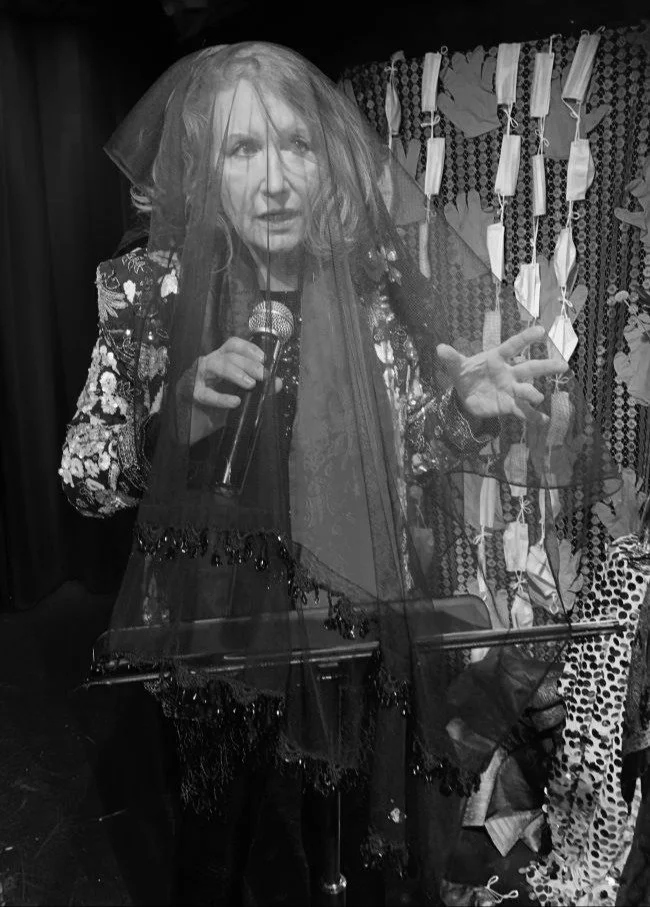

Censored? Shadowbanned? Elizabeth Larison of the NATIONAL COALITION AGAINST CENSORSHIP Discusses How to Fight Back

Elizabeth Larison has worked in curatorial, programmatic, and directorial capacities for arts organizations and venues such as Flux Factory, the Park Avenue Armory, the Vera List Center for Art and Politics, and apexart.

Larison is the Director of the National Coalition Against Censorship’s Arts & Culture Advocacy Program. In this interview, she talks in-depth about leading initiatives in advising and educating artists, writers, playwrights, curators, and other cultural intermediaries on how to address the presentation of controversial works.

Interview by Logan Royce Beitmen

Thank you so much for joining me, Elizabeth. You direct the Arts and Culture Advocacy Program for the National Coalition Against Censorship. Give us a brief overview of the work that you do.

First and foremost, we’re driven by the belief that artistic freedom is a critically important human right, and that it's as essential to culture as it is to a thriving democracy. We believe that when art provokes or offends, calls for censorship can often arise, but artistic provocation and offense should be met with critique, contextualization, and discussion, not with censorship. So, to that end, the program activities that we oversee include one-to-one censorship case intervention. That means I learn about potential censorship cases, or they get reported to me, and I reach out to the people involved. Sometimes, that's the artist, sometimes, that's the curator, and sometimes, I'm working with the institutions, often behind the scenes, to try to influence or educate about best practices in terms of showing contested works.

When that isn’t enough, sometimes we engage more publicly. That might involve things like statements and letters, for example. We also have an annual curatorial workshop, which is focused on providing resources to curators. Curators are important gatekeepers who often bridge the gap between the artistic practices and intentions of the artists and engaging with the public or particular communities. The curatorial workshops were founded in 2015 to help embolden curators and to help them network with each other to determine best curatorial strategies for dealing with these challenges.

We have an array of resources for artists, curators, institutions, playwrights, and anyone looking for ways to uphold artistic freedom in their work. We also are part of a project called Don't Delete Art, which defends artistic freedom in online spaces.

A lot of people are familiar with the ACLU and the work they do to fight censorship in the courts, but you take a different approach in that you're not working in a legal framework usually.

That's correct. We are not a litigating organization, and, as you've probably learned, I'm not a lawyer. I am trained in curatorial practices and studied human rights issues as an undergrad. Our approach is one of education and advocacy.

