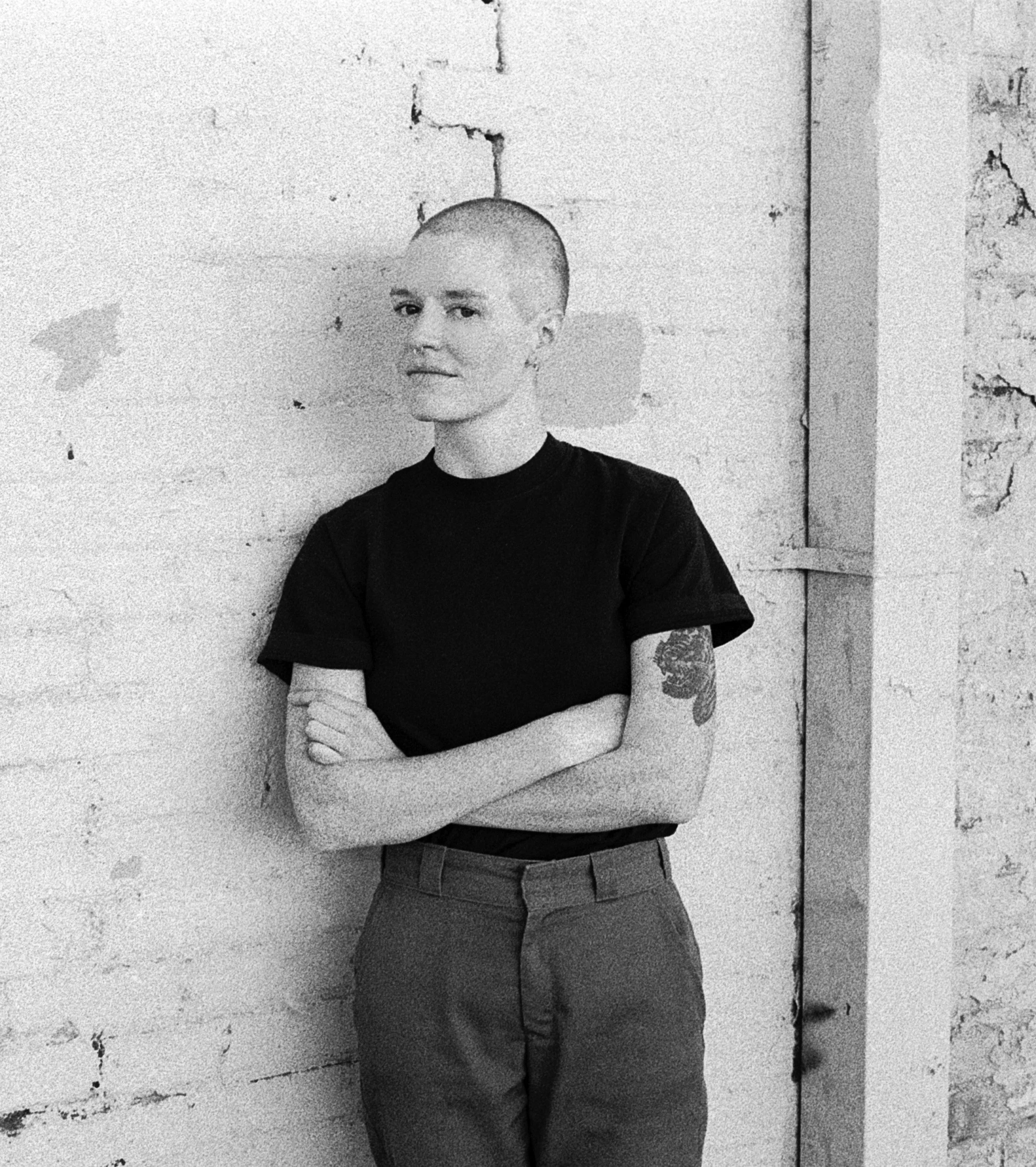

ALINA GRASMANN'S Grand Buffet

German artist Alina Grasmann currently has a solo exhibition called The Grand Buffet at Fridman Gallery’s Beacon, NY location (on display through July 24).

From the gallery’s site: “The Grand Buffet is an homage to, and a celebration of, Haus Schminke, an iconic example of organic architecture in Saxony, Germany designed by Hans Scharoun. A prime example of classical modernism, Haus Schminke has become another site of play and inspiration for Grasmann. As before, she works with the interiors and exteriors of real spaces, adding layers of mythologies, riddles, and personal touches.”

Interview by Tyler Nesler

You paint series that are rooted in specific places, as seen in your Sculpting in Time exhibition for Fridman Gallery in 2020, which focused on the Arizona experimental community of Arcosanti, and The Montauk Project, which depicted locations in Montauk, NY, with a history of mysterious conspiracies. With The Grand Buffet, you've focused on the Haus Schminke, a primary work by the architect Hans Scharoun and a revolutionary work of modernism. What key elements to this house attracted you to it as a subject?

