Heide Hatry discusses ONLY AT DUSK: A TRIBUTE TO FLACO THE OWL

Flaco 2010–2024. New York, 2024. Assemblage incorporated into an excavated nineteenth-century book, with an Icons in Ash portrait made from the undigested bones of Flaco’s prey. 5.4 x 4.25 x 0.6.”

Ivy Brown Gallery is proud to present a solo exhibition by Heide Hatry, honoring Flaco—the Eurasian Eagle Owl whose bold escape and survival in New York captured the city’s imagination. As a fellow immigrant who arrived in America to pursue her artistic calling, Hatry found a deep personal connection with Flaco’s brief but poignant journey.

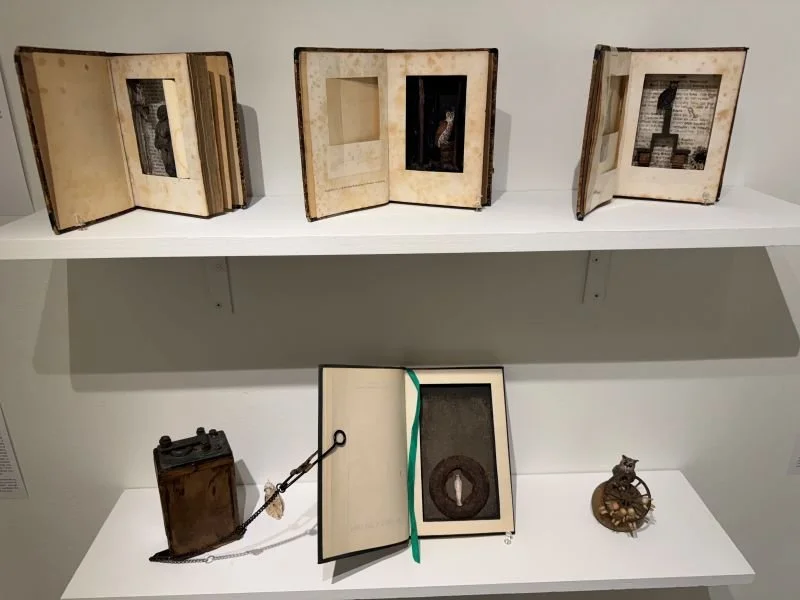

The show features unique book-based objects, assemblages, and artifacts inspired by Flaco. Many works incorporate owl pellets Hatry collected beneath his Central Park perch, forming a poetic, material bond between artist and bird. Some pieces appear in Flacofolio, a collaborative artist’s book with poet Leonard Schwartz (Spuyten Duyvil Press), while others are being exhibited for the first time.

Only at Dusk: A Tribute to Flaco the Owl is on view through August 7, by appointment only. Click here to contact the gallery.

Interview by Tyler Nesler

You’ve written that from the moment of Flaco’s “escape,” you were enthralled by his fortunes and took every chance you could to be in his presence. Why do you think you were so drawn to him? What are some aspects in the trajectory of your own life that mirror elements of Flaco’s existence?

The first impetus drawing me to Flaco was probably not much different than what so many others experienced: here was wild nature reasserting itself and somehow eluding the efforts of its evolutionary “betters” to contain it, then going on to live in the midst of the deeply alien human labyrinth, seeming at times even to preside over it in majestic serenity.

His freedom of flight, the confident self-sufficiency of the predator, his animal grandeur in the face of our dilute physicality; these and so much more, mostly unexpressed or inexpressible – perhaps even on that very account – amounted to something like a compulsion. As my life intermingled with his, as I made art for and about him, I began to see and think about myself in his terms – obviously, what I could imagine to be his terms. I could see the artist as predator, ever alert even when the dictates of her hunger are in abeyance, and how the basic and recurring fact and satisfaction of hunger constantly contributes to the creation of a new being, how what she cannot digest takes on form as well, how art is a response to what we cannot entirely assimilate, and, perhaps most importantly to me, the basic innocence and naturalness of this alimentary relationship: that all living things depend upon death for our survival, and for many of us, violence. But nature and peoples who have arrived at a respectful relationship with it offer a model of balance and wisdom that implicitly rebukes consumption-, profit-, and “growth”-based ways of life, and in becoming intimate with Flaco over the months of his liberty, I found myself pondering the dynamic of nature vis-à-vis human society along such lines.

