Novelist LYDIA KIESLING talks about class, power, politics, & desire

Photo by Erica J Mitchell

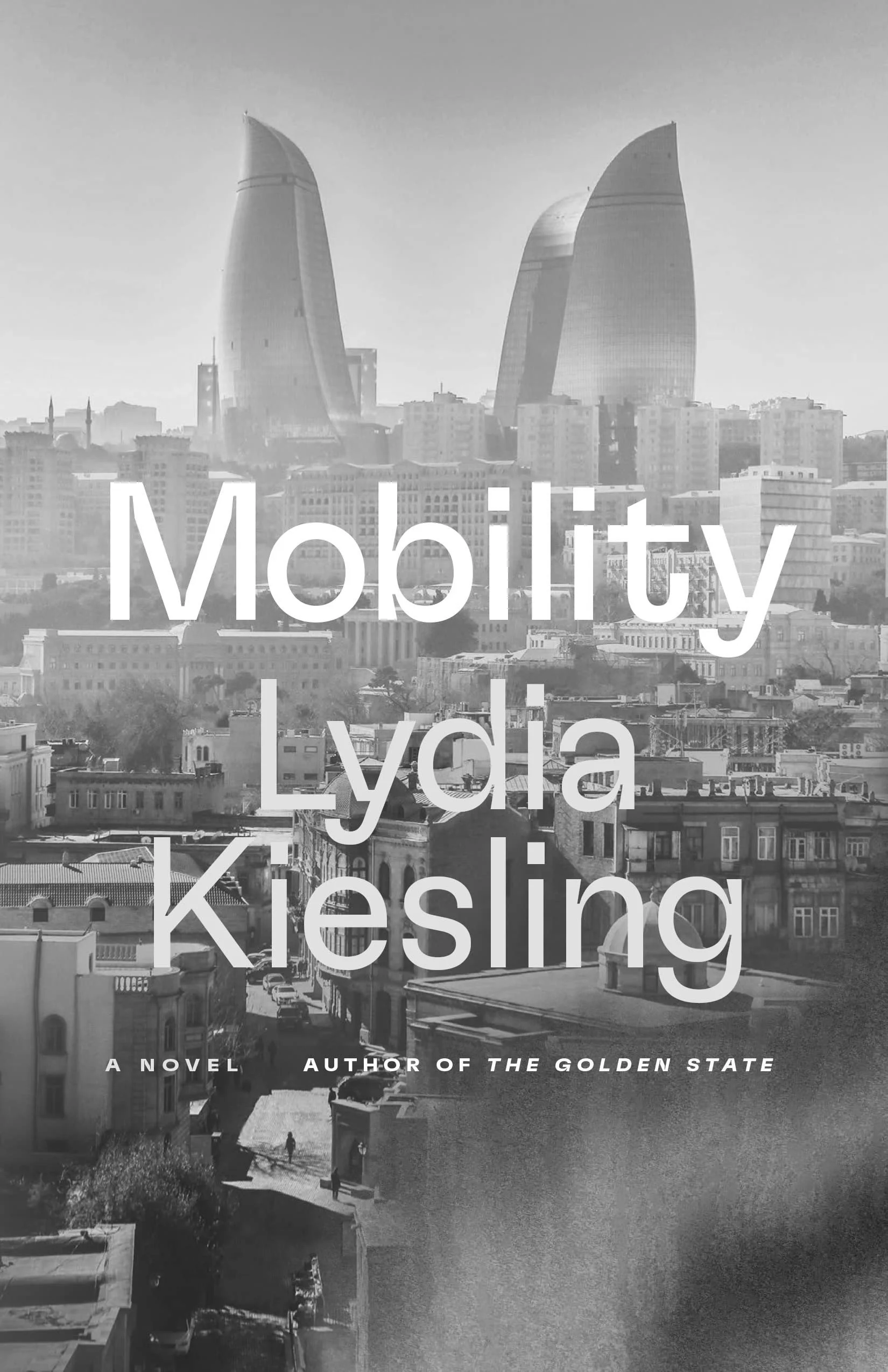

Lydia Kiesling is a novelist and culture writer. Her first novel, The Golden State, was a 2018 National Book Foundation “5 under 35” honoree and a finalist for the VCU Cabell First Novelist Award.

Her second novel, Mobility, a national bestseller, was named a best book of 2023 by Vulture, Time, and NPR, among others. It is a finalist for the Oregon Book Award. Her essays and nonfiction have been published in outlets including The New York Times Magazine, The New Yorker online, and The Cut.

Interview by Nirica Srinivasan

Your protagonist, Bunny, is a fascinating character—she’s largely uncurious, and often uncritical, of the world she lives in and the role she occupies within it. What was it like, on a craft level, to write a story from that limited, often self-absorbed perspective, especially as Bunny grows from a teenager to an adult?

It is very difficult! My first renderings of what became this book were much more sarcastic and overtly satirical, but it was exhausting to read them even in small pieces. The disdain (or perhaps more accurately, sublimated self-loathing) for basically all the characters was so foregrounded in those early efforts that it made the reading experience unpleasant. I had to step back and think about what made reading pleasurable—because I do believe reading novels should ultimately be a pleasurable and/or aesthetically satisfying experience.

