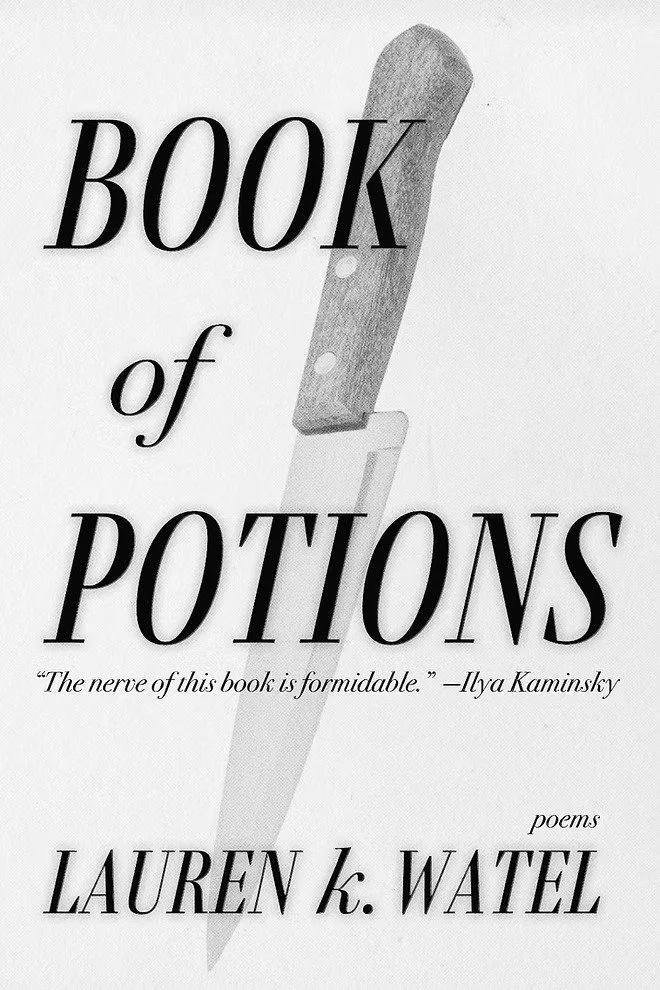

The sharp precisions in BOOK OF POTIONS

Photo by Ashley Kauschinger

Lauren K. Watel is a poet, fiction writer, essayist, and translator. Book of Potions, winner of the Kathryn A. Morton Prize in Poetry from Sarabande Books, is her first book. Her work has appeared widely in journals such as The Paris Review, The New York Review of Books, and The Nation.

Her work has also won awards from Poets & Writers, Writer’s Digest, Moment Magazine-Karma Foundation, and Mississippi Review. Her prose poem honoring Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was set to music by Pulitzer-winning composer Ellen Taaffe Zwilich, and the piece premiered at the Dallas Symphony. Born and raised in Dallas, Texas, she lives in Decatur, Georgia.

Interview by Nirica Srinivasan

The first thing that stuck out to me in Book of Potions is how apt the cover image is—every piece in the book felt as sharp and precise as a knife, no words or actions wasted. What does the image of that knife mean to you? How did you chisel these pieces down to this sharpness?

Danika Isdahl, a wonderful book designer, thought of the knife—it didn’t occur to me—based on one particular potion, “Give the Child a Knife.” It’s a brilliant cover image, elegant and simple. The knife as an object carries so many resonances, from its utility to its threat of violence. And knife language is so evocative: sharp, pointed, edgy, piercing, honed, slice and dice, stab, cut, gut, and on and on.

In terms of the book as a whole, I think the knife works on many levels. For one thing, it embodies, in a very concrete way, the anger I was feeling when I wrote many of these pieces, my desire to lash out, to cut or wound or slash. I was feeling disempowered, bitter, depressed, and when you feel that way, you often long to do damage, in desperation and rage, and the knife carries this feeling of potential destruction.

