IT AIN'T ME BABE: Richard Prince's endless empty appropriations at Gagosian

Richard Prince, Folk Songs, 2025, installation view. © Richard Prince. Photo: Maris Hutchinson. Courtesy Gagosian.

Have you heard the cliche about white people not having any culture? If true, it’s best exemplified by the American artist Richard Prince. There’s a mobility to the dizzying array of personae he adopts which, it occurs, is only possible if you don’t have a central, personal one to go back home to, yourself.

This undecidability is one of few common threads in the artist’s chaotic oeuvre. Prince is constantly assuming new identities, whether swiping your Instagram selfies, collaborating with Colin de Land as the fictional artist John Dogg, publishing an edition of The Catcher in the Rye indistinguishable from the original except for replacing the author’s name on the cover with his own, or (as has been speculated), producing paintings shown by Prince’s gallery attributed to Bob Dylan. The most then-current body of work at his 2007 Guggenheim retrospective Spiritual America was referred to as his “de Kooning”s, but let’s stop right there: the man is no de Kooning. That’s the joke. That schlock-y neo-primitive work developed into the Basquiat-ish knock-off figures that appear on his cover art for A Tribe Called Quest’s triumphant reunion album We Got It From Here… Thank You 4 Your Service. The group had to have been cognizant of arguments about European abstract painters like de Kooning and Picasso stealing from African art wholesale when they tapped Prince for his treatment.

At first, Prince’s current Gagosian show, Folk Songs, comes as a curveball before you realize Prince has no substantial person in himself to produce art about or from, and once you do, the shock wears off. This is just his new wardrobe. He’ll have others. He keeps having others. And this particular multimillionaire is not “folk”.

Richard Prince, Untitled (Folk Songs), 2023. Inkjet, collage, gel medium, oil stick, and acrylic on canvas. 72 x 72 inches (182.9 x 182.9 cm). © Richard Prince. Photo: Jena Cumbo Photography. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian

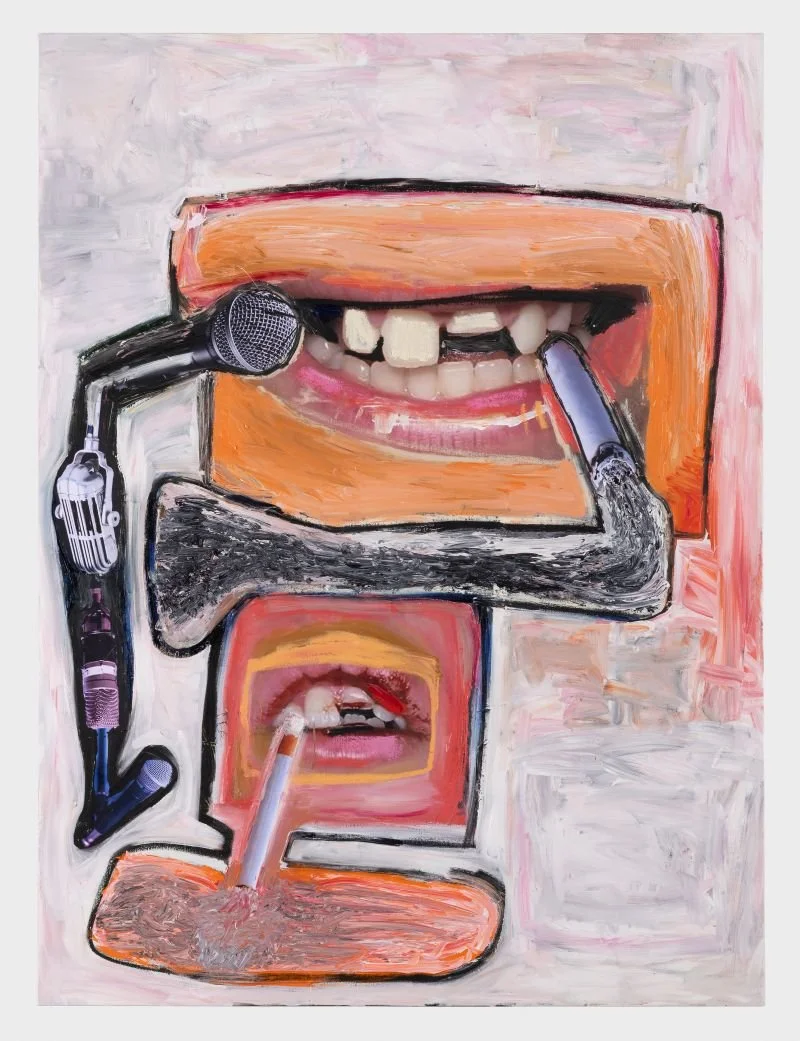

Folk Songs is image-hungry. It hoovers them up with reckless abandon in galleries lined with bricolaged canvases, all titled Untitled (Folk Songs). A slurry of microphones meets a barrage of missing tooth close ups, cigarettes, and shots of horrific stitched up wounds. It’s exceedingly teenage. Some have diagrammatic drawings of stereotypical hexagonal coffins. There are pictures of many of the sculptures also on view woven into the mess. Energetically slathered paint strokes that coat the edges of the printed collage elements turn them into funny exquisite corpse tableaux extending their parts into silly shapes.

The concluding lines of the exhibition’s glib, sparse press release suggests Prince wants us to think of Philip Guston’s grubby pink smoking figures with his palette and the cigs. “All these doors connect because I locked myself in and I locked myself out.” This is reminiscent of a famous, possibly apocryphal story told to Guston by John Cage concerning baggage artists must clear their minds of: “When you start working, everybody is in your studio—the past, your friends, enemies, the art world, and above all, your own ideas—all are there. But as you continue painting, they start leaving, one by one, and you are left completely alone. Then, if you’re lucky, even you leave.” It goes without saying Prince is no Guston or Cage, either.

Richard Prince, Untitled (Folk Songs), 2022. Acrylic, inkjet, and collage on canvas. 59 x 44 inches (149.7 x 111.8 cm). © Richard Prince. Photo: Jena Cumbo Photography. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian

The integration of the found images collaged into new configurations is more worked on than in the infamous Canal Zone paintings from 2008, in which documentary photographs from a photo book by Patrick Cariou of Rasta culture were limply arrayed to convey something about a sci-fi script. More comprehensible information is available about the trial between Prince and Cariou over the use of these images than the premise of their use.

This reviewer, like many art enthusiasts, delighted in the recent release of a 6-hour Prince deposition from 2018 taken while being sued by Donald Graham and Eric McNatt in connection with his Instagram screenshot pieces (Deposition, 2025). We put it on in the background of our apartments and studios like some novel fusion of legal podcast and guided meditation. He employs Michael Moore’s Roger & Me device of playing the simple, cantankerous everyman while lawyers in suits grill him on his every aesthetic decision. It’s the longest and most affirming pornography I’ve ever watched. Prince grumbles, rambles, and waxes sublime. We ate that up, but I’ve been eating that slop since 2011 when indefatigable artist, archivist, and critic Greg Allen did the work of printing the entirety of Prince’s previous deposition in the case of Cariou v Prince. I read it religiously after work at my factory job in Philadelphia, drawing amused reactions from the yinzers at the bar.

Prince, the public-facing artist, is distinct from the guy who owns a town-sized upstate compound and presumably has an army of assistants. The former sits and says plaintive—yet conveniently evasive—things about his work in front of lawyers in suits. The latter guy is responsible for this show and has his hand up the ass of the former like Jim Henson manipulating Kermit the Frog.