Having focused on places in the US in all of my previous series, I wanted to paint one about a place in Germany for quite some time, but I had the feeling that I needed to have a bit of a distance and that I would like to show this series somewhere else, not in Germany.

In my work, I always try to negotiate proximity and distance in some way. Bringing a house from Saxony to the Hudson Valley gave me enough distance from the place of origin.

Also, the Fridman Gallery space in Beacon is smaller than the gallery in Manhattan, and Beacon is much smaller and more intimate than New York City, which led me to get even closer to my subject. I had always focused on entire towns like Arcosanti or Montauk. For the exhibition in Beacon, I wanted to focus on a single house, the Schminke House, and get close and personal with it.

The house was designed and built by Hans Scharoun in the early 1930s for a family of entrepreneurs. The architecture of the house can be classified as “classical modernism” and is reminiscent of other private houses of that era designed by world-renowned architects such as Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe. But for me, this house also has similarities with Arcosanti – round forms and a porthole-like window at the entrance.

That's one of the reasons the house was nicknamed “The Noodle Steamer” – an entire cosmos of thoughts, feelings and stories is contained in this “ship of life” anchored behind a once-famous pasta factory. Bold dreams of the future and social utopias are embedded here alongside personal and historical tragedies. But what I particularly like is the variety of possible perspectives from which one can approach the phenomenon that is “Haus Schminke”. Viewers of my paintings can bring their own questions and thoughts into the pictures, and perhaps even find places within them where they can become the protagonists.

On the other hand, it is far from my intention to represent Haus Schminke simply as an architectural masterpiece or to illustrate the history of the house and its inhabitants. In general, I don’t want my paintings to tell stories. Rather, I want to use the place I depict as a kind of template or placeholder that allows the viewer to enter and engage with it in their own personal way.

i need a little solitude - 2022, 50x70 in, oil on canvas

Scharoun aimed to make the house a fun experience for children, “incorporating slides, hatches to climb out of, and colorful peepholes.” You've said that in your work, you express the feelings you experience when visiting a location by “exaggerating reality.” How did visiting Haus Schminke personally impress you, and in what ways did these impressions influence the amplified personal touches you've added to these paintings?

The house is a coherent overall composition with lots of fun little details that you stumble upon. It must have been especially fun for the children of the house. Scharoun manages to awaken the visitor's own childhood memories, and to create a place that is functional, livable, beautiful, and yet does not take itself too seriously.

As with my previous work, I made the decision to dedicate a series to this place intuitively, on location. When I paint, I try to trace the feeling I had when I visited the place. I use the photos I took of the location as digital sketches which I edit continuously over an extended period of time, in parallel with my work in the studio. I move furniture around, add or remove objects, change lighting conditions. I do this until my sketch approximates the memory of the feeling I had during the visit. For me, some objects also serve as surfaces for mental projection. I see certain objects, those I associate with in some way, as being charged in a funny way; they do not carry specific information but do transport feelings.

However, I always subordinate my arrangements to the overall composition, which should convey the basic mood and, in the best-case scenario, make the viewer enter this thought space, look around, maybe get stuck on one or two details, and linger a bit.

the festivities begin - 2022, 30x40 in, oil on canvas

What inspired the exhibition title The Grand Buffet? How does it relate to the work and/or the content of the paintings?

The title of the exhibition is an allusion to the classic 1973 French/Italian film La Grande Bouffe (The Big Feast) by Marco Ferreri. This film is about food and to a large extent about transience of life – motifs that came up repeatedly during my research into the history of the house and the Schminke family.

The Schminkes' noodle factory had been a family business in the Saxon countryside since 1904, and it was mainly thanks to Fritz Schminke that Italian pasta began finding its way into German cuisine from about 1920.

In Haus Schminke, I found it exciting that the kitchen, although small and inconspicuous at first glance, forms the heart of the house, around which all the other rooms nestle. So I decided to paint all the rooms except the kitchen, and to place in all of the pictures “compliments of the chef” and small hints of the kitchen in the form of mini still lifes. I always paint domestic situations in which people may have just been present, but which are now deserted, with only a few objects, such as an overturned glass or burning sparklers, referring to an action that has just taken place. I think of my pictures as stage sets or backdrops in a film. That's how I imagined this new series – as a chamber play. The film La Grande Bouffe is a chamber play, too, but it takes place in an Art Nouveau villa on the outskirts of Paris.

The whole film seems to revolve around food, dishes prepared with the greatest attention to detail, reminiscent of still lifes by old masters. Yet this hedonistic celebration subordinates itself to the overriding idea of transience. The film’s somewhat macabre joke is that four friends meet there to eat until they die. The baroque vanitas motif – “Memento Mori” – is thus very closely interwoven with the depiction of food in the film, a connection that was also inherent in the still lifes of the old masters.