But the knife also reminds me of my obsessive tendencies to probe my interior, as if I were a surgeon of my own emotional life. I’m constantly turning the knife on myself, cutting myself open, to slice through the surface and see what I’m made of, to find out what’s happening in there.

Once I get some of that interior gook out in the open, onto the page, I start going at it with the scalpel. In other words, editing the pieces, and that’s a trick, to cut anything unnecessary but leave in what was most crucial, without diluting their weirdness and wildness.

Sarabande Books

The word “potions” is so effective—so succinct, and evoking such strong associations. How did you come to realize that you needed to invent this new form for this collection, a mix between poetry and fiction? And how did you work on that across the length of an entire book? I was struck by how the potions felt at times universal and fable-like, and at other times so specific (as if finding a signpost in a dream!).

Everything about this book happened in reverse of how you might imagine. At a time of great personal turmoil, I started scribbling one page every morning in a notebook, mainly as a form of warm-up writing. I didn’t read what I’d written, much less consider it part of a collection. It wasn’t until years later, when I discovered that notebook in a drawer, that I thought this material might amount to something.

However, I didn’t know what that was. The pieces were unlike my other writing, very unhinged and, in a certain way, exposed. Many things about this scared me; I wasn’t even sure they were good, but I knew they were compelling. Despite my fears, I persisted, typing them out and even writing new pieces in the same manner, quickly and unthinkingly.

So I didn’t start with the intention to write a book, nor to invent a form; in fact, I’d say the form invented itself in the writing. Out of necessity, it seems, to contain the chaos of my inner life. I thought up this portmanteau—"potion,” a cross between poem and fiction—while on a run, a tasty bit of cleverness I couldn’t believe no one had thought of before, but this was long after the pieces were written.

The different tenors of the potions, encompassing both the universal and the specific, as you point out—this was also completely unintentional. I suppose it must reflect my many attempts to articulate in language, morning after morning, whatever was reeling and roiling inside me, to express it in various fables, scenes, portraits, and dialogues.

I love the “book club questions” you’ve prepared for Book of Potions—they’re such a perfect companion to a book that can feel surreal and offbeat, funny and unsettling. I feel like many of the potions also pose questions that are left unanswered, or that answer themselves in a way—questions like, “Where is everyone?” or “what would I do for eyes with my head in the clouds?” or “Do you trust me? Do I trust you?” What draws you to questions? What is the importance of an unanswerable question, or one where the point itself is just that the question has been asked?

Oh, thank you, I had fun writing those questions, which were very much in the spirit of the potions. Questions are at the heart of our existence, aren’t they? Like all organisms, we as a species have to survive in an ever-changing world. Uncertainty, not-knowing, is the norm. Unlike most other organisms, however, humans evolved to be self-aware; therefore, we are by nature creatures who question. To make sense of the world and ourselves, to deal with uncertainty, we ask: Why are we born? Why do we die? Does life have meaning? Why does suffering exist? Why joy? Who are we? Who are they?

These just for starters, all questions without definitive answers, but crucial questions, and probably universal. Asking, and trying to answer, is how we came to have mythologies and religions and science and poetry, right? But the questions proliferate, and the answers elude us. It’s like trying to catch your shadow, all this asking.

I ask questions out of curiosity, out of fear, out of desire, out of anguish and despair, out of loss. Even so, I believe that questions, even if unanswerable, can be a form of hope. As long as I keep asking, keep trying to know, even if knowing is out of the question, I’m still in the swing of life. The bigger questions are often a grasping for the unknown, toward the beyond, the ineffable, that which passeth understanding. In this way questions are also like prayers, uttered into the perhaps-unlistening void.

The questions in the potions, they told me so much about my state of mind. That I was feeling unmoored, anxious, that I was searching for answers. It’s always been scary to be alive, but perhaps now it’s even scarier. So, of course, we ask: What’s happening? Why is everyone doing drugs or selling them? What is a father, exactly? Who could have done this to you? Was it someone you knew or a stranger? Why should we fight? Why do we have enemies? What am I afraid of? What did you do wrong? Is it a taunt? An invitation? Why now? Why today? (All from Book of Potions.)

