KEN WEATHERSBY

“292”

Montclair, New Jersey-based artist Ken Weathersby currently has a solo show at MINUS SPACE in Brooklyn (through January 30, 2021). About the show, MINUS SPACE writes: “For two decades, Ken Weathersby has produced deeply-inquisitive abstract paintings, reliefs, and sculpture that play with and against established formal conventions and expectations. For his new Dream Paintings, he works within a structured set of aesthetic variables, including size, orientation, materials, and strategy, which according to the artist, parallels our own repetitive sleep / dream / wake circadian rhythms. Each painting in the series combines an abstract or decorative pattern with an inset window publishing a single handwritten narrative in ink on paper recounting a dream the artist recalled having. The dream texts are generally elusive, neither significant or banal, but ambiguous and possibly inert, leaving one to wonder what the dreams of the artist, or our own for that matter, might signify, if anything.”

Interview by Isabel Hou

You currently have a solo show at MINUS SPACE in Brooklyn displaying the Dream Paintings collection. Two strong components of this collection are recurrence and geometry; the lattices in “292” and “302,” for instance, and the patterns in “310” and “298.” The transcendental nature of dreams placed against such a grounded background can be viewed as a stark juxtaposition. What do you hope to convey through this contrast — or rather, are the backgrounds and stories complementary to each other?

Yes, it is about those thing encountering each other, though I don’t know if dreams are transcendental. I am not interested in dreams as something prophetic or profound; they might just as likely be banal or meaningless. The interesting thing is that there is something genuinely uncontrolled about them. We are bombarded by narratives and statements all the time, but unlike all of that, dreams cannot be deliberate manipulations. They are not the product of a marketing pitch or an ideological strategy. They can be infected by those things but they don’t answer to them. They are beyond the grasp of control. So I am placing them within an object, an abstract painting, and I’m interested in these two kinds of things conjoined. The painted part and the text each have distinct properties but no predetermined meaning, so the painting, which is the meeting of those two elements, and its meanings are the products of that interaction.

“302”

“302” (detail)

“310”

“310” (detail)

“298”

“298” (detail)

You have mentioned visions and dreams as occasional kindling for your inspiration (MS Modern, 2015, and Aferro Studios interview, 2020). How do you flesh out those images and ideas and put them to work?

I would put those two things (visions and dreams) in different categories. There is a kind of beginning of things which I may have referred to as a vision (did I use that word?). If so, what I meant is when an idea spontaneously comes, when an image just appears in your mind. I think this happens to everyone, little thoughts or images or imaginings are in your head for a moment between paying attention to other things, or when about to fall asleep, or other transitional states. I am very committed to paying attention to those moments. Often it’s very subtle and it’s easy not to notice this, and images are soon forgotten. I try to notice and make a sketch or at least notes. Bodies of work I am involved in now started in this way.

The process in the dream paintings is very specific and a little different. With those I am using content that arrived while I was sleeping, in dreams. Again, everyone dreams at night, but normally we don’t remember, or maybe we do for a moment waking up but then we ignore them and they are gone and forgotten. For five or six years I had making a practice of paying attention, writing them down as often as I could, so I thought I could insert a different kind of content into some abstract paintings — instead of photos which I had used before in that way, it would be a written text. It’s even more opposed to the abstract painting than the photographs because it’s not even a visual image. It works differently, has a different syntax. I already had the dream texts so it was ready-made, free content. The dream texts belong to me, I am the author, even though I did not compose them or control what they said. So I began a series of paintings where in each case an abstract composition or pattern contains a dream text (just as the night’s sleep contains the dreams.)