Also, the conditions around which we get involved in a case are not solely based on whether they transgress the First Amendment, but rather we go beyond to protect and uphold free speech principles. First Amendment law protects private citizens from censorship from the government. But in the US, censorship can happen from private actors as well as public governmental actors. A private museum or a nonprofit institution can legally censor. It's their right to present work that they see as fitting their institutional mandate. But where we get involved is trying to uphold principles of artistic freedom or principles of freedom of expression, because they are just as crucial to a thriving culture as they are to a thriving democracy.

Let me just give a brief overview about why we were founded, because it's interesting in the context of you having mentioned the ACLU. NCAC founded the Arts and Culture Advocacy Program [ACAP] in 2000, right at the end of the so-called culture wars of the 1980s and 90s, at a time when programs focusing on artistic freedom were closing down because it was believed to be the end of the culture wars. The ACLU had such a program. The National Campaign for Freedom of Expression had such a program. People for the American Way had such a program. Those were all closing. So, ACAP was founded to fill that void. To date, we remain the only national project dedicated to upholding artistic freedom in the United States. That’s an important qualifier because obviously censorship around the world is a big deal, and it has catastrophic life-threatening consequences for people, depending on the country, but because of the First Amendment, people aren't jailed here just because their art is controversial. They do have works canceled or exhibition opportunities withdrawn, and that has a very real impact on the fabric of what we can engage with as a culture and as a society.

I just spoke with Danielle SeeWalker, who had a residency canceled due to her political beliefs. I know you worked with her. How did you help her?

We reached out to her after news broke about her residency cancellation. I know that this will be detailed elsewhere, but to the extent that it's relevant here, I'll just say that she was invited to do a residency that involved the creation of a mural, a public talk, an exhibition of photography that she'd already made, as well as a workshop. In the weeks leading up to the residency—I think less than a month before it was supposed to begin—it was canceled, all because there had been some concerns about an artwork she had made for a completely different opportunity. It was one artwork that had political overtones that made the city nervous. They somehow conflated that with some perception that she would then politicize the public art program in the town of Vail, Colorado.

Danielle SeeWalker

They said they were concerned she was going to politicize their program, but weren't they the ones, in effect, politicizing it by taking this action to cancel an artist for her political views?

Absolutely. And that's something that we see often. Institutions claim that a work is inherently controversial or inherently problematic or political or divisive. They remove it, thinking that's going to solve whatever problem they anticipate having. But, in the process, they position themselves in the role of the critic, which is not neutral. It’s a political decision. It is a decision to remove or oust a particular idea. And that often draws far more attention and controversy and blowback than if the project had gone forward.

In the case of Danielle, I think what might've made the town the most nervous was the mural commission, because it was going to be a new work. But there's typically a process in place for murals like that—a proposal process and parameters for review that are put in place. When I spoke with Danielle about this in an interview, which is on our website, she said it's standard for her to ask what's off limits, what does the town want, and to work with them. But that opportunity had been completely pulled out from under her, which is infuriating, and it sets a terrible example, in which institutions act as if it's okay to do a full political litmus test on everybody that they work with.

What actions did you take on her behalf?

We wrote a public letter to the town of Vail. We shared with them our best practices. We expressed our concerns that they were exercising viewpoint discrimination, which, as a government-run art program, they cannot discriminate against viewpoint. That is a First Amendment concern. So, our letter was to advocate for Danielle, outline the wrongs that we saw, and encourage them to adopt criteria and procedures for review that would protect political expression among the artists. We also did an interview with Danielle to better share her story and outline what we saw was so concerning about it, namely that an artist was somehow de-selected for their creation of a work that was not relevant to the artistic opportunity at hand.

You also added her to your map, “Art Censorship Index: Post-October 7th.” Could you explain what that is?

Absolutely, and thank you for mentioning that. We added Danielle’s censorship incident to our Art Censorship Index: Post-October 7th, which is a resource that monitors incidents of censorship of artworks or cultural presentations, including talks that have been canceled, because of how they are perceived to comment on the present war in Gaza or historical conflicts between Israel and Palestine. This is important, because the controversy or discussion around Israel and Palestine is often taboo, and there's a lot of conflicting opinions about it. Censorship around these issues is not new. However, obviously, in the past year it's really exploded, and we feel it’s an important thing to document. We created this map to do just that, because ACAP is a very small project. It's a very small team—I'm the only full-time employee for this project—so I cannot feasibly write a letter for every single incident of artistic censorship that's happened in the past year. This is meant to be a resource so people can understand the breadth of the problem, because there's been a real explosion in censorship of artists in the past year around this issue.