As to my more autobiographical or personal identification with Flaco, I spent more than half of my life yearning to live as the artist that I am by nature and which circumstances, including the wishes of and pressures exerted by others as well as my own respect for the responsibilities I’d assumed and how all such things become internalized, contrived to prevent my doing. I could empathize with the years of silent, flightless, imposed captivity that denied him the pursuit of who he was “destined” to be. And I heard in his song the conflicted and always complicated celebration cum lament of the poet.

Display from Only at Dusk: A Flaco Memorial Exhibition

You began making art related to Flaco almost immediately from the time you started communing with him. Was this a spontaneous impulse? Do you think that you were compelled to do this as a way to better understand your personal fascination with him?

I’m afraid that I gave a misleading impression, which I can see is related to the human urge for coherence. I was obviously “collecting” experience and material for some future but as yet unknown art purpose throughout my relationship with Flaco, but I didn’t actually begin making the art until after his death, when all of that suddenly took on more powerful and urgent meaning. As if the stuff had, perhaps paradoxically, become animated by his death. In fact, as I look at the history of my life as an artist, it seems that the unifying factor is death: that my creativity is spurred, or triggered, by it, that, in spite of anything I’ve learned through my deep contemplative immersion in the “phenomenon,” I seem to be provoked, perhaps even offended by the finality of death, its denial of everything that life has taught us about ambiguity, uncertainty, liminality, interstitiality, continuity, toleration, perspective, compromise, multi-dimensionality, holism, phenomenality, dialectic, paradox, the “in-between,” and so forth.

But in spite of the groundwork I seemed to have been laying and my personal history as an artist, I still didn’t have any clear, analytic sense of why I was doing this. I still began the work from a perspective of ignorance. And to whatever extent possible, of openness. For me the act of creation always precedes its understanding and, in the work, asserts its priority over and perhaps even something like disdain for the latter, as endlessly provocative and compelling as I find the effort to achieve it. So, yes, it was far more spontaneous than pre-conceived or intentional. With distance, I can see that the way Flaco seemed so out of place and yet comfortable with that fact attracted me. And in my relationship to the work that our relationship engendered I see the same perplexity or urge to understand recapitulated, since I often don’t know what I was driving at in the individual objects, or even in the corpus as a whole. In the descriptions I prepared for the show I’ve offered any number of post-hoc speculative appraisals, which constitute, in part, a sort of auto-psychoanalysis, but I really see no end to that, nor do I feel that my own interpretive impulses have any greater standing than those of whomever else might think about them; if anything, perhaps lesser, even if they might suggest avenues for the canny unbiased analyst. Which doesn’t disconcert me, either, as I love the feeling of being at sea, of trying to get my bearings in strange waters or among alien ideas, and reckoning with what unexpectedly gets vomited up by the opaque requisites of my creative needs.

Flaco XII (The Burden of Conformity.) New York, 2024. Assemblage incorporated in an excavated early nineteenth-century book bound in half-calf and marbled paper-covered boards preserving a text fragment of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s Julie as background, and including carved bone Dia de los Muertos skulls behind glass and a paper cut-out of an owl. 5.5 x 3.6 x 1.”

You often found pellets embedding the bones of Flaco’s prey in a “cocoon” of feathers and pelt beneath Flaco’s favorite perches, and you used some of these undigested bones in a few of the works in this exhibit. What attracted you thematically and philosophically to featuring these bones?

Pretty much my entire opus addresses the waste-matter of the transit of humanity, the refuse, the dross, the negligible, the disdained, the discarded, the ruined, the decayed, the lost, the unconsidered, all of which constitutes something like the unconscious of capitalism, consumption, and the obvious fallacy of self-interest, which we are compelled to shroud in oblivion lest the guilt of it all destroy us…or worse, the system whose demands it serves. The bones and other undigestible residues of Flaco’s prey appeal to me as residues of lives whose ostensible purposes have been served and then forgotten about entirely, on the one hand occluded within these neat, practical, metabolic by-products, but on the other, seemingly gently ensconced in what might be seen as beautiful little organic tributes that the surviving life makes to those that sustained it. That may seem a bit airy-fairy, but along the lines of my sense of the predator in nature as being in sync with its prey and both of them part of a grander harmony that we humans have managed to put awry, its symbolic value, at least, is undeniable.