I had to make more room for the characters, particularly for Bunny, to be a real person, which meant letting myself empathize with Bunny, and even sometimes love her, and let the critique be far more diffuse. I also had to tamp down the impulse to make glaringly obvious signposts whenever Bunny was doing something that I don’t agree with, so that I could allow the reader to draw their own conclusions. This has led, of course, to the pain of being wildly misread by some readers, but it has also led to a more interesting book, and it made me grow as a writer. The beauty of fiction is that, unlike an op-ed or essay, you don’t have to irrefutably prove some axiom or solve an intractable problem. You get to explore a topic more expansively through story.

Relatedly, how did you construct the world and the characters around her? How did you approach bringing in different perspectives and ideas through characters who had to take a secondary role in this story?

It was very important that Bunny’s myopia about certain topics not go unchallenged, either to herself or to the reader, and I needed strong secondary characters to present information and context and ideas that I wanted to raise in the novel. I thought a lot about the characters of Charlie, a journalist Bunny meets as a teenager, and Sofie, her brother’s girlfriend, both of whom have more much developed politics and different points of view.

But the worldview of the novel is still constrained, because those characters are themselves are limited in their ways. Charlie especially is a “problematic” character, or more accurately a flawed human like Bunny, because his rightness about some things does not obviate his wrongness about others, although I do hope he suggests, to discerning readers, how some kinds of wrongness are more easily excused in our society. And the viewpoints are constrained in that the novel does not engage with, for example, on-the-ground activists or many people in communities that are more directly impacted by fossil fuel extraction. It is fairly confined to relatively elite spaces. That was also a decision I had to make early—that this novel was going to stick to a particular world but describe the hell out of it, even if that would result in a perhaps regrettable insularity.

You did an enormous amount of research to write this book—not just nonfiction books about, among many other things, the oil industry and climate change, but also fiction and documentary reporting, as well as your own on-ground research. What was that process like? How did you decide on aspects of knowledge that had to be left out of the narrative because of the story's scope—to narrow it down to what would be relevant to Bunny’s perspective?

I did a lot of research in part because early in the process, when I only knew that I wanted to write a realist novel about a foreign service family, I started reading about the geopolitical context of the Caucasus, where I wanted the family to live (my dad was in the foreign service and lived in Armenia in 1997). The oil rush around the Caspian became really fascinating to me in what it revealed about the networks of global power, and in the way it connected to other things that were happening at the time, namely the American pivot from the Cold War to the so-called War on Terror.

I then became very caught up in oil as a narrative device, thinking about the truly endless stories that could be told about it, particularly as it intersects with momentous events in recent world history. I had this idea that I wanted to write some huge oil novel sprawling all over the world, maybe about one of the archetypal oil men. I did a lot of chaotic reading and flailing before I ended up back where I started, with Bunny and her family, and I resolved that I didn’t have the chops to write that big novel and instead needed to figure out a way to get oil into Bunny’s story. Sticking with her necessarily limited the material—the limit was set by the distance I could stretch a plausible career for her, or her self-taught oil education, or how much ancillary detail I could realistically provide through characters like Charlie and Sofie or Bunny’s bosses, which meant leaving lots of things out. I’m haunted by things that didn’t go in! But I hope so many more people write oil novels. It is a really interesting and worthwhile narrative challenge, and so thorny ethically too.

Mobility has a wonderful sense of balance between difficult perspectives and ideas, and it’s sharp and often very ironic. How do you walk the line between being didactic and informative—and humorous!—in your writing?

At first it’s just about trying to stuff as much as you can into a scene or a conversation, and then it’s about reading and rereading to make that dialogue sound natural and real, or at least what I’ve coded as natural and real but maybe is really more cinematic (I can feel the influence, in some of the characters, of watching a lot of TV in my spare time). Real people are often a lot more boring and repetitious when they speak. I also had to create characters who could support an expository role and basically give good dialogue—Charlie is a lone ranter who fixates on an idea and uses a lot of very sarcastic humor, and Sofie is more of a conversational proselytizer with a (feminized) organizing instinct.

I think the balance comes back to something touched on in the first question, which is constructing a narrative that is pleasurable for the reader. People like to laugh, and they like antiheroes doing embarrassing things, and they like workplace bullshit, because most people have done something embarrassing or have dealt with workplace bullshit or felt out of place in a given environment. In some ways the book is a betrayal to readers, because it does sort of lure the reader in with humor and possibly some identification with the protagonist, and then punishes them for it at the end.

Much of your book is about story-spinning and public relations efforts that rehabilitate or reframe industries, actions, or ideas. Bunny reminds us also of how those stories impact how we narrate ourselves to ourselves. I’d love to hear more of what you think about that.

When I was trying to create a narrative about oil that I myself could understand, since it is such a sprawling and complex topic, I found with some alarm that I started to do that storytelling to myself—first you get a sense for the vast scale and importance of the industry, and then that leads to a little bit of horrified awe, and then it leads to some grudging respect to the effort that goes in, and a lot of respect for (some of) the workers who have powered the industry, and then before long you’re rhapsodizing about the standard of living this kind of development allows (some) people to enjoy.