We don’t claim to keep perfect data on all artistic censorship in the US at any time, because censorship is naturally something which is done behind closed doors. We only find out about artistic censorship in many cases because one person just speaks up and wants to know what they can do.

So, you’re saying there's probably a lot more censorship than what’s recorded on the map, because you can only include what people happen to report.

And people have to know about us to be able to share it, or it has to be reported on by a news source, and that doesn't always happen. So, a big part of my job in the time that I've been with NCAC has been to try to raise our profile and make sure that artists, curators, and institutions are aware of us, to know that we're here to support artistic freedom, and for all of the actors involved in the showing of artwork to have the tools they need to do so productively.

So if an artist feels that they've been censored or they're facing the threat of censorship, what should they do?

There's a Report Censorship form on the NCAC website, and that stands as a catch-all for any kind of censorship that people might be experiencing, including art censorship. So, by all means, reach out to me, and we will assess what advocacy options are available.

Generally speaking, it's important to understand the conditions around which your work as an artist is authorized to be shown in a particular way. Has it been invited or accepted? Did you apply to an open call, and the work was selected? Are you in advanced conversations with a curator or a venue, and there's no sign that there's a reason to not do the show or the project until suddenly it's canceled for a fear of a backlash or controversy? Those are some of the preconditions around which we can consider a censorship case. We can't really consider censorship that happens before the decision-making process is complete, because curators and institutions are always in a process of selection and rejection, and not being chosen in an open call or not being chosen to be shown in particular museums is not really a clear sign of censorship. But assuming there's a reasonable understanding that your work has been invited or wanted but then is suddenly dropped, you’ll want to try to get a sense of who's behind that pressure. Is it the membership or staff or board of an institution? Is it a political appointee or public servant? Typically, censorship comes from people in power, particularly those who control institutions.

I know an artist who's a pro-Palestine activist, and she told me that her name appears on a McCarthy-style blacklist, which she says is being circulated by a prominent art collector—so, a powerful person, but a private individual, not an institution. The same collector pressured a gallery in Europe to cancel an exhibition of hers. I'm wondering, first of all, are blacklists illegal? And what can we do about them?

The activities you described of a collector trying to pressure a private gallery's curatorial decision or exhibition program are not inherently illegal, even though, if effective, it would have censorious effects, because it serves as an attempt to override the curatorial decision-making of the gallery. This goes back to the idea I mentioned earlier, that just because something is not illegal doesn't mean that it can't have censorious effects. If this collector is indeed successful, they will be contributing to art censorship. Censoring because of an artist's politics, or the political content of the work, or even the identity of the artist, limits the art that people can engage with.

What can be done about it is, frankly, the work that we're doing at ACAP every day. That includes encouraging cultural institutions to adopt statements of artistic freedom that recognize that they might not endorse or agree with all the positions that the artists themselves take or that might be gleaned or interpreted from the artwork. If you think about it, this should be a given in most cases, because in what museum, if you look at the history of all the work they've ever shown, can you assume that all of the art is representative of the museum’s position? That's not possible, because there's so many artists, and they're not in agreement with each other, right?

Along these lines, the NCAC supports free speech regardless of the political content. For instance, the Art Censorship Index: Post-October 7th map includes many examples of artists who've been censored for pro-Palestine views but also people like Matisyahu, the rapper and singer, who’s had concerts canceled because of his pro-Israel views.

I'm wondering, do you ever find it challenging to maintain a nonpartisan stance, supporting artists who may be ideologically opposed to one another? Do the artists themselves ever express frustration with NCAC for not taking a stronger stance one way or another on divisive political issues?

Well, as a free speech organization, we're here to defend people's right to express what they want. Maintaining a nonpartisan stance is essential to the principle of freedom of expression, and that goes back to the very real idea that if we silence one group of people or ideas because they are unpopular or unliked, that renders the opportunity for that same censorship to happen to other opposing voices in the future, because power is always shifting.

It's easy to oppose censorship when people I like and agree with are being censored. It’s harder to oppose it in general.

