MARY JO BANG isn't lost in translation

Photo by Carly Ann Faye

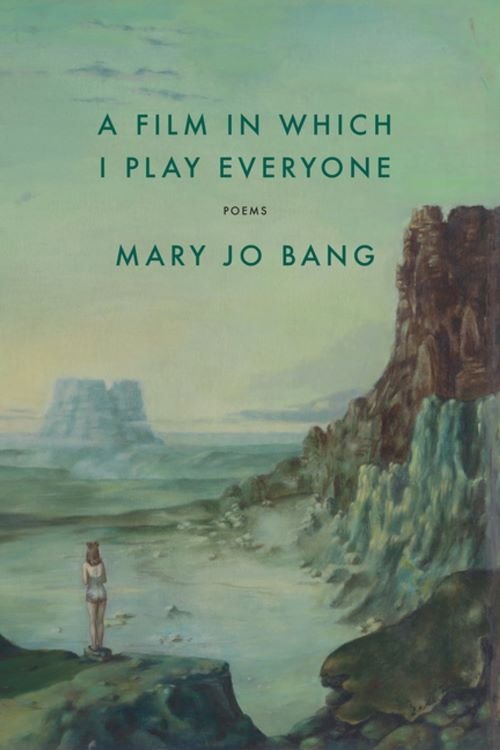

Mary Jo Bang is the author of nine poetry books, most recently A Film in Which I Play Everyone (2023), published by Graywolf Press. She has also published translations of Dante’s Inferno and Purgatorio and Colonies of Paradise by German poet Matthias Göritz.

She received the National Book Critics Circle Award for her book Elegy, and has also earned a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Hodder Fellowship, and a Berlin Prize Fellowship, among other honors. She teaches creative writing at Washington University in St. Louis.

Interview by Isabelle Sakelaris

Who and what are your influences and inspirations? What were you reading, watching, or listening to, or doing when you wrote these poems?

One thing that was happening while I wrote these poems was the pandemic! I was also working on a translation of Dante’s Purgatorio. The sense of trudging up a mountain so steep one can’t see the top felt similar to the pandemic. The insistent reiterative question in both cases was, will it never end?! My friend Timothy Donnelly would send me CDs from time to time, and I would listen to those on automatic repeat: Cowboy Junkies, “The Trinity Session,” Beach House, “Once Twice Melody.”

I moved my laptop from my study, which is in the east-facing back of the apartment, to the living room, which has a bay window through which I could at least watch the sun go down each day and the weather change. Because I was working steadily on the translation and rarely leaving my apartment, the days lost their edges. The bright moments were those that announced a difference, fewer sirens headed for the hospital down the block, for instance. I would make note of those moments in poems. I always live inside my head but during that period, I was probably even more focused on my own interiority. Thoughts would become scenes, which I would people with actors who looked like me and those I knew.

Does your work in translation inform your poetry? Does your poetry inform your translation? What energizes or interests you about the two disciplines?

I didn’t realize it in the beginning—and by “the beginning,” I mean twenty years ago when I first began translating Inferno—but yes, I now see that translation has informed my poetry. It has made me more sensitive to the way language works. And Dante, in particular, taught me that you don’t need to overwork the rhetorical surface in order to express complicated ideas. I had often used indeterminacy in an effort to not be reductive, but I came to understand that there are many ways to avoid being reductive, and one of them is through an invented narrative, which can often get closer to the truth than natural or commonsense realism does.

You wrote a very interesting essay on Beatrice, Dante’s beloved, and why it takes so long to meet her in Purgatorio. You noted that Dante held her in higher esteem than was typical for women figures in that period. You posit that, as a result, she was a less influential figure to other artists—mostly men—than Francesca, who exemplified the “damsel in distress” trope.

What was it like to translate such old and revered works like Dante’s, especially as a woman? Did you face any pushback on your interpretation of the text? Conversely, did you feel your identity and experience helped illuminate parts of the text that have largely been ignored or glossed over?

I should first say that an editor replaced my original title, “Oh to Be Beatrice,” with “Mary Jo Bang Wonders Why It Takes So Long to Meet Beatrice in Dante’s Inferno.” The fact is Dante never meets Beatrice in Inferno. Only Virgil meets her in Inferno and it doesn't take long at all, it occurs in Canto II. And Mary Jo Bang has always understood that Dante has to go through all nine circles of Hell and then climb the whole of Mount Purgatory before he can meet Beatrice and that his desire to finally be reunited with her is what motivates him over the course of his long and exhausting journey!

In terms of the question of what it was like to translate Dante, I admit it was intimidating. I knew I could never imagine what it was to be a man from the medieval era, or a Catholic, or a political exile. There was, however, one identity that Dante Alighieri and I share and that is “poet.” It was that distinction I kept falling back on whenever I had doubts. I’d ask myself, “What would I do as a poet?” and that knowledge would shine a light on whatever tangled skein of language I was trying to see through.