What do dreams mean to you—what importance do you place in your own dreamscapes?

Unfortunately, I forget almost every dream as soon as I wake up. And if I remember a dream, it’s gone before breakfast. As a result, I don’t have much access to my own dreamscapes in the form of dreams. But I do love dreams, and I find other people’s dreams fascinating. I like to approach any dream as a text of sorts, which I try to interpret, in a vaguely lay-Freudian way.

Writing the potions, which I often did first thing in the morning, gave me access to the workings of my unconscious. The unconscious seems to operate much the same as dreams do, by associations, substitutions, metaphor, leaps in time and space. The dreamscapes in the potions ended up exposing the turmoil under the surface of my awareness. They showed me my own feeling. But slantwise, the way dreams do.

For example, I wasn’t saying, Getting old is unpleasant and alarming and erasing. I was saying, My hair, my skin, a map of experiments. Or, When it hits you that your face is missing, peeled back from your skull-front like a lavish window display lifted from a fancy shop, you can do nothing; it’s already long gone. Or, I’m still asleep, wrinkled across the sheets, legs crossed, skin drooping, hair all agray. Blind, stupid, flabby and useless. (Also from Book of Potions.)

The potions, with their dreamlike il/logic, ultimately try to articulate, to make visible, a complex of emotions. Which are invisible, and therefore mysterious to us. These dreamscapes, like the questions they ask, become another form of grasping for the unknown. They are my attempt to reckon with myself, one tiny, helpless creature trying to survive, and even thrive, in a chaotic and hostile and dying world.

In the introduction to your book, Ilya Kaminsky says it has a “peculiarly American metaphysics of the self.” I'm intrigued by that. There are some poems that ground themselves in America and American politics, but with that fable-like universalness we've mentioned. What do you think of that phrase, “American metaphysics”? What does it mean to you?

Honestly, I’m not certain I understand it, as I don’t have much of a philosophical bent. If, broadly speaking, we decide that “American metaphysics” could mean something like “the nature of being an American,” I suppose I could take a stab at it. We’re taught that individualism is one of the great hallmarks of Americanness, and we value individual freedoms. There is something wonderful and admirable, very American, about upholding the dignity of the individual and an accompanying idea of radical liberty, free from undue interference by overpowerful institutions.

However, like any value taken to the extreme, individualism has morphed into a cult, with no nuance, and no counterbalancing checks. The blind worship of individual freedom has warped our notion of what it means to be a responsible citizen, and we’ve lost our sense of a collective that would supersede the individual or provide oversight and accountability. As we decimate regulations and let practically anyone carry a lethal weapon, we preference the individual over the collective, to our detriment.

Without substantial oversight, humans are not well-suited to self-management, either on an individual or a societal level. We are, most of us, exceedingly and unthinkingly immature, and though we believe we’re in charge of ourselves, our decisions are making us, rather than the other way around. So the idea that our system of government is increasingly leaving us to our own devices is scary and dangerous.

We’re facing the failures of the American worship of the individual, just as the individual is ever more in ascendance. Like many, I feel at sea, bereft, bewildered, panicked in my own country. I hardly recognize it. And yet, I’m American to my core. Perhaps the book is my way of grappling with these contradictions, of a self faced with its own powerlessness, even as it’s expected to be all powerful.

There are recurring motifs in this book, but one I was very drawn to is a kind of dissolving of boundaries—faces missing or limbs removed, the questioning of the difference between a man and his enemy. Were these also things that came to you sort of accidentally in the process of your writing? What were your favourite motifs that emerged across the book?

Yes, the dissolving of boundaries as a theme emerged organically. I’m sure this was because in the most basic sense I have not had good boundaries, nor a solid understanding of myself. From early in childhood, I had difficulty knowing who I was or what I wanted outside of what other people, especially my mother, wanted me to be.

