The roles of language in ritual & tradition: Anne Waldman on her new book MESOPOTOPIA

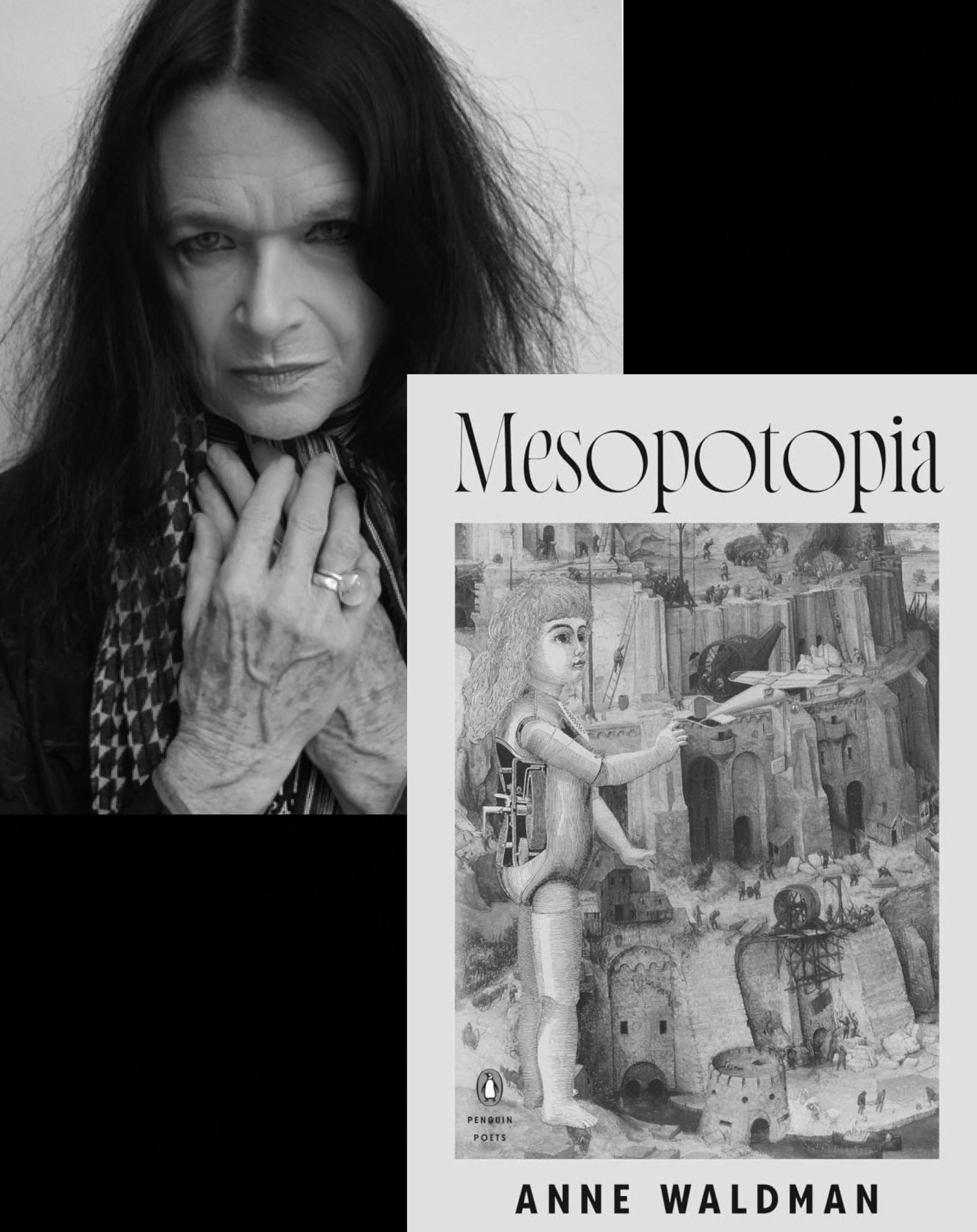

Photo by Shannon Sky

Poet, professor, performer, librettist and cultural activist Anne Waldman is the author, most recently of Mesopotopia, (Penguin, 2025), and Archivist Scissors (Staircase Books, 2025). The Grammy-nominated opera / movie Black Lodge, with music by composer David T. Little, premiered at Opera Philadelphia in October 2022.

