PHILIPPE LABAUNE'S narrative journeys

Photo by Christina Poindexter

Founded in 2020, Philippe Labaune Gallery focuses on graphic design by featuring high-level artists whose common point is to explore new territories and to decompartmentalize the borders separating various modes of expression: illustration, painting, comic strips and animation.

The gallery is currently showing nar·ra·tive, an exhibition of illustrations and strips created by twelve artists from Asia, Europe, and the United States. It runs through September 3, 2022. All artwork images shown here are currently a part of the exhibition.

In this interview, Philippe Labaune talks in-depth about his lifelong passion for narrative art and how he came to start his gallery after a long career in the finance industry.

Interview by Tyler Nesler

Edited by Assibi Ali

You’ve had quite a unique life trajectory, going from a 25-year career in finance to opening what may be the only US gallery specializing in high-end narrative art and illustration. The intermingling of art and money seems like a sensitive topic for some people, but do you feel like there are elements of risk-taking and savviness in the finance world that have ultimately helped you navigate the business side of the art world? From a business perspective, what are some differences and similarities you see between the finance and art worlds?

It’s fair to assume that a background in finance is advantageous to running a business, but there are always pros and cons. There is a big difference between the basic concept of money when you’re running a trading desk on Wall Street versus being a business owner. Finance is a fast-paced world in which the “problem-solving” quality of an individual or team is measured on a daily, if not hourly, basis. Some of the most intelligent people I know on the Street are brilliant short-term shakers and movers. But that doesn’t necessarily translate into success in setting up a 2-or 3-year plan for a given project. Constructing an exhibition or preparing for an art fair requires a lot of logistics and future thinking. You do not need to reinvent the wheel each time, but it’s paramount that you keep an open mind, lest you run the risk of your gallery’s artistic line-up becoming stale.

That is not to say the skills I’ve accumulated have no place in the art world. Concepts such as “staying power” or “treating your customer as you would like to be treated” stand across any type of business. Where it differs the most is in the feedback. Most of the time, you have immediate feedback in the world of finance, where it’s likely to have a dollar sign in front of it. Art spaces do not function as such. I’m a believer that money is the “nerve of the war,” but the success of an exhibition cannot be measured solely in terms of sales. You must learn how to cultivate a relationship with both first-time buyers and savvy, long-term collectors over an extended period if you’re going to suggest the right art to suit their tastes. That requires a degree of intuition and emotional intelligence that you are not going to be taught on the trading desks on Wall Street.

Philippe Labaune Gallery on opening night of nar·ra·tive

You’ve long had a passion for and collected this type of work - what are the origins of your attraction to narrative art and illustration? What was the first comic art you saw that really spoke to you and made you want to keep exploring the form and discovering more of its masters?

Growing up in France in the 70s, bandes dessinées (the French term for comics) were found everywhere you’d turn. As a kid, it started at home. My parents read comics and subsequently passed them along to my three siblings and myself. They were true aficionados of the Franco-Belgian school, which allowed me to start with the classics. From the famous “clear line” of Hergé’s Tintin and Edgar Jacobs’ Blake and Mortimer to the less regimented Marcinelle style of artists such as André Franquin or Jean Roba, the Franco-Belgian BD’s were my entry point into the marvelous world of comic books.

At the time, the medium was in full resurgence as new styles and subject matter gradually became more mature in content. My older brothers aided in my discovery of the sci-fi, violent and erotic sides of comics; they introduced me to the superb Jean Giraud and his western series Blueberry, Hugo Pratt’s Corto Maltese’s poetry, Tanino Liberatore’s ultra-violent RanXerox, in addition to plenty of other work, the memories of which I still hold close to my heart.

Ultimately, my unyielding passion for comic books stems from a tragic loss. I lost my father and one of my brothers in the span of a few short years, and comics became my refuge and safe space during that period of grief and mourning. I truly believe that they offer a very therapeutic experience in the sense that no other medium at the time offered such an on-demand evasion from reality, whether it’s for two minutes or two hours. Personally, I can count five traditional books that I have read twice as compared to hundreds of comics that I have read hundreds of times over.