At the age I was when I was breathing dust on the factory floor, Prince was himself working at Time Inc., supervising image archives for magazines, and it’s hard not to understand that as instructive for the remainder of his career. Identities, like his Marlboro Cowboys or Biker Girlfriends, were simply images circulated. Nothing behind the dead, empty-eyed facades. Just images. No history. And they’re fungible images, replaceable on a whim to serve whatever need. Nothing built, only surfing. Gliding along slick corridors of pictures made all the smoother by the advent of Google image search. It’s what Chat GPT would excrete if you input the correct terms for safely provocative painting. Things are connected together. Images are mashed into obedient submission. Derived from where? Who cares?

Richard Prince, Folk Songs, 2025, installation view. © Richard Prince. Photo: Maris Hutchinson. Courtesy Gagosian.

It’s hard to articulate, because the pleasures of outsider or folk arts are often ineffably strange and unpredictably specific, but his sculptures gesture towards making good on Folk Songs’s show title. There’s an ad hoc ingenuity to them that is on its face charming in the way folk arts are. Canvas stretched over an old ladder and outboard motors on a beefy, well-used saw horse. But what makes folk arts interesting are folkways, the progression of traditions carried on in specific groups of people evolving generation-by-generation outside a mainstream marketplace. Folkways are, at heart, making things work as best as you understand them, day in and day out, because you have to, but also finding something unique of yourself in them in the process, and perhaps diverging from the norm. What results answers a function differently than what us insiders to the humdrum capitalist machine expect, which novelty is a large part of their appeal. But what is Richard’s story? What folkway delivered the bundle of cardboard tubes? Where did they come from? This is not sui generis genius. It’s a knowing fraud he saw somewhere else and has denuded of its history like so many other images he likes to gargle and spit in our faces.

Judith Scott, to provide a counter example, was absorbed in process rather than attentive to its outward appearances. The deaf artist who lived with Down Syndrome is known for obsessively bundling materials, which I have always thought were the most human of impulses to follow. Do I even need to say that wrapping stuff is good work that unites us as we head into the holiday season? Scott wasn’t playing a Warholian game of personality, but even she becomes a product in the world of gallery representation and sales as capital’s gravity exerts its pull. Gee’s Bend quilts from Alabama likewise fetch heftier sums these days than their earliest generation of progenitors saw, and provide a healthy support system for their present-day practitioners, but they weren’t initially made with that in mind. They were first meant to keep you warm. Again: bundling is good.

Richard Prince, Folk Songs, 2025, installation view. © Richard Prince. Photo: Maris Hutchinson. Courtesy Gagosian.

In wrapping up, I recall a week in 2016 with two friends, each brilliant painters; one a canny Texan punk shit-kicker, the other a lush art historical traditionalist that exists infrequently enough to be, herself, Punk As Fuck. They were hosting me in Virginia in the months before Donald Trump was elected the first time and in the years before their first child was born. Together we perused the tiny shack and creations of their neighbor living alone very much off the grid. All manner of things were stapled together in baroquely inventive ways. Doll heads and broken china. Sticks and stones. It’s the kind of thing you wish you had a photo on your phone of to call up, but which is immediately profaned by photography. It exists for itself and is a whole world unto itself. It is a world Richard Prince—at his best—can only apologize to you for lacking. It is the carefully cultivated, sacred culture a white person could lay legitimate claim to, and find private delight in, but it is not Richard Prince’s culture, pretend as he might. His apology is simply lurid clothes on a limp provocation to one’s bourgeois sensibilities. Quoth the pallid emperor’s new threads, taking a line from Bob Dylan: “I’m not there.” The emperor barely is, himself. We’re looking at air.

Folk Songs is on display through December 20, 2025, at Gagosian Gallery, 555 West 24th Street, New York

Joshua Caleb Weibley is a writer based in Brooklyn, NY. He also acts as executor of the estate of Joshua Caleb Weibley, which has staged exhibitions at various venues in America, including Game Transfer Phenomena at CHART gallery early this year.

Did you like what you read here? Please support our aim of providing diverse, independent, and in-depth coverage of arts, culture, and activism.