She is a co-editor with Emma Gomis of New Weathers: Poetics from the Naropa Archive (Nightboat, 2022). Her newest album is “Your Devotee in Rags” from Siren Recordings in Toronto with composer Andrew Whiteman. She is one of the founders and a former Director of The Poetry Project at St. Mark's Church In-the-Bowery and a founder of the Kerouac School at Naropa University in Boulder, CO, where she is the Artistic Director of the annual Summer Writing Program. This summer’s theme (June 2026) is “Metabollic Thrum".

The film about Anne Waldman, OUTRIDER, directed by Alystyre Julian, and produced by Tamaas Foundation, and executive producer Martin Scorsese, premiered at Anthology Film Archive in April 2025 and is traveling the world.

Interview by Isabelle Sakelaris

Some of your poems use accumulation—visually, and through litany, such as in “Herminuisance: Mesopotopia the Intro.” What is it about litany or accumulation that felt especially useful or poignant for this book?

“Herminuisance” is meant humorously. Hermeneutics engages interpretation of the literary, of the Biblical. “Interpret words in harmony with the author’s time.”

This is one of the most complicated times to speak of harmony. Hard to put aside, ignore. Trying to make an inventory of experience, consciousness, impressions, struggles, emotions, loss of reason, ethical and moral calamity to make sense of this time. How it arrives I think is a karmic accumulation and in some chronicles we are inside the early speeding stage of the Sixth Extinction, Endtime, Kali Yuga. On every level, scientific, philosophical, spiritual, racial, we are in a time of ongoing stress, reckoning and crisis as more citizens too are murdered in the streets of the USA, as at Kent State—exercising their right to assembly, to protest, to disagree, taking for granted the freedoms fought for in an imperfect world. It’s been going on since the 60s, demonizing people, labeling them as commies, terrorists, aliens, political assassins. And all this is being stoked.

Other places are worse, as we know from ancient and recent history. The endless wars. The stories of empire. The contrast to the naked “bare” body of homeless, migrants, crises of weather and war closer to home now, horrors orchestrated by the robber barons and oligarchs. But the blatant current war in the streets from ICE raids in the US is exceedingly dangerous and intentional. Driven by a white supremacy obsession and a power grab. We are surely on a fascist verge with a blueprint for absolute tyranny. We haven’t been vigilant as we should be, taking freedoms for granted that we thought we had at least started to secure in the 60s, etc. But never enough: identity, race, sexual orientation. My Black friends see it all quite differently. They have lived with trauma and genocide their whole lives through many erased histories. There is also a level of deep ignorance upon the land as we cede to the divisive powerful AI robotic algorithm. Corporate entities running your complex life, your existence? Our epic life is everywhere around us, quaking. So this was the inspiration. A kind of dense alarm of language and visuals and music in a book.