Mathieu Bablet, Tribute to Moebius, 2022, China ink and watercolor on paper - Framed: 20 x 16 in

Georges Bess, Frankenstein - Page 8, 2021, China ink on paper, 22.75 x 18.25 in

Ian Bertram, Muse, 2022, China ink, acrylic & pencil, 76 x 52 in

After leaving finance, you established the association Art9, intending to introduce the American public to European comics; then, in early 2020, you organized the first major exhibition of original European comic strips in the U.S. at Danese / Corey gallery (Line and Frame: A Survey of European Comic Art). What was the impetus for you to begin professionally showing comic art? Was it something you had always dreamt of doing?

The comic book industry wasn’t always as large and highly valued as it is today. I began collecting original comic art in the late 90s, back when there was only one specialized gallery in Paris. It was a small space, and the artwork was often just pinned onto the walls for display. On special occasions, some libraries would organize short exhibitions of original strips in anticipation of a book launch. The market was small but steadily growing over time; more collectors started to pop up around the early 2000s, as well as a couple more galleries opening their doors in Paris and Brussels.

However, it’s one particular auction in 2007 that I firmly believe changed the scene and caused a permanent shift in the market. Famed French artist Enki Bilal showcased about 20 pieces at Artcurial Auction House and the prices absolutely exploded. Everyone in the room walked away, realizing that something special had just happened before them. Today, there are seven comic art galleries in Paris alone. Three in Belgium, two in Italy, and now mine in America; all of us showcasing original strips and illustrations.

What pushed me the most to open my gallery was, ultimately, a need for convenience. In Europe, many auction houses have one or two annual sales dedicated exclusively to comics. These are proper auctions where, prior to the sale, the public can visit and admire the artwork in a finely curated space. As a collector living in New York City, it quickly became frustrating that there were none of the specialized galleries I was used to. Instead, the only way to purchase original strips was to either fly to Europe or find them online. Call me old school, but the online buyer’s experience leaves much to be desired when you’re unable to view the pieces with your own eyes. Many times, I’ve been disappointed by an online purchase; from the color, the description, and the physical state, it can be quite difficult to ascertain the quality of an artwork bought online. For many years, I thought to myself that there should be such a gallery for comic art in the city.

It’s when I decided to leave the world of finance in 2019 that I had made up my mind to find a space to showcase the art that I, and many others, so fervently sought after. At first, I decided to set up a pop-up show and test the waters with a survey of European comic art. We showcased over 50 artists and had the privilege of being the first in the United States to present two original strips from Hergé’s Tintin. The show ran for three weeks in February 2020, and we finished up a successful viewing just prior to the closures brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic that following month. We welcomed over 2,500 guests amongst a plethora of rousing media responses from reputable organizations, including NPR. Despite the beginning of the pandemic and the damage to the economy that followed, our institutional clients came through, and I am very fortunate to say the exhibition was a financial success.

Avitz (Avi A. Katz), City Mouse - Levinsky Market, Tel Aviv, China ink, chalk and marker, 20.5 x 39.25 in

Jonathan Barravecchia. The Long Yesterday (Tribute to Moebius), 2022 - China ink, oil and watercolor - Framed: 22 1/2 x 53 in

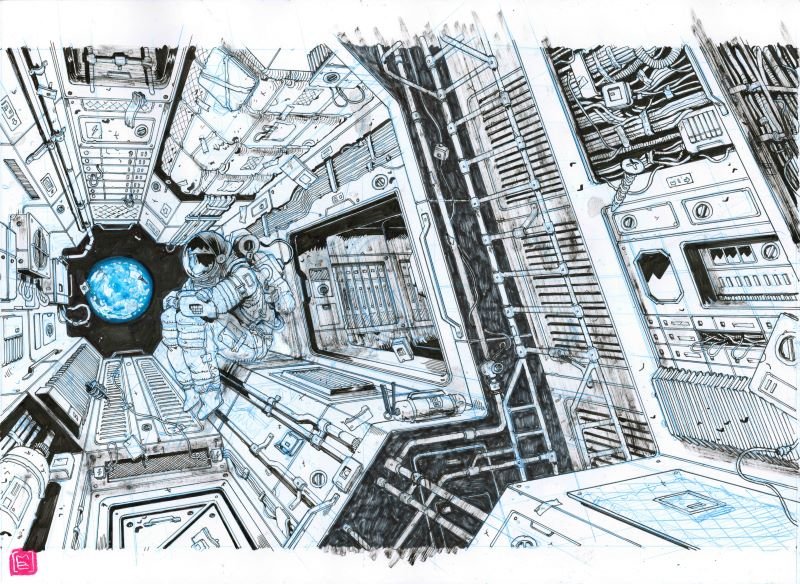

Mathieu Bablet, Couverture Manga - Planet, 2022 - Inactinc np and china ink on paper - Framed: 15 1/2 x 20 1/4 in

What challenges have you encountered in getting serious US art collectors and art industry interest in this type of work? Why do you think it has taken so long for this form to be taken seriously in the US versus Europe?