Like the character Dante, I also know something about being “lost in a dark forest.” That knowledge is timeless and independent of sex or gender. It’s true, I have from time to time experienced “pushback” on my approach to translating the poem into the contemporary vernacular, but what is most interesting to me is that that resistance has most frequently come from people who are not translators. I’ve been very honored by the attention the translation has been given by Dantists, and have been reassured by them that what I’m doing has value.

The second poem in part one of A Film in Which I Play Everyone, “Here We All Are with Daphne,” alludes to Daphne, a dryad from Ancient Greek mythology who was turned into a tree by her father as she fled the god Apollo’s advances. Historically, many poets have used ancient mythology to great effect (for example, Keats’s ekphrastic poem “Ode to a Grecian Urn”). What applications does ancient mythology have in contemporary poetry? Do you think it serves the same purpose today as it did during Keats’s lifetime? Why or why not?

The problem with using Greco-Roman myth in poems is that most of us are not taught those myths in school. My own education in myth has largely come from translating Dante. When I learned about the myth of Daphne, it resonated with my own experience. Daphne is committed to a life of independence. Apollo is often described as “overly amorous” or “infatuated,” but the fact is, in contemporary terms, he’s a stalker who refuses to take no for an answer and intends to rape Daphne if he catches her! She calls out to her father, or to Zeus in some versions, for help and is turned into a laurel tree.

In my mind, that’s not quite the rescue I imagine Daphne was hoping for—to be enshrined in what some man thinks of as her rigidity! I hope there is enough in the poem that regardless of whether the reader is familiar with the myth or not, they will sense that Daphne is a woman who has been silenced and will empathically relate to that state.

There are quite a few references to neuroscience and psychology in these poems, which seem tied to a theme of self-perception and understanding. At the same time, you write about how “the actual occurrences,” to quote the poem of the same name, “were responsible for defining who I was at any given moment” (89).

What do you think are the largest constraints women face in reconciling their self-perception with their socially constructed or historicized selves? Do you think social scripts or roles can be generative to a person’s sense of self? Or are they always a constraint in a society that favors some (for example, cisgender men) over others?

The “actual occurrences” are historical markers, both personal and societal. They form the background against which any life plays out. How an individual deals with those events is multifactorial. There is the brain’s hardwiring, which is largely genetic but is also the result of childhood nutrition and environmental factors. There is the class into which one is born. There is how much melanin is produced in the melanocytes in one’s epidermis, and how society views the resulting skin tones. There are hormones and the effect of those on personality and on the body. There are cultural scripts. There is luck, or the lack of it. And then there is institutional power and the self-interest of those who wield that power. Psychology and neuroscience can only go so far in understanding the effect of any one of these things. The complexity of all of these elements, and their intersectionality, make it impossible to generalize about the problems that women face: Which women? Born where? And when? And in which class? And with what skin tone?

In the “Notes”* section of A Film, you mention that the collection's title came from David Bowie's response to a fan who asked him whether he would be acting in any upcoming films. Bowie said he was working on an “unauthorized autobiography.” Do you think the speaker(s) of these poems would consider this book an “unauthorized (auto)biography?” Would you? Why or why not?

To the extent that any of the poems in A Film in Which I Play Everyone are autobiographical, they are surely authorized by me, the poet. But you may be asking whether all of the various people represented in the poems would authorize their appearances! The fact is, there are no “real” people in the poems. Each person is a composite based on those I’ve met in life, or in literature, or in my imagination.

In the poem, “The Starting Point,” for example: a couple appears to have kept their shared money in a tin. I never did that, but back in the 70’s, I knew two roommates who did. A man in that poem is miming playing a piano on the tabletop. When I was in high school, a student in my English class did that on his desk. I did once read a translation of Le Rouge et Le Noir (The Red and the Black), an 18th-century novel by Stendhal, but not while breaking up with someone!

I’ve written a scene where, hopefully, the speaker’s sense of powerlessness reveals itself, the way that powerlessness will reveal itself at certain moments in one’s life. I drew on feelings I have had, and I constructed a moment around those feelings, using selected details to create a sense of verisimilitude. What is important to me are the feelings—those are mine but not uniquely mine. I want the poem to be a mirror in which others might recognize not just me, Mary Jo Bang, but themselves as well.

*These lines are in “Green Earth”—

“Bowie saying, I’ll finance the film version / in which I’ll play everybody”—but the explanation of the title is found in the Notes section:

From the Notes section—

“The book’s title, A Film in Which I Play Everyone, was inspired by a quote by David Bowie, “I’m looking for backing for an unauthorized auto-biography that I am writing. Hopefully, this will sell in such huge numbers that I will be able to sue myself for an extraordinary amount of money and finance the film version in which I will play everybody”; this was Bowie’s response to a fan question from someone identified as Angst, who asked “Any movie roles in the near future?” “David Bowie 50th Birthday Live Chat Transcription on AOL—8/1/97.”

Check out all of our in-depth interviews with writers.

Isabelle Sakelaris is an art writer and aspiring poet who lives and works in New York City.