This sense of intangible doom is very present in how I perceive the Schminke House: obviously built with attention to detail and full of euphoria, today it can only be seen in the context of its history and the history of the country, which started World War II shortly after the house was completed. Fritz Schminke’s son Harald was killed on a battlefield and Fritz himself became a prisoner of war. After 1945, the pasta factory was expropriated. Fritz Schminke was considered a war criminal because his company had supplied the Wehrmacht with noodles. The Schminkes divorced and the house was eventually used as a clubhouse for the GDR Boy Scouts until it was transferred to the state of Saxony after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

All the ghosts of history, the celebration of life and the downfall are for me inseparable from this house. But again, I do not want my paintings to bring old ghosts to life nor to retell the story of the house. Instead, I want to create spaces for new stories, in which the viewer becomes the protagonist.

so are we going to eat this tart or what - 2022, 30x40 in, oil on canvas

Visitors to The Grand Buffet are invited to seek out all the hidden and playful elements you have added to the paintings. Do you consider this series to contain some of the most interactive works you’ve created for viewers? What emotions or impressions are you hoping viewers will come away with after viewing?

The series is quite interactive since the individual paintings in The Grand Buffet communicate with each other. Whether this or another series is more accessible to the viewer in this sense, I am not sure. I think this is very individual.

I can say for myself that I am constantly learning; I want to gain experience and further develop my concepts. In the Florida Räume series, for example, I had the idea for the first time to create a fictional place out of many independent rooms. Hidden in all the paintings were little clues that connected one “Florida Raum” to the next. This was a challenge that I really enjoyed. I always try to make my paintings work individually and unfold on another level when viewed as a group or, better yet, altogether as the whole series. It’s one thing to come up with a cohesive image that makes sense compositionally and in terms of content. But when the works happen to function together as another work, it makes me very happy.

This is also the experience I want the viewer to have: through painting, I try to open up spaces in which one can be alone with oneself. When you move from one “room” to the next within the exhibition, you move, so to speak, within the concept of a single house. I do not mean to prescribe or name specific feelings or impressions. I simply hope that my work triggers something in the viewer.

it‘s quite a strange coincidence that you find me here, as I’m rarely to be found in this house - 2022, 40x30 in, oil on canvas

i raise my glass; i do not know for what reason, but i raise it all the same - 2022, 50x70 in, oil on canvas

A fascinating element of this exhibit is the addition of ambient recordings by Brooklyn-based sound artist Daniel Neumann. According to the gallery, “Neumann has composed a series of tones for a 3.1 channel sound system that is invisibly installed” in the space.

These “room tones” alter the background sound of the gallery and mimic the “subtle echoes” of what might happen within your Haus Schminke depictions. How did this dual project come about? Did you collaborate in any way with Neumann on the creation of these soundscapes? How do you think adding these sonic elements may impact the impression/experience viewers have of these works?

Last March, I saw Daniel’s multi-channel audiovisual work Latent Seeds in the group show Forward Ground at Fridman Gallery on the Bowery, and I couldn’t get it out of my head for a long time. A funny coincidence is that Daniel is originally from Saxony, where Haus Schminke is located. Little by little, the idea of a collaboration with the sound artist grew on me. As I mentioned, I think of this series like an intimate chamber play without a plot and treat the individual works almost like sets in a film. Daniel has created a spatial atmosphere for my paintings while simultaneously situating them in the gallery space.

I am very happy and grateful that Daniel agreed to do this, and I am extremely satisfied with the result. Although we exchanged ideas intensively and developed them together, I was not involved in the recording of the sounds or the installation of the soundscapes. It was important to me that it not be a commissioned work of mine, but a collaboration of two different mediums. It’s almost a bit spooky how the two component parts – the paintings and the sounds, as different as they are – have certain parallels and magically intertwine into a new whole.

it’s not necessary to act like a beast at the dinner table - 2021, 30x40 in, oil on canvas

what must we do to amuse you - 2022, 40x30 in, oil on canvas

Prior to the opening of The Grand Buffet, you had a three-month studio residency in Beacon, NY. What do you love most about working in Beacon and the Hudson Valley? How do the surroundings and environment influence your approach to creating or any other elements of the work you produce there?

I don't think I'm exaggerating when I say that the time I spent at Beacon was the quietest time of my life as a painter, in the best possible way. I also now perceive and understand the concept of “residency” quite differently. There are two factors that I miss as a painter in Munich and therefore appreciated all the more in the Hudson Valley: time and space. I think this is probably the case for most contemporary artists who live and work in larger cities. A quiet place on the water surrounded by beautiful nature sounds almost too good to create serious contemporary art. One might think that it lacks creative tension or an argument; what can be created in a place like this besides kitsch? I disagree completely.

The proximity to New York City and three other states, as well as the many artists who have moved out of the city to the Hudson Valley in recent years, provide the opportunity for conversation and discourse – if you look for it.

In terms of inspiration, Beacon has been the launching pad for a number of field trips –Dia, Magazzino, Storm King Sculpture Park, and even Pennsylvania to see Falling Waters and other Frank Lloyd Wright houses…

The Grand Buffet is on display at Fridman Gallery in Beacon, NY through July 24

Read our interview with Alina from December 2020 about her Fridman Gallery exhibit Sculpting in Time

Tyler Nesler is a New York City-based freelance writer and the Founder and Editor-in-Chief of INTERLOCUTOR Magazine.