I was rewarded for conforming and punished for not meeting expectations. And often who I was, my natural impulses and desires, were not what other people wanted for me or expected of me. So I ended up internalizing the idea that if I acted like myself, if I were myself, I wouldn’t be loved, and I wouldn’t exist. I felt that being entirely myself was bad, and a betrayal of those who loved me best.

All this is to say that my understanding of where I ended and other people began was confused, and I didn’t quite feel like a distinct person, with my own notions of myself. I believe this feeling, which tormented me, became literalized in these pieces. I was clearly drawn to vanishings, blurrings, dissolvings, because this is the way I felt, inside myself.

Also, even before the first term of our current president, I felt plagued by the sense that, because of climate change, species were disappearing. Further, that the earth as we know it is disappearing, and all we can do is look on, and hope against hope someone will do something, all the while sensing that it’s almost certainly too late. So this more global feeling of vanishing crept into the pieces as well.

Also, there’s an inevitable generational shift that happens as you plunge deeper into the middle of life, as I am: you see that you are aging out of the world, the constant march of progress leaving you in the dust, that all the latest innovations and cultural markers and slang are at the very least unfamiliar, at worst utterly alienating, and though you still have possibly decades left on the planet, your own existence has become a sort of slow-motion disappearance into decrepitude and irrelevance.

My favorite motifs? Rage, for one. The book is engined by a lot of anger, for many reasons. I love nothing more than a good righteous rant, as my people will attest. Vengeance is another. There’s a part of my personality that’s childishly vengeful. Sometimes I’m appalled and scandalized at the violence of my fantasies when I feel wronged, and sometimes they’re so over the top, they make me laugh out loud. Really, I’m a nutjob.

I love the piece “Because the Sign Was Missing,” which you note was inspired by a real-life garden. Can you talk about that inspiration a bit?

I had the great good fortune to tag along with a friend to a birthday party for someone I barely knew. The celebration took place at a large property on Lake Martin in central Alabama, owned by a man named Jim Scott, the father of the person whose birthday we were celebrating. Even with directions we had a hard time finding the place. We were driving around rural Alabama in the rain, and suddenly we started seeing the oddest signs, for the Gate of Felicity, the Gate of Humility, the Gate of Mirth and Sorrow. So we were intrigued even before we arrived.

Once we found our way inside, we encountered a singularly magical place, so beautiful and strange as to be nearly indescribable. The piece I wrote tried to capture its extraordinary qualities, the element of mystery and surprise as you wind your way through, the allure of its pathways, the feeling of being lost and found, over and over, the drama of the changing landscape, both wild and curated, the enjoyment of so many spots to stop and rest and dream. And the garden’s elemental playfulness, with its secret room behind a waterfall and its giant chess board and its lookouts and nooks—it’s a place that appeals to the innocent child inside us, the person who can take delight in the natural world and be led along by its wonders.

I'm curious, because I loved the book club questions so much! Who is your ideal reader—or rather, what is a way you wish your book to be read?

I don’t really have an ideal reader in mind. And I don’t have a particular way I wish the book would be encountered. Any reader who approaches it in a spirit of openness and curiosity—a sense of humor is also a plus—could potentially enjoy it. I think the book on the whole is approachable. The pieces are short and for the most part easy to understand. The language is direct, not too complicated or challenging.

I suppose I’d prefer it if people took their time reading. Though short, the pieces are quite intense, full of feeling. Every potion is its own small adventure. Each takes you to a place—sometimes a fairy tale or fable, sometimes a dreamscape, sometimes a surreal scene, sometimes an unlikely dialogue. I’d suggest immersing yourself for a spell, reading a few pieces at a time, just luxuriating in the words as they roll over you. When you have your fill, take a break, get a snack, go for a walk around the neighborhood with a friend. Then wade back into the book for a few more, back and forth, until you’re done.

Check out our other recent author interviews

Nirica Srinivasan is a writer and illustrator from India. She likes stories with ambiguous endings and unreliable narrators.

Did you like what you read here? Please support our aim of providing diverse, independent, and in-depth coverage of arts, culture, and activism.