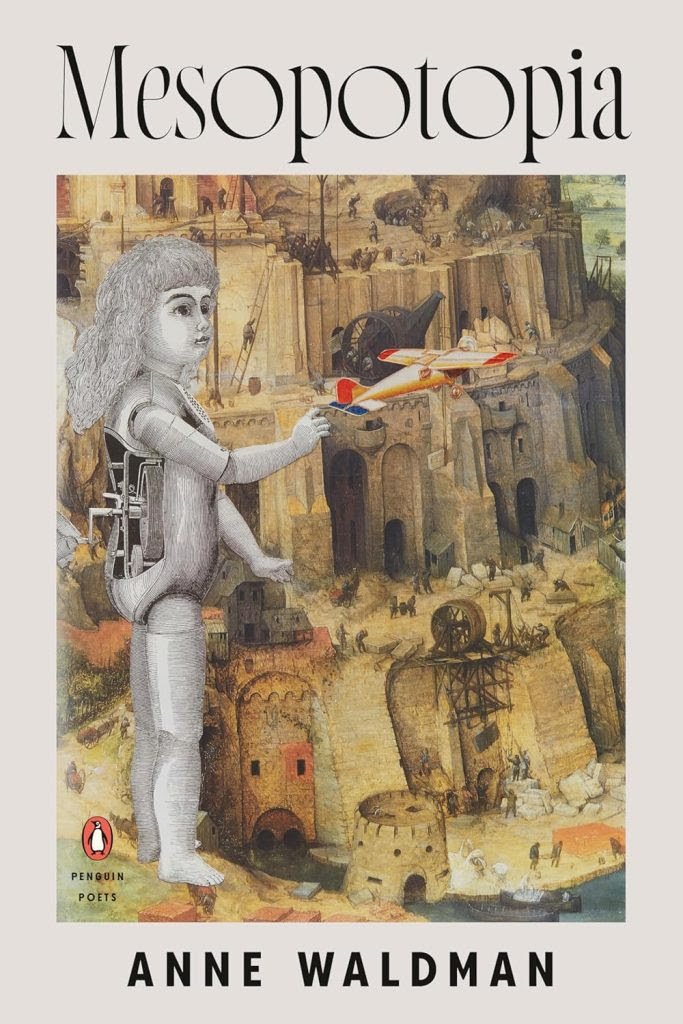

A tall order for a book of poetry I had envisioned for quite a while, feeling the urgency of completing it during the time frame of 2025. A guiding image was a collage by poet John Ashbery, which is on the cover of Mesopotopia. A young wind-up doll standing in front of the Tower of Babel, sending a toy airplane into the void.

Thus, Mesopotopia was a way to cope and expand and release my burning cri de coeur. I wanted a “hinged" open form, with seven sections (staves) but carefully edited and arranged as ballast to Project 2025 and its agenda of undoing just about everything. Flipping the infrastructures, closing down scientific and literary institutions, research, and support, making us less safe. I was haunted by all the ramifications. The death of civilization was conjured in the larger worldly and astral omens and poetic-mind cosmos.

Litany is heartbeat, litany is the relative world clock. Litany is a pile of rubble, a treasure of precious gems. A tangle of language and citation. Many voices through time and space. It is also a performance of resistance, as I wrote it, experienced it. I was also going through difficulty and care of my partner, the brilliant filmmaker and collaborator Ed Bowes. And I studied what he might be undergoing with some memory loss and responded with a more sensory, telepathic communication though poetry:

without light

counting heavenly

bodies on hands, vehicles of motion, our hands trembled

in our head, reading dust particles as talisman

were we sick? (“Avicennan Medicine” MESOPOTOPIA)

In the mind of the poet, all times are simultaneous and mysterious, a Modernist adage. Imagination travels, revisits, ritualizes, recreates, recombines. Poets are also acolytes of existence, of the dark and critical history of our Time. The Anthropocene. We are epic chroniclers, more barriers are down, erasures. Still playful, though. We need to recover archives. The cancelling of peoples. Our emotional memory or factual memory of them. I have written a larger epic of over a thousand pages, which you mention: The Iovis Trilogy, Colors in the Mechanism of Concealment. A longer ride. Addressing patriarchy. Written over a decade. Certain themes and procedures continue as works of montage, ritual, performance, and history.

Many of your poems take up and rehearse rituals (from many different traditions), such as “To Take the Measure (Barometer),” in which the speaker describes the canonical hours. Why do you think ritual is important? Is the act of writing poetry similar to a ritual for you?

Indeed, it may be. It is basically an act of meditation. Also mediation. Also in media res. Epic is not necessarily chronological.

For me, epic and these longer screeds are a naming, a reminder, a calling out, for luminosity, for insight, for intelligence, for poetry that we may have extraordinary music all over the world, and hail poetry as possibly the oldest religion. We create calendars to follow the seasons, our own natural life cycles. I included in Mesopotopia a random litany of 365 lines for each day of a year. We ritualize and count to keep it all spinning, to honor the fallen, welcome the newborn, reenacted daily with the lunar and solar cycles. Emptying out, seeing life as impermanent. Living and dying moment to moment. Beautiful, shimmering, extraordinary. The features of our landscape, the ongoing improvisation and accidents and of the entanglement of natural forces and all the incredible species for billions of gestating years. What comes up as the thousands of fleeting “things” in this world and how we have named, celebrated them. Where we have very attuned evolved sense perceptions to acknowledge the zeitgeist, dance with it. Challenge it. We also have the dark side, human greed and atavism that wants to hold on to power, to the material stuff, create weapons of mass destruction with the threat to annihilate. We are insane with power and ego. I am drawn to the litany of ritual through many traditions, as you say, poems that honor the times of day. Confessions, pyramid texts, lullabies, dawn songs, Buddhist chant and sadhanas, Old Testament Isaiah, mystical poems of Hafiz, and so on. These seem to attend my life.