I could feel how easy it is to come up with those stories to justify a lot of things, and justify the inevitability of fossil fuels, because I was essentially creating them for myself without conscious prompting. Realizing that helped me understand how the oil industry capitalizes on that tendency and seeds those sentiments wherever it can. And that felt like a productive irony to me, because storytelling is considered more of a feminized skill, and part of Bunny’s sense of worthlessness when she graduates college comes from the fact that she was an English major and read books and found herself with nothing of value when she entered the labor market. But stories and narrative have been so critical to the survival of the fossil fuel industry, especially in these last few decades when it became more widely known that they were cooking the planet.

Your book moves across decades, from 1998 to 2022. The last chapter, however, moves far forward into 2051. In some ways, the world we see in this imagined future seems inevitable, given everything we’ve read till then. Why did you decide to end your book in the future, and how did you approach creating that brief but powerful vision of 2051?

I really resisted having anything set in the future, because I didn’t want the novel to feel preachy and that felt like it would be a big billboard screaming “everything we are doing is bad.” It’s maybe a braver book to not include that and simply serenely do the work of describing a way of living and a course of action that is going to result in disaster.

But ultimately, I felt like I needed to acknowledge that future for myself, by laying it out in broad strokes, to somehow clear the air in the book and make some things very evident (although the ending is maybe too sanguine). I also wanted to show how class affects the experience of climate disaster. In Portland, Oregon, where I live, we had a thousand-year heat wave with 116-degree temperatures and the people who died were people who were poor.

One thing that is remarkable about living today is that we have evidence everywhere that the situation is becoming untenable—thousand-year floods throughout the year, thousands of people dying in single catastrophes—but by and large people outside the areas immediately affected by these catastrophes—and people temporarily insulated by their class—continue to go about their business. We live now with so much information and so much visual confirmation of things that are happening. But it doesn’t seem to do anything apart from heighten the frog-boiling-in-the-pot sensation. I wanted to show someone who is getting closer and closer to boiling and still doesn’t realize she is both the frog, and the chef. Not the only chef in any sense. But she played her little role.

I loved how you used specific cultural moments to mark the time passing in your novel—Bunny goes to see Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy in cinemas in 2011 and watches Mission: Impossible—Ghost Protocol shortly after its release; she downloads Bumble in 2014 (the year it launched). What was that process like to paint a picture of what the world—Bunny’s world—looked like through the years?

So much of the subterranean, non-didactic work of this book—so maybe its truest project—was a kind of nostalgic excavation of the objects and cultural references that embed in the mind throughout life. That part was fun to do—it started with the signifiers of a certain kind of teenage girlhood in the late nineties, which are seared into my memory, and then with the aughts and teens it was sort of picking from a grab bag of jumbled references.

Once Bunny got older the references became a bit more studied and calculated, because she and I started to diverge more, not necessarily with the mainstream pop culture stuff like movies, but with things like shoes and clothes (I love nice clothes but my life is such that I wear stained pants and a Pigpen sweatshirt that says “no showers no masters” every day—different from Elizabeth/Bunny when she is my age).

Your book was the first book published in Zando’s imprint Crooked Media Reads, which is an interesting experiment in book publishing in the context of politics and fiction or art in general. What did you think about this experiment? How do you think it’s impacted the way Mobility has been received?

I ended up at Zando because my editor for Golden State, Emily Bell, had gone there from my previous publisher, FSG/MCD. I followed her, and she and Zando made a compelling case that their Crooked Media partnership/imprint would expand the audience and reach of what is fundamentally a slightly meandering work of literary fiction, which otherwise might have a quieter reception.

I trust Emily, and Crooked seemed to be trying a lot of things—they had just brought a climate podcast I really respect under their umbrella, Hot Take—and so I took the chance, knowing from my preexisting relationship with Emily that I would have editorial and creative freedom.

Trying something new is always a gamble, especially in media. (The climate podcast I admired was summarily canceled, for example, which upset me.) In terms of audience, I think some people who consider themselves Politics People read the book who wouldn’t have otherwise, and some of them really liked it. Then again, some of them (I’m hazarding a guess based on my Goodreads reviews) either do not have an ability to recognize subtext or don’t think that there is a political valence to the lives of women, even or especially women they don’t like, so they complain that the book isn’t political or interesting, because it’s not political or interesting in a way they notice.

And of course, I worry about who might not read…people with radical politics who I admire might dismiss the book because of its association with a mainstream political brand, or maybe people who are serious about literary fiction dismiss it because they think I’m being published by a podcast. But those are neurotic writer thoughts about things that you never have any control over anyway. I have gotten wonderful support from the publisher, and the novel has gotten great coverage and reviews that treated it as a serious work of fiction that was trying to do something interesting. And that means everything.

Read more of our book reviews and author interviews

Nirica Srinivasan is a writer and illustrator from India. She likes stories with ambiguous endings and unreliable narrators.