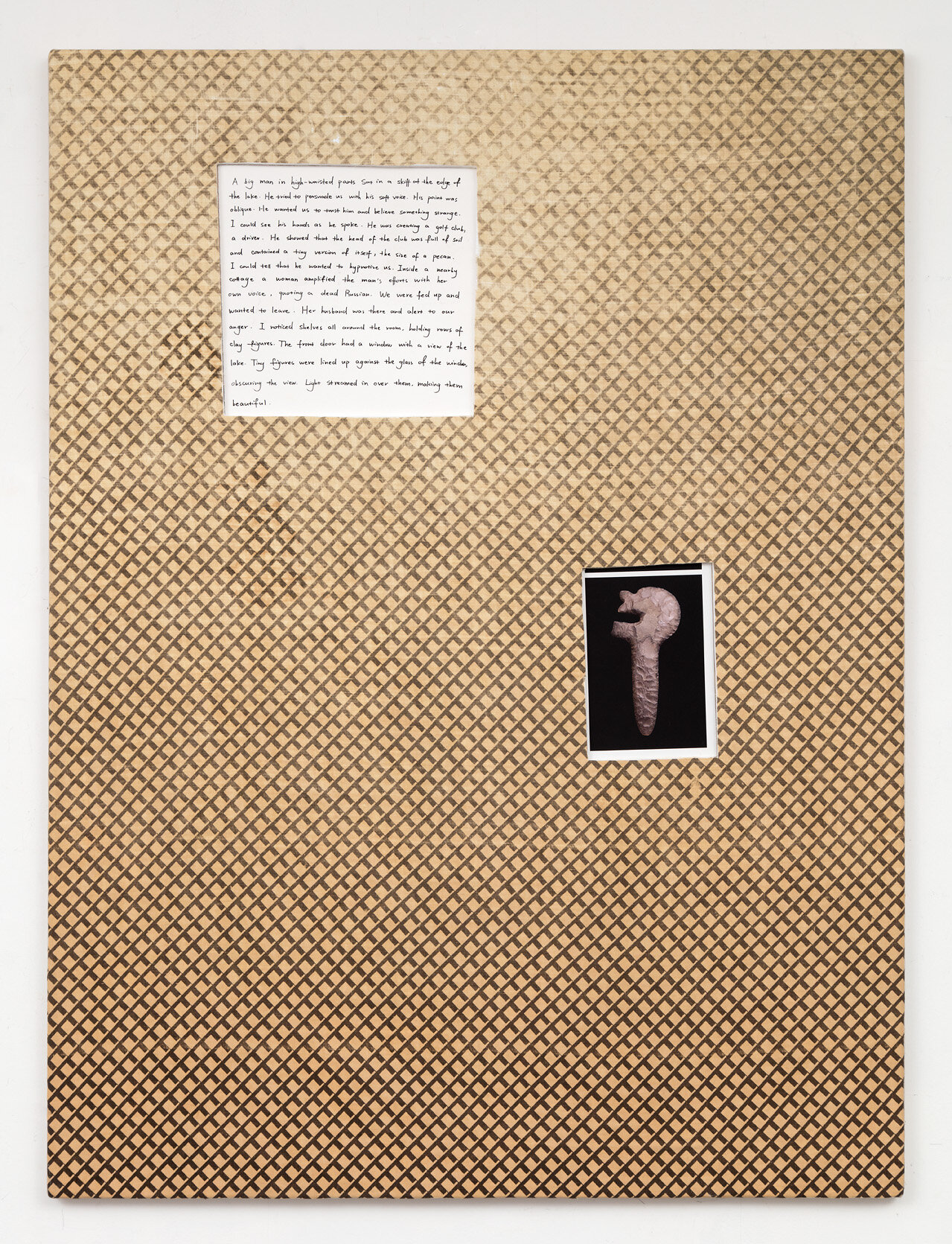

“299” has caught my eye time and time again. Perhaps it is the subtle curve disrupting the uniformity of the lattice print, or the unique photograph collaged into the piece. Or maybe it is the dream itself, which ends with: “Tiny figures were lined up against the glass of the window, obscuring the view...Light streamed in over them, making them beautiful.” How do the components of this work — the painting, the collage, the story itself — reflect your dream?

Any answer to that, to how the painted part and the text and the embedded image relate to each other, and what emerges from experiencing that relationship is for the viewer to see, and may be different from person to person. There are a few things I can say, though. In all of the other works in this group, the abstract, patterned part of the painting is hand-painted. This one is different. The surface is actually covered with an old and worn bed sheet. The pattern printed on the sheet is one that interested me because its small square grid in muted browns looked so much like some of my earlier wood-lattice pieces. The scale of the grid was such an exact match to the wood that I actually used other parts of the sheet in one of those pieces, letting the fabric exist ambiguously next to the actual wooden layers it resembled. In dream painting “299,” the sheet itself is attached to the surface with a layer of medium, in place of a painted composition. The slight curve you see is a little aberration in the way the fabric stretches across the plane. I was excited in this painting by the way there is a subtle glowing aura around the inset text area. That glow is a product of the aged and worn nature of the sheet. It is simply so thin in that area that the white underpainting shines through and creates a painterly chiaroscuro effect. I appreciated how this came about through the given, physical properties of the object, the sheet, rather than through subtle brushwork or color-mixing. And it’s not lost on me that this painting with a dream in it is made of a bed sheet that I’ve actually slept and dreamed under, though I didn’t think of it that way until after the painting was made.

“299”

“299” (detail)

You play with perspective in “297,” placing the story angled toward a circle emanating rays. Behind it, a gentle transition of warm hues. This dream is particularly transient. Some lines include: “...someone somewhere screamed...It was strange: a single high unwavering note...When I looked again we stood on a subway platform...A woman lay curled up in a pile of blankets and coats.” Talk a bit about the meaning behind this piece, particularly that behind the physical placement of the dream.

The image part of this painting came from something I saw in a movie theater. There was advertising before the start of a film, giant sunburst across the screen, as a background behind whatever the product was. The effect was simple and stark. It didn’t make me want to buy the candy or whatever, but it struck me as violently (if unintentionally) sublime. I remembered the image and it became paired with this dream text. I thought about the absurdity of the whatever dumb thing was being advertised flying out of a cosmic sunburst, and how for a dream painting, the implied (but uncertain) significance of something emerging from the center of such an image would be interesting.