You make many references to music and sound throughout Mesopotopia, for example, using the word “stave” (which is the five lines and spaces between, where music is written in a score) and in some titles. You’ve been associated with the Beat poets, you’ve collaborated with the Fast Speaking Music label, and have written libretto in the past. What do you think is the relationship between music and poetry? What is your approach to bringing out the musicality of language?

Yes, I wanted to invoke a musical association. Classical music leaves one’s imagination more liberated in space, words can tie it down. I often refer to the larynx as the instrument of poets. I often hear the music in words first before the etymology, in the phones and phonemes of words. But I want to mention that “staves” are also vertical posts or planks in buildings. Staves accompany the Ark of the Covenant. They represent divine authority and also are the “rod” and “staff” of shepherds. This is a motif in the recent film Outrider (Bio of AW). The outrider rides alongside of, a kind of guide. It’s a sheep herder term. Not an outsider.

But I wanted to make sure this epic-in-parts was heard. The words are always important. Linguistically sonic. We did (a 5-hour tape) reading for the Audible oral version, which included some musicians at certain points. With wonderful engineers. The jazz player Daniel Carter, musicians from my family band Fast Speaking Music, Devin Brahja Waldman on sax, Georgia Wartel Collins on double bass, and also her father Jonny visiting from Sweden. Patti Smith’s daughter Jesse Paris Smith working with gongs and a cellist, Arab song by Safira Berrada, and so on.

You mention the Beats who were explosive writers, preeminent seekers, and outriders. Explored fellaheen below-the-border worlds. Allen Ginsberg, Burroughs, and Kerouac understood the spiritual authority of Black music, bop prosody, blues, hymn, dirge. And they intervened in US and world culture at a critical time. Broke the hold of the left hand margin in poetry. Brought it into the public space, raised the ante. Allen stood up for tolerance and First Amendment rights, freedom of speech. I wrote a poem collaged into libretto for the opera Black Lodge with the composer David T. Little. Based in part on details of the complicated life of William S. Burroughs. It was produced by Opera Philadelphia, and is also an investigatory film featuring a solo virtuoso singer Timur. There’s a recording of Black Lodge which was Grammy-nominated. I was surprised. The music is quite powerful. It was such an odd atypical libretto. More like a poem. Also referencing Antonin Artaud in places.

But I also was making my own way, much in this musical approach in my young life with inclinations toward “sprechstimme”, with a small bit of training in Indian singing with LaMonte Young, then playing gamelan. Many unexpected, not always planned collaborations with musicians. Where the joy is listening to one another from different perspectives, registers. It’s a conversation with time and phrasing and pause. In my childhood, I sang Christmas carols in parks and banks and hospitals. I felt I was able to stand up and be capable in several spheres. It’s not that the music has to underscore the words, but they have mutual trajectories that complement one another. And can also be dissonant and unpredictable. I traveled with Bob Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue Tour, where I had my own responses to the gestalt with an 11-page poem, “Shaman Hisses You Slide Back Into The Night”. The concerts were electrifying. David, the composer, scored the text for Black Lodge. I participated as he tried some of the settings out, but he had the original idea for the opera.

In the age of the “attention economy,” your long poems are notable. But you’ve been writing long—even epic—poems, such as The Iovis Trilogy, for some time. Would you please expand on why you think long-form poetry is important, especially right now?

