

“Dice” - Materials: fired clay dug from a riverbed in Peru, lost wax silver cast, and kiln cast glass

“For Not Forgetting”

There is a work currently in progress depicting a set of dice, alluding to chance and divination as part of the greater theme. These dice are made from clay found in the riverbeds of Peru: were you personally in Peru to gather the clay, or was it sent to you like the feathers in “For Not Forgetting”? What is the connection between the country of Peru and the theme of chance that makes these two ideas compatible within the piece?

Peru is tied to chance in that I took a series of calculated risks which led me there last year. I grew tired of daydreaming of places I might never see and gave notice to my employer. When deciding what to do next I found residencies abroad that focused on topics I wanted to explore. In Peru, I participated in two consecutive residencies over six weeks, learning from Maria, an indigenous textile artisan. She taught me natural dyeing and backstrap loom weaving. I also went on outings, one of which took me to a riverbed, where I collected clay. I didn’t know it would become the dice until I started to experiment with a mold I brought with me, which I made over a year before. I liked the idea of referencing a game that was ancient and that the meaning of a game can change depending on the perspective of each participant. After some research, I learned that one of the first purposes of dice was divination. My work has a lot to do with chance and the path that is created out of the effect of each decision on the next. It felt right to make an artwork that incorporated into it a larger history of randomness.

View more of Adriana’s work on her site

Breath Beyond Breaking thesis show photographs by Cody Goddard

Main page photograph by Shoko Tsuji

You might also like our interviews with these artists:

Megan Farrell is a twenty-two year old writer and filmmaker who lives in New Jersey. She has recently graduated from the University of Alabama with a dual degree in Telecommunication/Film and Economics. In her spare time, Megan enjoys amateur photography and playing tennis.