“297”

“297” (detail)

You have observed that people find aspects of their past in your work, particularly in your pieces involving wooden lattices: “They [the wooden lattices] especially seem to inspire this response...they seem to touch on or be reminiscent of lots of different things, while still being rather particular.” (MS Modern, 2015) Do you think that this was intentional on your part, perhaps a reflection of your own inspiration found within the structures?

The short answer is no, it was definitely not intentional for me to raise people’s memories of other object-making traditions, but I was not sorry to see such associations emerge. The artist and writer Tom McGlynn once looked at some of those pieces and responded that he thought they were something to do with primitivism. For reviewer Mostafa Hedaya, they raised a comparison with mashrabiya, a kind of projecting window screen of the Islamic world, which I also was not emulating (but which is obviously very sophisticated and not at all “primitive”.) My route, in the case of the wooden lattices, was through elaborating the wooden structure that exists behind and supports the canvas in paintings. I was involved with the idea that a painting is a physical thing, not just an image; that its parts could escape their normal order of priority. I let the wooden, structural part grow beyond its usual role in the simplest way, by building up layers. I think the evocation of other traditions, whether it be the things I mentioned before, or Japanese shoji screens or other things, came through my intersecting with basic logics of structure. I like those associations but I wasn’t seeking them.

Recently, your pieces have included portraits — some photographed, others collaged. Visually, this is a shift away from your work involving wood. To what do you attribute this change?

The works you mention with photographs are the ones I call Disjoined Hand. The link with the works using wood is that both are really involved with the object-nature of the art work. The photos of people are physically inset into the surface of the painting, within a recessed, cutout area, to preserve a sense of distinctness of different things put together, but with some unresolved tension about what their relationship is. There is a common thread; the wood pieces also all contained or surrounded some part that was not wood, usually a printed or painted image, so the aspect of collage was already there.

Those photo pieces, the Disjoined Hand works, followed a group of work that I called Library Hand, in which the inset image was a reproduction of an ancient figurative sculpture, cut from an art history book (I collected many that were being discarded from a library). So in those I was specifically interested in having this mediated thing from the past, a printed reproduction of a photo of a sculpted human image bumping up against the actual, present physicality of the abstract painting into which it was embedded. It’s about things different in kind and also from different times being put together.

The Disjoined Hand paintings with photos of real people came after. With those I wanted the same conjoining of an image of a human with an abstract painting, but without raising the topic of ancient sculpture. So I photographed people that I knew, and those images became the inset photos. I don’t think of them as portraits, since my interest was in what happened between the image and the painting, that relationship, rather than the portrayal of an individual. But of course they can be read in different ways.

The titles of your pieces, you have said, are numbers for practical reasons — the numbers maintain chronological order while distinguishing them from one another. You have also stated that you tend to avoid “more evocative titles” so as to allow open-ended viewer interpretations. (Not What It Is, 2016) However, you categorize your work with [series] titles like Disjoined Hand, So-Called Paintings, and The Path of the Needle. Can you expand on those titles?

For a long time my work proceeded from piece to piece, painting to painting, one at a time. Whatever idea I was working on was the thing, and each piece in sequence was another aspect of that idea. Sometimes I moved on eventually to another starting idea and that would be another body of work. But in the last few years, I find that I have multiple strands, multiple bodies of work happening at the same time. I didn’t plan that and at first it worried me, but I’m very committed to following what feels most compelling in the studio, so I am going on with them. Having those different titles is a way of organizing and identifying the different bodies of work. The Path of the Needle sounds like it might be about heroin addiction, but it’s not. It was taken from a Walter Benjamin quote where he talks about the complicated structure that develops on the back side of a piece of needle-work, which is integral to the structure of the front but not meant to be seen. The works in that category are paintings that deal with the back and underlying support of the painting, often reversing parts of the canvas to show what’s underneath. So-Called Paintings are works that nominally have the conventional ingredients of paintings, but where I don’t use them in the “right” way.

In an April 2020 interview with Aferro Studios, you lamented the negative effect that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on your work. With so much time having passed, how has your perspective shifted, if at all?

The pandemic has had a huge devastating and deadly impact for many, but I don’t recall lamenting its effect on my work. Maybe I mentioned that it led to the postponement of some exhibitions, but it would seem stupid to complain about that in the face of real suffering. In terms of my work during this time, I have found that I have been, maybe strangely, very productive. Unavoidable limits, like not being able to work in my large studio space in Newark for long periods during lockdown, have led me to embrace working within changing circumstances. It has prescribed that I work at different scales and with different tools than I might have otherwise. It has created intense feelings. Indirectly, it seems to have led me to new images and ideas. This, combined with the shutdown of so many things creates an unavoidable subject matter shared by many people at the same time. When the work is driven by circumstances in a concrete way, I think it can connect to reality in a special way. The pandemic is bad in so many ways but it hasn’t been bad for my relationship to my art-making practice.

View more of Ken’s work on his site and Instagram

Dream Paintings is on display at MINUS SPACE through January 30, 2021

You might also like our interviews with these artists:

Isabel Hou is a student and artist interested in writing, advocacy, and law. She is based out of Pennsylvania and is currently living in Colorado.