I go back to the basic principle of any “niche” business: it’s a marathon, not a sprint. There are a variety of challenges that our gallery will need to overcome, much like any business treading somewhat uncharted territories. But the market for comic art and illustration is slowly transforming in the United States. There are collectors who seek a particular page of a particular superhero drawn by a particular artist at a particular date, and there are people who enjoy comics but more deeply appreciate the structure, technique, and diverse storytelling capabilities of strips.

More and more comic book artists are exploring new mediums such as acrylic, stencils, mixed media, and more to create larger pieces from strips, covers, splash pages, etc. Indeed, many artists who create larger illustrations, whether for commissioned work or as part of their own personal series, are opening up a new market before themselves. When you take a comic artist away from strips and the editorial limitations on storytelling, rhythm, and pleasing the publisher, and instead let them craft the narrative to their unique vision, that is where the magic happens.

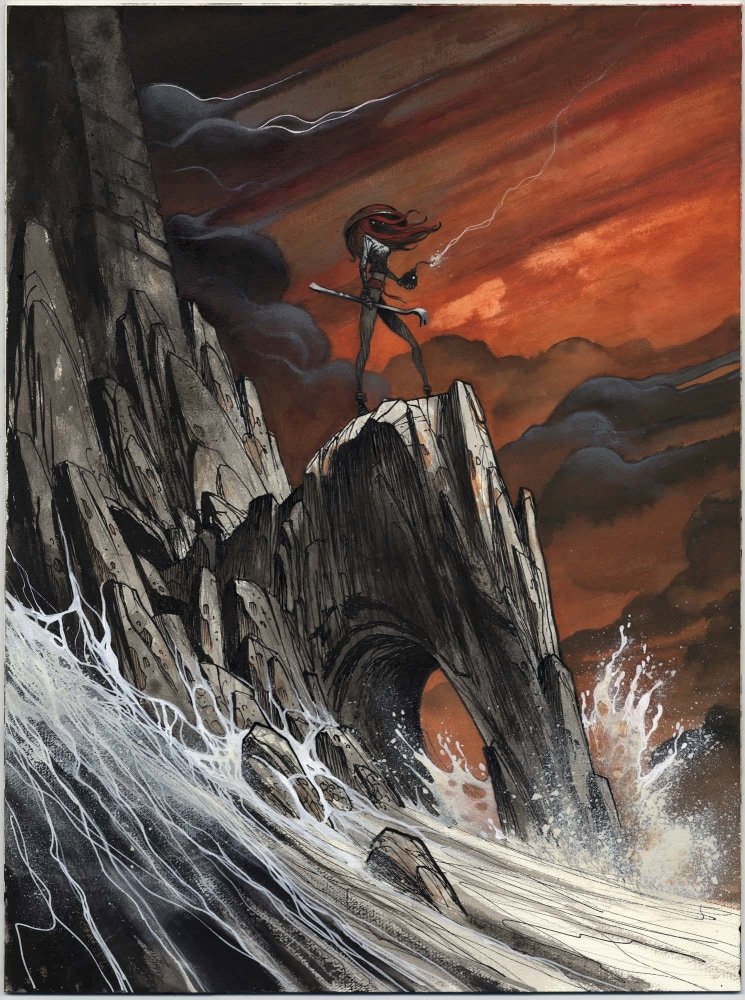

Didier Cromwell, “Souffler n’est pas jouer” - (Page 44 of 3rd Album: “Journal d’une Emmerdeuse”/ Ed. Akileos), 2017 - Acrylic and china ink on Fabriano paper 300gsm - Framed: 25 1/2 x 19 1/2 in