I often fret that certain poetries and spiritual traditions might become endangered. I want them to occupy a strong space, hold their own ground (book burnings in Texas!) I want to write inside and of the times for the “tribe”, my family, for children, tell some of the chronologies, their magic and stories of the endangered manatee, for example, as I did in Manatee/Humanity, a piece performed publicly with my son Ambrose Bye, with electronic and other sounds, including the voice of the manatee. I also worked with the cellist Ha-Yang Kim on this project. I think some of the striking parts in Iovis are inspired by modernist H.D., who left America and wrote her war trilogy in London during the bombings. Also, I tried to evoke from time spent in Indonesia, in India, in Vietnam, a quarter century after the American War. Sites of constant evolution, gnosis, and still conducting seasonal rituals and ancient traditions. But maybe I explain too much.

Fast Speaking Woman and the publication of the City Lights book (Fast Speaking Woman & Other Chants) after Lawrence Ferlinghetti heard the poem at a Buddhist benefit reading in San Francisco helped. Early 1970s. This was an anaphoric poem deeply indebted to the Mazatec curandera Maria Sabina. Gaining confidence of being wedded to poetry. I was also a student of and early practitioner of Tibetan Buddhism, and traveled to India for further teaching. Later wrote Structure of The World Compared to A Bubble, which was a long poem meditation during a pilgrimage to Borobudur on Java’s Kedu plain. I had felt the pull of the longer epikos by the 80s.

You’ve been called an “open field investigator of consciousness.” Would you please tell us more about investigation as a poetic practice?

Note taking, looking things up (not written by AI), conversation, study, research, books. “istorin” is the root of the word “history”: to find out for oneself. Asking questions. Poetic lineage of attention to the quotidian and vision, both. What torments one in the middle of the night! Find the original language. Etymologies, paying attention to natural rhythms, sense perceptions. Phrasing, internal rhyme, prosody. With the books just mentioned: observing the patterns of the swimming manatee, one example. How to echo that in language. The word comes from the word “breast,” manati, Caribbean. Also manito, according to an etymology dictionary, is "spirit, object of religious awe or reverence, deity, supernatural being," 1690s, from a word found throughout the Algonquian languages. As for the manatee investigation, I visited the “Museum of Skeletons” in Paris, and the manatee skeleton is situated next to an elephant skeleton, related to the elephant brain and consciousness, in both memory and empathy. The call to the Mahayana Buddhist Stupa Borobudur was a pilgrimage, a walking meditation of circumambulation, climbing up through passageways of Buddhist painted sutras on the walls to the magnificent top with its empty Buddha cage and stunning view.

For me, some of the investigative work seemed tied to shifts in tone and form throughout the poems (including within single poems), as if a train of thought were interrupted, or the speaker had a realization or epiphany. How does using form help you build generative poetic landscapes?

I sometimes have an anthropological urge to study origins, sites of artistic power involving sacred text and ritual, depiction of forms, structures, poetry transmitting threads of thought, philosophical, and religious that were interrupted, effaced, or destroyed. Borobudur was buried and not restored finally until 1983. The site and stupa itself were generative for the text. I wanted to cover many forms of the middle way, the Bodhisattva path of dharma. The 12 Bhumis, like stations of the cross or something. Steps on the way to knowledge are described in poetry form, interlaced with my own interpretation. There are constant interruptions for us simple scholars to pause and notate.

But that’s a wonderful comment. I interrupt myself all the time. Reading books simultaneously, stop and take a note, look at something, it’s the tentacular aspiration. What’s aside or astride the improvisation. The book’s “stave” structure holds all the asides, the other characters, moods, setting, angles, details of a salient dream. Other languages, even. Or the footnotes want to appear in the poem. How to make that work? But there is often a connection of multiplicity. What is hidden, what is revealed. Operas and plays often orchestrate several voices at once, some hiding behind a tree or in a boudoir. There is some of that in Shakespeare’s “Troilus and Cressida.” Another long poem-book, Voice’s Daughter of a Heart Yet To Be Born, inspired by William Blake’s Book of Thel, is divided into 2 sections: Innocence and Experience. Myriad voices. Not always agreeing. I kidnap Thel from Innocence and land her in the world of experience.

How has your work changed over the course of your career? What have you learned, and what do you want to try next?