Psychopomp. New York, 2024. Assemblage incorporated into an excavated nineteenth-century book, with hand-colored paper cut-outs of a mummy and grave offerings and rusted circular object. 5.4 x 4.3 x 0.75.”

Many of your Flaco works are book-based assemblages. You were an antiquarian bookseller for twenty years in Heidelberg, Germany, and so books have significant meaning in your life. Can you discuss how your personal connection to books intersects with what Flaco meant to you?

Let me begin by saying that books were the key to my own freedom. I had no notion that they, well, other than the Bible, existed when I was a child and no real notion of what they contained or represented even into late adolescence. That said, it’s undeniable that close or intensive reading of even that one book can release the imagination and stimulate all manner of thought, interpretation, and inquiry. That I was a farmer’s child was probably helpful, too, because we’re compelled to recognize the limits and the truths of the world and don’t have the luxury of persisting in beliefs that have shown themselves to be fraudulent, inadequate, or even merely hopeful. Prayer might not make the crops grow, but God might actually seem to be helping those who help themselves.

At the same time, books transport us in space and time; one might go so far as to say liberate us from their grasp. And it is, accordingly, easy to lose oneself in worlds of the imagination and believe that they’re real, especially those of the more overtly sober-minded variety; one must read judiciously and critically, even while appreciating the freedom that books represent and exemplify. We must be wary of denying the truths of nature that books may easily seem to dissolve (which I can see might be read as exactly the opposite of what I mean here, though that in itself supports the point), or rather must understand that truths exist on a continuum and evolve as imagination is applied to the world.

For me, Flaco, like the book, means freedom and wisdom and their complicated dialectic, the implicate wisdom of nature (if I may invoke David Bohm). One might see the book as human nature and Flaco as “original” nature, although neither exists in “pure” form. In hollowing out the books I use as spaces in which to address my concerns and feelings about Flaco and what – the many things – he represents, I think I’m saying, on the one hand, that humanity must always be flexible enough to accommodate nature, indeed that nature is fundamental and must remain foremost in the sphere of human intentionality, that the latter must not insist upon its right in contradiction to it, in spite of what might seem to be the Biblical injunction to exploit the world for human purposes. But the medium as I’ve employed it might also be seen (even) more metaphorically as a process of digging into the book, of entering it and of conscientiously dismantling it by means of thought, of bringing one’s experience to bear upon it. The contents of these objects are frequently representations of lived experience that challenges the austere sanctity of the book, or thought, as it were, in the face of existential crisis that thought alone is insufficient to address, much less to resolve. They are in some respect crudely analogized depictions of the necessary integration of thought and practice in all genuine wisdom.

Schatten des Todes I. (In the Shadow of Death I.) New York, 2024. Sculptural assemblage with rusted metal plates and rag-paper figure. 5.3 x 4.1 x 1.1.”

Hegel’s dictum – “the owl of Minerva takes flight only at dusk” – inspired the title for this show. What did Hegel mean by this pronouncement, and how did this meaning directly inform your approach to creating these works?

It would be disingenuous to purport that the exhibition was conceived under the aegis of Hegel’s remark. The title rather manifested itself in light of the eventual character of the work, most or at least much of which had been completed prior to that moment. But the basic thrust of the exhibition, as it was of my understanding of Flaco’s life in the “wild” and of the way of the world in general is consonant with the traditional interpretation of Hegel’s point, namely, that wisdom arrives (if ever it does) only after the effects of the “sleep of reason” have become palpable, when it’s too late to make different decisions and the damage has been done.

I, however, prefer to take a slightly different (and not at all un-Hegelian) read on the matter. The owl awakens and takes flight at dusk in search of new sustenance, which for me suggests the quite natural and persistent renewal of hope in the very facts of need and desire. And, of course, to my mind, the predator in nature manifests the very essence of conscientious “exploitation,” which we humans must recover if we are to survive.