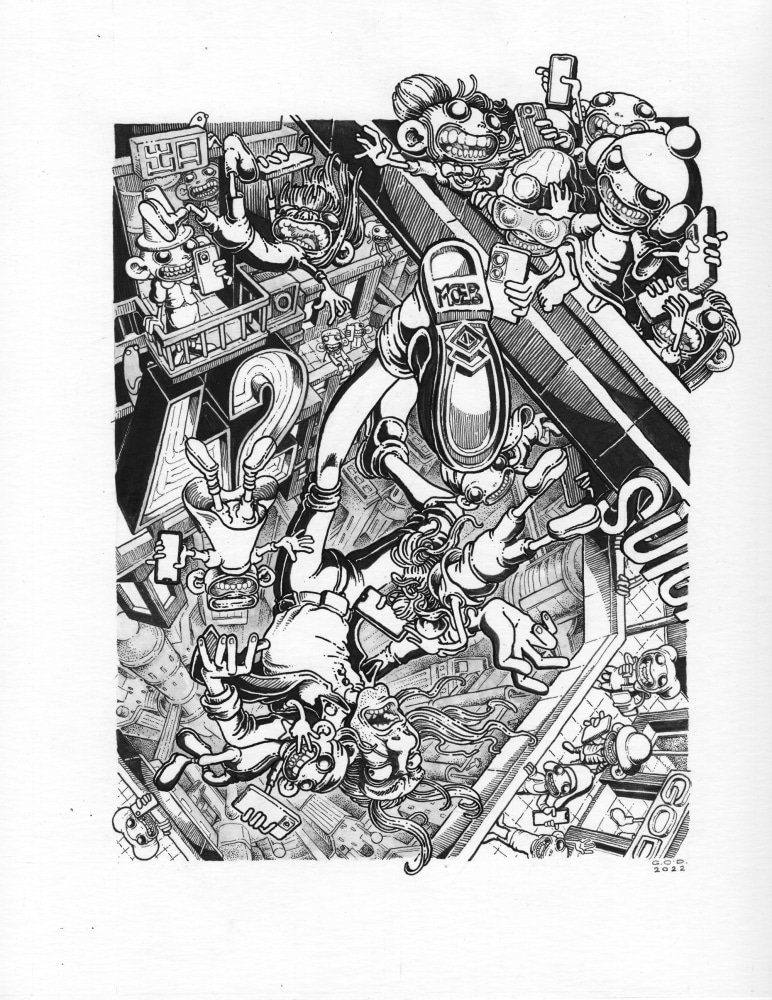

Carles Garcia O’Dowd (carlesgod), Suicide Avenue, 2022 - China ink on paper - Framed: 13 7/8 x 11 in

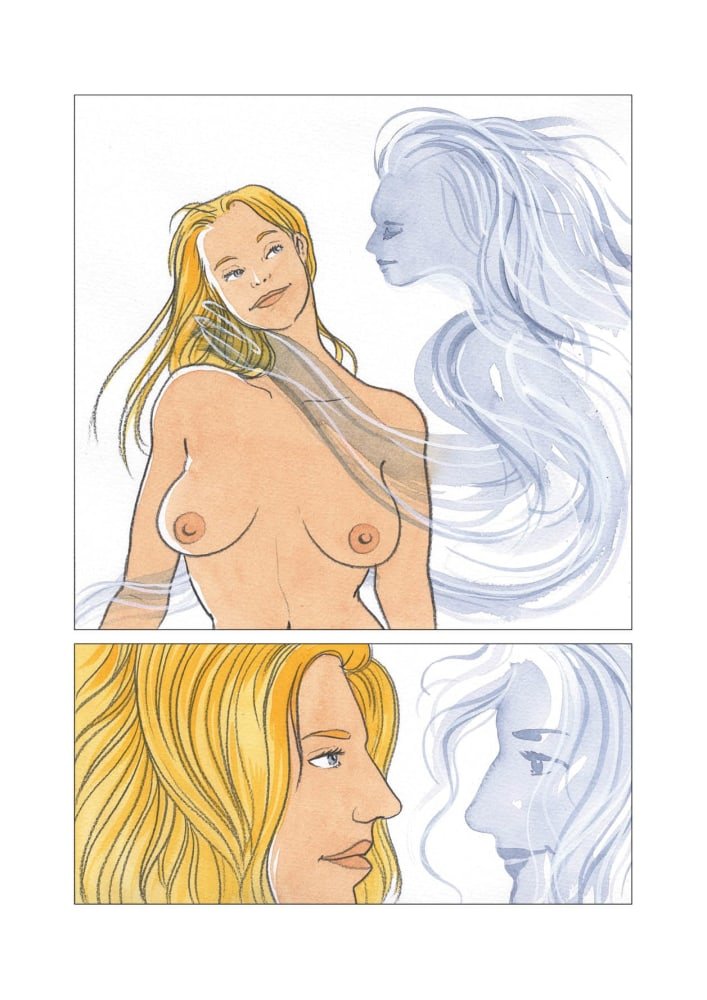

Alain Poncelet, Morphea (Zoe) Page #8, 2021 - China ink, pencil, and watercolor - Framed: 20 x 14 5/8 in