Yes, and I think the hard work of defending freedom of expression is recognizing and being willing to entertain your own predilections and what you are inclined to agree with, and recognizing what can so easily happen if the tables turn and a different entity is in power. Working by that principle is key to this work. Sometimes, it can be challenging, if one has to defend the right of a speaker to have an idea and perspective that might be different from one’s own.

I haven't heard specific criticism of your organization, but I know other organizations, including PEN America, have been criticized by some pro-Palestine activists for not taking a stronger stance on Gaza. It seems like NCAC’s position is that remaining nonpartisan is what gives you credibility, especially since you are not a legal organization but one that operates in the court of public opinion.

Exactly, and that's critical. I don’t want to talk about other groups, but you hit on something very important, which is that our work is not to be partisan. It is to be principled and to recognize that the inclination to silence somebody you're not in agreement with is, in many ways, an authoritarian impulse. It’s one of control, and that is antithetical to principles of democracy, which makes room for disagreement and debate. I think about that a lot.

You mentioned NCAC’s Don't Delete Art campaign, which calls attention to the censorship of art online and in social media. Because of the way platforms like Instagram operate, using blackbox algorithms that are completely opaque to users, it can sometimes be difficult to prove that censorship has even occurred—for instance, in the form of downranking or shadowbanning. How can we combat these new insidious forms of censorship?

What you mentioned were part of the original reasons for the creation of Don't Delete Art in 2020. At that time, artist accounts were being deleted in droves. This was during COVID, when much more artwork was suddenly being shown and shared online. Suddenly, you had a tech company becoming one of the main platforms through which art and culture are shared, which was a major transformation. Content moderation policies—which social media companies have every right to have, and which are generally useful for users on their platforms— become a de facto filter through which artwork is accessible. That became a very big problem, particularly in cases where artists were suddenly finding out that certain images won't be posted, or they're finding that their accounts have been deleted. So, we advocated, very early on, that there need to be appeals processes that are clear, so if artists believe that they are not violating the content moderation guidelines, they can make a case for themselves or ask for human review. Given the size and scope of Instagram, or social media in general, there's too much reliance on AI algorithms to identify whether content violates the guidelines.

I think it was in December, 2023, that Instagram, which is one of the most popular tools for artists, announced their Recommendations Guidelines in response to questions about shadowbans. Before December of 2023, artists would just notice that certain works were not being seen by their followers. Certain works would just not get the traction, the likes, or what have you. That was referred to as the shadowban, which is the apparent lack of visibility or engagement that a given artwork can get.

It can be hard to prove. But if certain accounts normally get thousands of views and then suddenly, you look at the metrics, and the content is only being shown to a handful of people…

Right. But what Meta announced in December, 2023, were its Recommendations Guidelines, which gave artists—or I should say all users, but particularly it affects artists—it gives them boundaries around which they understand their content is permissible to exist on these platforms, but it will not be promoted, it will not be recommended to non-followers. So, there have been considerable strides in that realm. There's more information available to artists. But there are still elements of social media policy that are very blackbox, that are not clearly spelled out. So, what else can be done?

One of the things that we do is have an online gallery of artwork that has been censored in online spaces, whether that means it has been downranked, shadowbanned, or removed. It’s an important resource for people to really see what is being hidden. Many times, it is content akin to what you could see in a museum for general audiences. There is no current barometer in the algorithms that we're aware of that considers the artistic context of the work. You think about all of the data that these social media companies and other online platforms absorb about the users. They must know which users are working artists, which users are involved with a particular gallery or museum, and other times even there's context to an image. Is it a drawing on a wall that is part of an installation? Is it part of an art book? The artistic context is not a consideration that these algorithms have. So, part of what Don't Delete Art does is try to put the pressure on social media companies, particularly Meta, to make an allowance for that. We also want to activate and educate artists and the digital rights community. There's not a lot of intersection between these two communities, but the more artists recognize the extent to which a tech company is deciding what gets seen and shared in the arts, that is something, I think, that can motivate people to become more aware and more involved.

If artists have been shadowbanned or had work removed, can they reach out to NCAC and the Don't Delete Art campaign and become part of the online gallery?

Yes, Don't Delete Art has a separate censorship report form, particularly when art is censored in an online environment. So, if you have a post about an artwork that has been taken down, if your website host somehow decides that your artwork cannot be uploaded, or if your payment processor for your web shop for your artwork suddenly says that they can't process payments for this artwork because it doesn't meet their criteria for acceptable financial transactions, then by all means reach out to the report form at Don't Delete Art, because they document the trends as they shift. They have tips for artists dealing with different content moderation restrictions and more. For all “offline” events of art censorship, reach out to me or fill out the Report Form on NCAC’s website.