Flaco’s Ghost IV (The Owl of Minerva Takes Wing only at Dusk.) New York, 2024. Assemblage incorporated into an excavated early twentieth-century small octavo volume with “ghost-print” on acetate, paper cut-out of a parrot, and metal pocket-watch element. 6.5 x 4.4 x 0.9.”

The show features several “uninvited collaborations” that incorporate the work of other artists and recontextualize them in ways that relate to Flaco and his life. What was your process of selecting these works, and could you discuss one or two of them that especially resonate with you?

Although the intention remains the same, I’m still not totally satisfied with the “uninvited collaborations” descriptor. I thought of “empathic predations” the other day, but that, too, leaves something to be desired, if more on a linguistic than a conceptual level. It sounds a bit too intentional, and still violent, even if I was trying to subdue that tendency with “empathic.” I feel like more passive and osmotic processes like phagocytosis could be brought to bear, but I haven’t yet happened on just the right balance of subject and object. In a way, I also see it as related to what I said about death earlier. A lot of these works and objects, though I obviously had them for a reason, had become inert over years of living with them, and the empathic energy that communing with the spirit of Flaco generated suddenly reinvigorated them by encompassing them in my current passion.

In any event, I’m still meditating on a lot of this. The “collaborative” works I’ve invited to take part in the show are mostly things that took on this new life, as it were, without my conscious intervention. The Bill Sullivan painting of the East River cityscape and the e.e. cummings painting of lower Manhattan were things I saw every day in my studio, and it was only a spontaneous moment of empathic imagination that made me suddenly see them as perspectives from Flaco’s point of view, making me wonder what he would make of those vistas, how he’d perceive them differently than I do, whether they’d have aesthetic or “spiritual” dimensions for him, and whether or not that were the case, what would determine the “meaning” of a particular environment for him versus what determines it for a human. And, of course, to what extent would the larger, more obvious elements of the scene be relevant to him at all? The ink drawing of misty mountains is also something from my normal surroundings, but here I was not so much imagining his response to such a vista as fantasizing his joy, as it were, in a wild that was more genetically determined to suit him than that of Central Park.

Perhaps the “collaboration” that I found most beguiling (and distressing) is the Gordon Wagner abstraction that, completely against my will, kept revealing pareidolic images of owls from within what then appeared to be a densely clustered cityscape at night, reminding me, of course, of Flaco’s eventual fate.

And the completely inadvertent art object, the fashion designer Horst’s, riveting platform with its galaxy of “o”s formed by decades of hammering rivets into leather on it, gave me the sad and glorious impression of Flaco’s lonesome hooting into the night. In fact, quite a few of the texts and objects that I used seemed to reveal a preponderance of “o”s – if you listen to a recording of an Eagle-Owl’s calls, you’ll immediately see why I was attuned to such a “discovery" – and I drew this fact to the surface here and there.

Fana: The Infinite Return. New York, 2024. Assemblage incorporated into an excavated nineteenth-century book, with over-painted paper cut-out of an owl and metal spiral. 5.4 x 4.4 x 1.1.”