Your gallery's current group exhibition, nar·ra·tive, is your space's most ambitious show to date. Featuring twelve artists from Asia, Europe, and the US, you've set out to showcase works that give a good introduction to artists from different cultures, backgrounds, and training, along with highlighting the recurring theme of your gallery: “storytelling through images.” What were some criteria you had in choosing these twelve artists? In a way, do you view this show as an extension of the Line and Frame exhibit because it is a further comprehensive introduction of this form to an American audience?

The summer group show is, at its core, a celebration of comics. We intentionally chose a flexible theme to give the space for more artistic freedom, rather than presenting something more rigid and specific. Regarding the selection of artists, that criteria is much more personal. Sometimes, you have the opportunity to showcase works by new and emerging artists who perhaps have yet to have the fortune to have their work presented in New York. For more established artists, we can present new artwork that wasn’t originally showcased as part of their solo exhibition.

I realized early on that having to create a specific theme can sometimes be restrictive for some of the artists. The only question asked of our artists is if they would be interested in doing an homage to another artist; a respectful and beautiful act of celebration. This year, the most prominent homages are dedicated to comic legends Frank Miller and Moebius. The most important factor we considered when developing this summer's group show was to ask ourselves, “How can we push the envelope and truly make it something special?”

Mor (Stencilart), Wolf, 2020 - 2022 - Hand cut yupo paper, acrylic paint, gouache, wax pastel, colored pencil, ballpoint pen - Framed: 71 x 33 3/4 in