Do you think we need better laws and regulations to protect free expression online and on social media?

The website companies or the tech companies that host these platforms are all private. For the most part, the Internet is a privatized realm. NCAC does not advocate for more government control over the private realm—private speech, so to speak—and we understand the extent to which content moderation is essential for the functionality of the Internet. Nobody wants to log into their favorite social media app and see a realtime update of the most recent posts that have ever been made. It'd be total chaos. It'd be completely useless for everybody. But we do advocate for the companies to have more friendly policies for artistic freedom.

But if you're counting on these companies to do what's right, voluntarily, out of the goodness of their heart, I mean maybe there needs to be some additional pressure.

Yes. One of the projects of Don't Delete Art, which is a few years old now, is our Manifesto Campaign, in which we are rallying pressure from the arts community, including artists, educators, critics, galleries, and institutions. To the extent that they want to sign on, institutions are very important to putting that pressure on Instagram. I don't know if you're familiar with this, but Artsy does an annual report on the art market and how things are impacting it. And in their 2023 survey, there was a question to gallerists about how they determine who to represent, and, when they're considering new artists, how do they find those artists? Number one was word of mouth, or through the artist communities that they work within—a friend-of-a-friend sort of situation. But number two was Instagram. If that's the number two way that galleries find artists, and gallery representation is a huge marker for artistic success and visibility, and if that's being limited by a technology platform, then there's a problem there. That’s a major art industry/art world problem. That should be concerning to everybody working in the arts. I don’t know that it is. So, part of the Don't Delete Art Manifesto Campaign is trying to rally that pressure. We're still accepting signatures. Of course, the biggest impact for something like that would be to get more institutions to sign on. A lot of institutions don't want to step into the fray and add their names to petitions or to pressure statements like that. But we’re hoping more will do so. It’s an ongoing initiative.

Where does the desire to censor art come from?

I think it has to do with a desire to control. Sometimes fear is involved, too. Fear of loss of control. That seems a big motivator in a lot of the cases that we see.

Most people who are wanting to censor art and literature now aren’t coming out and saying, We don't believe in free speech. They might say something like, We want to protect children. Many of these people are probably sincere and think what they’re doing is right. But it’s still based in fear.

I think that that's right. I also think censors often think in binaries. They presume that they know the full extent of the position or interpretation of a given artist or artwork. I would hope that as a society we can understand the importance of engaging with ideas that we find most important, because there is a need to learn about these ideas, to understand where they come from, and also respond to them. Otherwise, if there's a moratorium on a discussion about touchy subjects or ideas that some people disagree with, then it doesn't mean that those ideas are going to go away. It means that they're going to continue to grow in their own siloed state. Then we have these cultural and political divisions where people just don't talk to each other. Arts and cultural institutions are among the only venues in which people can come together from different perspectives and experience something new and be challenged. I think it’s important in our society to have that.

Yeah, absolutely. You talked earlier about what artists can do if they're being censored, but you have resources for curators and arts administrators, as well. If someone is at an arts institution and being pressured to censor art, what can they do?

I think every situation has its case variables that might necessitate different approaches, but from a curatorial perspective, there are ways that curators can prepare for anticipated pushback in regards to their decision or desire to bring in certain artists. That might involve being aware of the institutional culture, what sort of mandates or restrictions they have in place, and making sure that the work that's been chosen clearly meets the agreed-upon curatorial approach, which has been presumably accepted by the institution. I think being aware and doing research on the artwork, on the artist's intentions, and on the historical context, and making sure that these elements are clearly presented with the work as part of the curatorial proposal and as a part of the presentation of the show, are often very important. Similarly, being aware of the institution's key stakeholders and audiences and anticipating who might have questions, who might be vested in particular interpretations of the work, and then being ready to engage them—to acknowledge, and if there's room, incorporate surrounding context in which the work might be read. It really changes case by case, and there's a fine line that a curator has to walk, which is balancing the vision and the intention of the artist, and also recognizing that art doesn't exist in a vacuum. It is part of the world in which we live.

The institution might also have to do outreach and PR campaigns to manage the controversy.