Poetry was never a choice exactly. It was what I was most interested in. It changed quite a bit over the years. The early years at St. Marks were dominated by the second generation of New York School with the encouraging energy of Ted Berrigan for many younger poets. Bernadette Mayer had a terrific workshop that included a weekend of “dreaming the end of war.” My book Journals and Dreams was a departure as it included longer pieces. Looking back, I went from being a curious young seeker, a young performer growing up in Greenwich Village, exposed to folk music and jazz, classical music, and early literature studies. A home with books.

And now, the 21st Century, that is still what I am most interested in. A home with books. With friends, collaborators. And I care so much about the poetry communities and am still engaged with those and the Summer Writing Program at Naropa, and am working on a number of new projects with all of that same curiosity and entanglement. I learned how important incubation is for the poetry, the writing, gestation, letting the “themes,” for want of a better word, take hold, settle. Keep studying, reading, research if relevant. Take a walk in the woods, or in a park if you can before a writing session. Look up at the sky in the middle of the night. The partial moon, quite gorgeous right now, helps place and pace one’s heart and sanity.

Growing up in a bohemian household helped, but feeling also part of a golden age of experimental, radical “wild mind” art practices emanating out of NYC and beyond, that supported all of us. Especially in the amazing generation of such artists, musicians, and performers, dancers, and pioneers: Joan Jonas, Meredith Monk, Patti Smith, Laurie Anderson. To name some of the women. Also, I was deeply devoted to creating spaces for the work through The Poetry Project at St. Mark's Church In-the-Bowery and Naropa. There were never just “jobs”. Even as we protested the Vietnam War and every act of belligerent aggression since, we kept the work of poetry front and center, and are still going with small press publishing, archival practices, discourse of pedagogies, some of us teaching and lecturing around the world. Work is ongoing within these communities. We read poets of the past we love and those who have recently passed. Pierre Joris, Alice Notley, Fanny Howe. We honor them, as we also honor poets of many cultures, and that is a richness of this time in poetry. That extraordinary reach across all the difficult suffering and precarity towards translation heart connection. On my shelf is poetry from Turkey, Iran, Palestine, Greece, Mexico, Ukraine. By poets across many “wounded galaxies”. All poets I salute now as brave angels of the storm.

And what now and next? A short Buddhist memoir: “Dharma Gaze” is in the works. But I also have something tentatively entitled “Out of the Elucidarium.” Revisiting the Renaissance right now. But a less wordy structure I hope. Under 100 pages. Skinny lines. Maybe more like a conversation, give and take. Waiting for the omens. I'm working on a collaboration with the painter Pat Steir entitled “All That Surrounds.”

I worked with poet and artist No Land recently on an art and poetry book, The Velvet Wire (Granary Books), and on what will be a traveling exhibit with her as well: “Mercy-Eyed Down The Triple Highway,” with performances at Poets House in NYC. I also have a text with Zoe Brezsny, Wives of The Bath, coming out from Staircase Books (Cambridge) this year. Another recent recording: “Your Devotee in Rags” is now out from Siren in Toronto, with former Broken Social Scene genius Andrew Whiteman, based on The Iovis Trilogy. I’m working to place the brilliant Audio/Visual Archive from The Jack Kerouac School at Naropa University after 50 years. It’s a time of sanctuary, of care, archive, shelter, environment, and continuity of poems for the children of the future.

I went down to the boat of the evening…

(from “Pyramid Text”, MESOPOTOPIA)

Works Cited in this Interview

The Iovis Trilogy by Anne Waldman (Coffee House Press )

OUTRIDER by Alystyre Julian

Mesopotopia by Anne Waldman on Audible

Manatee/Humanity by Anne Waldman (Penguin)

Fast Speaking Music by Anne Waldman (City Lights)

Structure of the World Compared to A Bubble by Anne Waldman (Penguin)

Book of Thel by William Blake

Voices’ Daughter of a Heart Yet To Be Born by Anne Waldman (Coffee House Press)

Jack Kerouac School Summer Writing Program 2026 Naropa University

Check out our other recent author interviews

Isabelle Sakelaris is an art writer and aspiring poet who lives and works in New York City.

Did you like what you read here? Please support our aim of providing diverse, independent, and in-depth coverage of arts, culture, and activism.