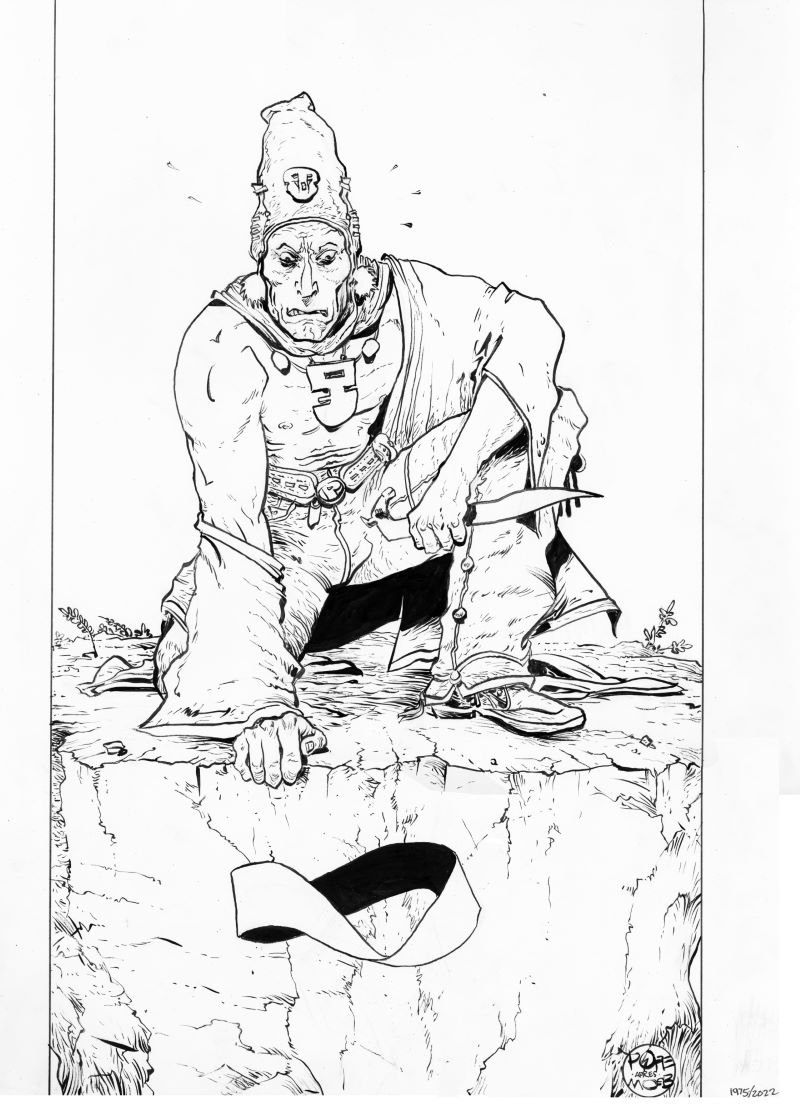

Paul Pope, Friendship, 2022 - China ink on paper - Framed: 26 x 21 in

Paul Azaceta, Homage to Moebius - Monsieur Giraud, 2022 - China ink and gouache on paper - Framed: 35 1/4 x 43 1/4 in

nar·ra·tive must have presented some challenges in how to feature all of the various works in your gallery space in a manner that flows well for visitors. Since “narrative” itself is a topic of the show, how did you conceptually approach the arrangement of the art in the relatively small spaces/annexes of your gallery? Were you consciously thinking about how a person might move through the space and see the works as a kind of journey or narrative in and of itself?

Visual presentation is naturally the top priority for any art gallery worth a dime. In the case of nar·ra·tive, we tried to play to the strengths of each artist. Artists like Mathieu Bablet and Didier Cromwell are known for their dynamic and carefully detailed illustrations. Ian Bertram is a highly established comic artist who's been shifting into much, much larger and more personal illustrations. Jonathan Barravecchia's strengths are in his use of watercolor and the way his work can bounce between both light and dark. The front room, when you walk into the space, shows four uniquely distinct but equally powerful styles from the aforementioned artists, announcing to our guests that they’re being welcomed to a very diversified exhibition.

In our middle room, we have a space dedicated to Moebius, with four homages from four different artists lining up the wall. Paul Azaceta, Paul Pope, Carles Garcia O'Dowd, and Mathieu Bablet pay respect to the legendary Jean Giraud and several of his influential works. References to the Arzach, Blueberry, The Fifth Element, the Silver Surfer, and more are scattered throughout and show how deeply these four artists internalized the work of Moebius and the continued influence he’s had on those who succeeded him.

If we’re fortunate enough to have a selection of strips to present on our walls, then we’re keen to showcase them in a way that preserves the original story as intended by the artist. In the case of Alain Poncelet and the strips from his self-published book, Morphea, we carefully selected six pages to frame for the wall. The pages are not directly sequential to each other as they appear in the book, but you would hardly be able to tell thanks to Alain’s strength at capturing facial expressions and body language. Those six framed artworks tell a story that’s easy to follow along with and almost always gets people to stop and admire the visuals put together.

We reserve the back wall for our most visually captivating work, and for this exhibition it’s Mor’s Wolf. A labor of love that demanded over 150 hours of her efforts, Mor carefully cut and painted a large, stunning piece that represents her wild and intuitive approach to creation. The hand-cut stencil is propped just slightly in the frame to give a bit of depth to the illustration, with the artist opting for a classic Hermes orange background to contrast the light blue, black, and orange colors in the piece. Its placement means you can’t walk past our gallery and peek through the door without seeing the bright spectacle ahead of you, and it’s one of the most magnificent pieces we’ve had the privilege to showcase on the walls of our humble gallery.

In September (2022), your gallery will be participating in the Art on Paper fair in New York - could you talk a little about which artists you will be showing there and how you believe your gallery fits into the fair's theme in general?

Art on Paper will be our very first art fair, so our approach is to be mindful towards mitigating risks. I’m cautious about presenting too many artists because the booths at an art fair have such limited space. Often, the most detrimental risk would be having a mismatch of artists where it becomes too difficult for any piece to stand out.

We will showcase new works by Miles Hyman and Lorenzo Mattotti, both of whom we exhibited in 2021. On display will also be three works by the emerging Bosnian artist, Miroslav Sekulic, who is presently residing at the Cite d’Angoulême (the French Cultural Center for Comics). His latest graphic novel was masterfully painted with acrylics and showcases absolutely mesmerizing detail that translates beautifully onto a larger canvas.

One of the organizers from Art on Paper informed us that we just may be the first ones to present original comic strips and illustrations at this fair. Isn’t that kind of exciting?

Tyler Nesler is a New York City-based freelance writer and the Founder and Editor-in-Chief of INTERLOCUTOR Magazine.