Absolutely. That's part of our Museum Best Practices for Managing Controversy, which is a resource that we created with an array of different national arts organizations, which is meant to be a guide for these institutions to handle difficult conversations about artists. Part of the preparation involves creating alliances, doing advanced research to know who your communities are and anticipate what their concerns might be. This doesn't mean that you don't show something if you're afraid they won't like it, but finding curatorial strategies and tactics to meet those concerns, or to take them into consideration at the very least, through programming or through an array of other approaches. It might mean having a very intentional introduction and education for front-facing staff, making sure that museum guards are aware of the work and are prepared for questions about it. Obviously, the educational programs at these institutions are very important, as well.

How did you come into this role? I know about your curatorial background, but had you done this kind of outreach and advocacy work before?

Yeah, in my earlier work, I had worked with curators on projects around the world, and in certain exhibitions, it was very clear that they might need to translate certain curatorial texts differently in their home country’s language in order to not draw the ire of their governments.

Could you give a specific example of that? If it’s not too touchy of a subject.

There was a feminist exhibition in Iran, for example. And there was an exhibition in Indonesia that had to do with artists who were imprisoned because of drug charges. So, I had to navigate these different situations and recognize the oppression that a lot of people face around the world because of their governments. That was really moving to me. I think my background, educational trajectory, and interests always involved the arts as they intersected with human rights and civil and political rights. Those have always been very strong interests of mine. So, as long as I've known about the National Coalition Against Censorship and its Art & Culture Advocacy Program, I’ve always been interested in the work that they do.

In the two examples you gave—the feminist art in Iran and the art by imprisoned artists in Indonesia—in both cases, the language the institution used had to be changed to be a bit less provocative so as to not bring the government down on them. That's an interesting kind of balancing act. If you hadn’t adjusted the texts, the art wouldn’t have been seen at all, right?

Well, in those instances, those were the decisions of the local curators who were assessing the reality and the feasibility of how they could talk about their projects locally. And that is clearly, yes, a type of self-censorship, a strategy for survival or viability in those particular contexts, where they don't have freedom of speech in the same way to be critical of political policies. So, in those circumstances, I felt very proud to be supporting cultural projects like those that were sort of smuggling in certain ideas, in a way. Those are meaningful projects to support, for sure.

Those artists are pushing the discourse as far as humanly possible in their political context, despite very significant repression.

Definitely, and I think there are clear analogs here, as well. Artists that we've helped sometimes question whether they should continue doing the type of work they want to do, because that type of work is often met with resistance or repression once it becomes public. Whether to prioritize visibility and commercial success or to create the work that feels most true to them is a frequent question. I think a lot of artists face that, particularly if the themes or aesthetics around the work that they prefer to create are ones which some people don't like or that might be unpopular among particular groups.

Can you give an example of a particular artist who’s had those questions?

Yes, there's an interview on our website with an artist named Evan Apodaca, and in it, he talks about a project that he was invited to do at the San Diego Airport. It was a project that, in his original proposal, was going to be about the historical impact and influence of the US military in San Diego. The project is indeed about that, and it takes a critical view. It was supposed to be up, I think, for about five or six months, but it was taken down after only one month. His proposal had been reviewed by a panel among many other works that had been explicitly selected, and then it was prematurely taken down. The reason the airport said it was taking down the work was that the artwork didn't match the original proposal. Now, all of the visual elements were consistent. The narrative was consistent in terms of some of the voiceovers that he was using. It was just some of the nuance of the artist's position and the position of some of the subjects that he interviewed on the topic of the militarization in that particular city and its history. But at the end of our interview, he asks himself, what's the benefit if I do work like this and it doesn't get shown? Am I really succeeding in my role as an artist to share and to show? He says it much better in the interview, but that’s a sentiment that a lot of artists grapple with, particularly if they face overt censorship.

And what do you say to them?

I can't answer that for them. But, I mean, there are negotiations that every person makes in their lives in terms of how they present themselves or how they present the work that represents them. That’s really for the artist to answer. But when artists feel that they can't say what they need to say, that's when we want to support them. Or if they feel like they are suddenly being punished or censored for what they feel they need to say, we are here to advocate for their work to be shown. And we’re here to advocate for cultural institutions and curators, and all those who support cultural institutions, to have the courage to allow difficult conversations to happen.

Logan Royce Beitmen is a writer and curator.

Did you like what you read here? Please support our aim of providing diverse, independent, and in-depth coverage of arts, culture, and activism.