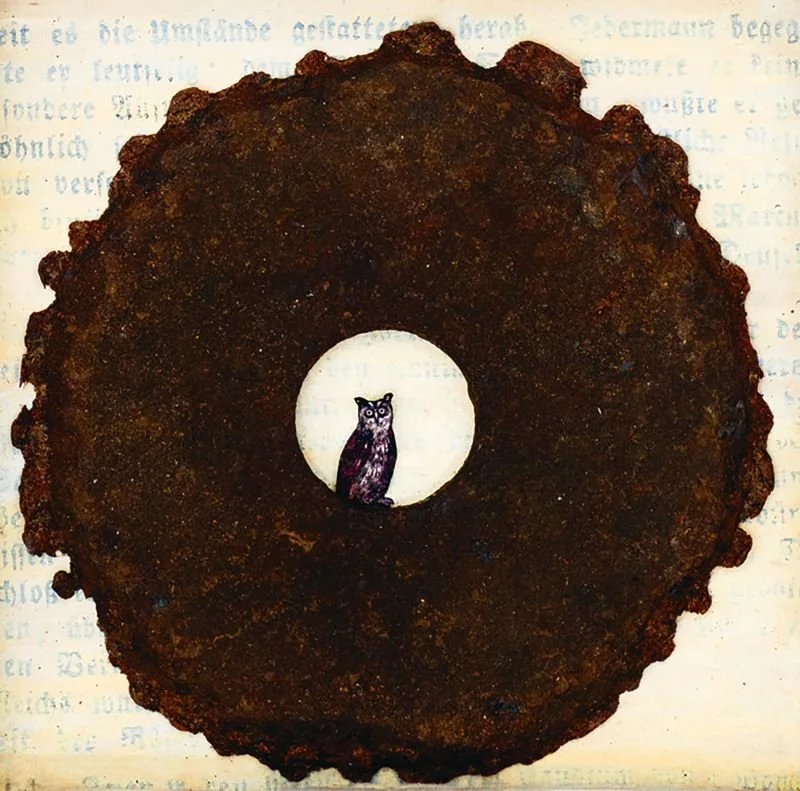

The Melancholy of Distance, the Echo of Solitude. New York, 2024. Assemblage incorporated into an excavated nineteenth-century book, with paper cut-out of an owl and rusted industrial object. 5.54 x 4.25 x 0.4.”

There are also assemblages not made from books but instead from a unique variety of other materials, some of which feature birdcages. How do these birdcages comment on Flaco’s status of freedom vs. captivity? Was he ever really “free,” even after his zoo escape?

It certainly didn’t start that way – like so many others, I wanted the illusion to be real – but ultimately the whole body of work explores the fact that freedom demands compromise even in the best of circumstances and that it is necessarily compromised by circumstances wherever it exists in any form at all. And this equally in nature (if it can be said to be “free”) as in the human environment.

Maybe Flaco experienced something like freedom precisely because he’d been subjected to the purposes and predations of humanity, and maybe that has something secret to do with why he was able to captivate such a large human audience. He was responding to the same things that oppress us and seeming, for a while, at least, to be prevailing…precisely by “returning” to nature. Which we, in turn, were doing vicariously through him. To return for a moment to the previous question, we were appropriating Flaco’s experience at least as an aesthetic, if perhaps not quite going so far as to make of it a moral protest.

In the Mountains of Madness. New York, 2024. Assemblage incorporated into an excavated nineteenth-century book, with painted paper cut-out of an owl and rusted objects against a background of Germanic Frakturschrift text. 5.4 x 4.4 x 1.3.”

Some of your works also appear in Flacofolio, a collaborative artist’s book with poet Leonard Schwartz. How did this collaboration with Schwartz come about, and did the process of working with him expand or enhance your own perceptions of Flaco in any unexpected ways?

Leonard and I have known each other for more than a decade and our creative lives have intertwined in a number of less explicit ways during that time, though we had wanted to find an art project on which to collaborate for quite a while. I showed him the first of the book-assemblages that I made, and he agreed immediately that this should be our collaboration. In fact, I modified the work to include a poem that he wrote in response to it. As I continued making work, I came across a book by Octavio Paz and Marie-José Tramini called Figures & Figurations and suggested that we might do a larger-scale collaboration along similar lines, which Leonard found appealing and which inspired him to write a far more meditative and broad-ranging text than we’d originally imagined, which in turn inspired me to make new work in a sort of dialogue with his.

Although I can’t recall the specific influences his text had on me – at this point I find it difficult to separate what I thought prior to our collaboration and what I eventually came to understand on the basis of it – we both definitely took inspiration from the other and grew into the project on that account, which for me is the ideal result of working with another artist. In a way, I feel like I’ve actually lived his experience during this process, which one might view as another form of the involuntary collaboration that haunts the project.

But I do remember an instance in which we were both affected by the insight of a third party. At a reading in Washington, a member of the audience likened Flaco’s history, on a number of registers, to that of enslaved and then freed Africans in a way that neither of us had previously considered and which is now inseparable from our thinking about it for both of us. Again, summoning thoughts of how the basic relationship to art is always a form of often involuntary and usually subliminal collaboration.

Only at Dusk: A Tribute to Flaco the Owl is on view through August 7, by appointment only. Click here to contact the gallery.

Did you like what you read here? Please support our aim of providing diverse, independent, and in-depth coverage of arts, culture, and activism.

Tyler Nesler is a New York City-based writer and the Founder and Editorial Director of INTERLOCUTOR Magazine.